Incan Tilcara

Visit Tilcara for an Inca fortress, good food, plenty of lodging options and easy transportation.

The town is very walkable and on almost every block I passes several small, family-run hostels and B&Bs. Between the center of town and the main tourist attractions are also a few campgrounds. I saw almost as many restaurants, but only had time to try one, which I thoroughly enjoyed. (Restaurant review is at the end of this blog).

Tilcara is one of the main towns in the Quebrada de Humahuaca, a valley that runs north and south between the high altitude altiplano on the west and the valleys that lead to the Amazon Basin on the east. The location made it an important trading center for the salt and other minerals from the altiplano and the food produced in the east.

The main tourist attractions are the Inca archeological site, the Tilcara Pucará and the adjacent botanical gardens. I also visited the archeological museum on the town plaza, which made me feel like I was back in Peru for its Andean exhibits and thoroughly Inca context, from coca leaves as offerings to the Pachamama to references of the region being part of Collasuyo.

I updated the Rough Guide to Argentina and am so happy how it turned out! Get 30% off the Rough Guide to Argentina with my author code AUTHOR0018 in their online store.

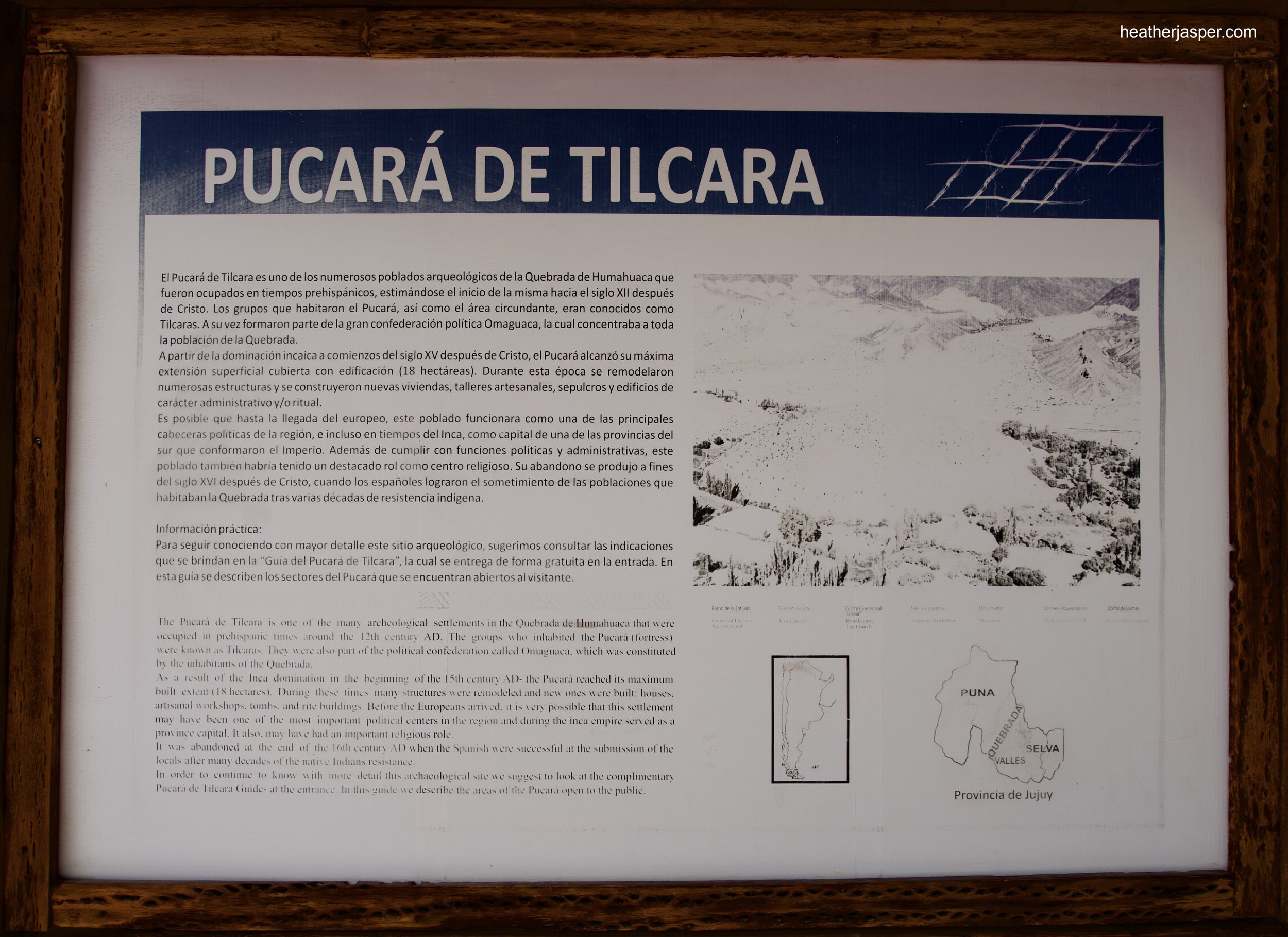

As a former center of Inca administration, Tilcara is an important stop on northern Argentina’s tourist trail. It showed me the region’s Andean culture even more than Purmamarca. The fortress is referred to by its Quechua name “pucará,” which in Peru is written as “pukará.” Unlike other pukarás, Tilcara didn’t have any defensive constructions, showing it was more of an administrative center than a military one.

Tilcara was a major stopping point on the Qhapaq Ñan, the system of trails and roads that linked Tahuantinsuyo. (The most famous part of the Qhapaq Ñan is the 4-day Inka Trail trek that leads to Machu Picchu). Archeologists have also found objects in Tilcara that show it was a trading center over a thousand years before the Inca began their expansion.

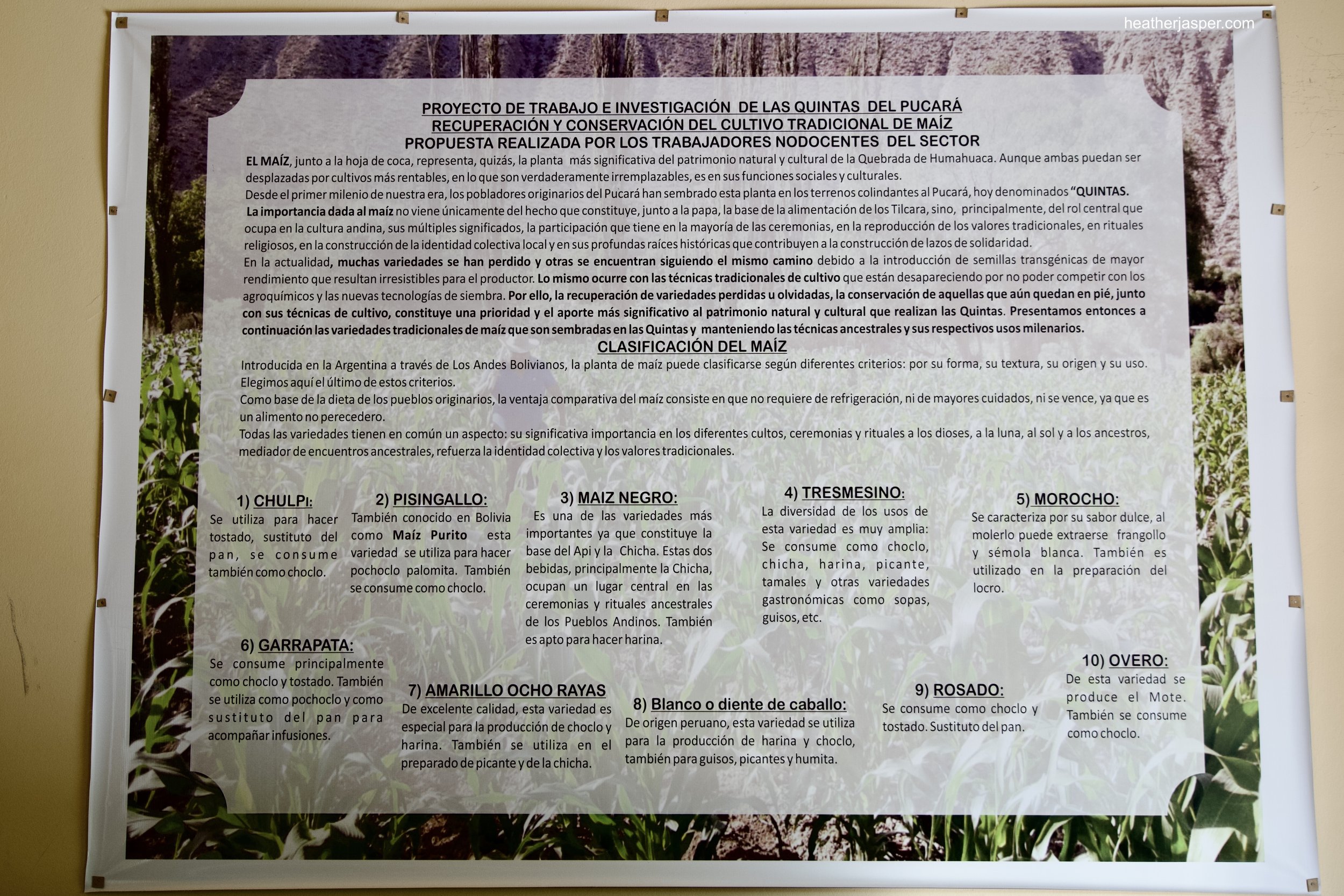

The most important trade products produced by the Tilcara people were metal objects, using the minerals in the surrounding hills. Nearby deposits of onyx, obsidian and marble created a trade in stone tools. Archeologists have found over fifty metal and stone workshops. The Tilcara people paid “mita” to the Inca with their metal and stone objects. They were also required to pay “mitimaes,” which was physical labor. This could be in the form of maintenance on the Qhapaq Ñan, working the fields that produced food for the Inca administrators or any other work needed by the Inca.

Conquered lands

The Inca tribute, or tax, system was the same throughout South America. Just as villages in Peru paid tribute to the Inca in Cusco, villages in Argentina sent the best of their products to the Inca.

The valleys produced corn, chili peppers and potatoes, Andean crops that linked the Tilcara people with the distant Inca. Cusco is about 820 miles away, as the crow flies. Between the two cities is almost entirely altiplano desert, high altitude salt flats and places that can support very little human life.

There are three layers of history that fascinated me at Tilcara. The most obvious was how the site was used as an Inca stronghold in the 1400s, in a region so very far from the capital of Cusco. The Tilcara people had only been part of Tahuantinsuyo for about a hundred years before the Spanish invaded South America, making them an easy target for the “divide and conquer” strategy.

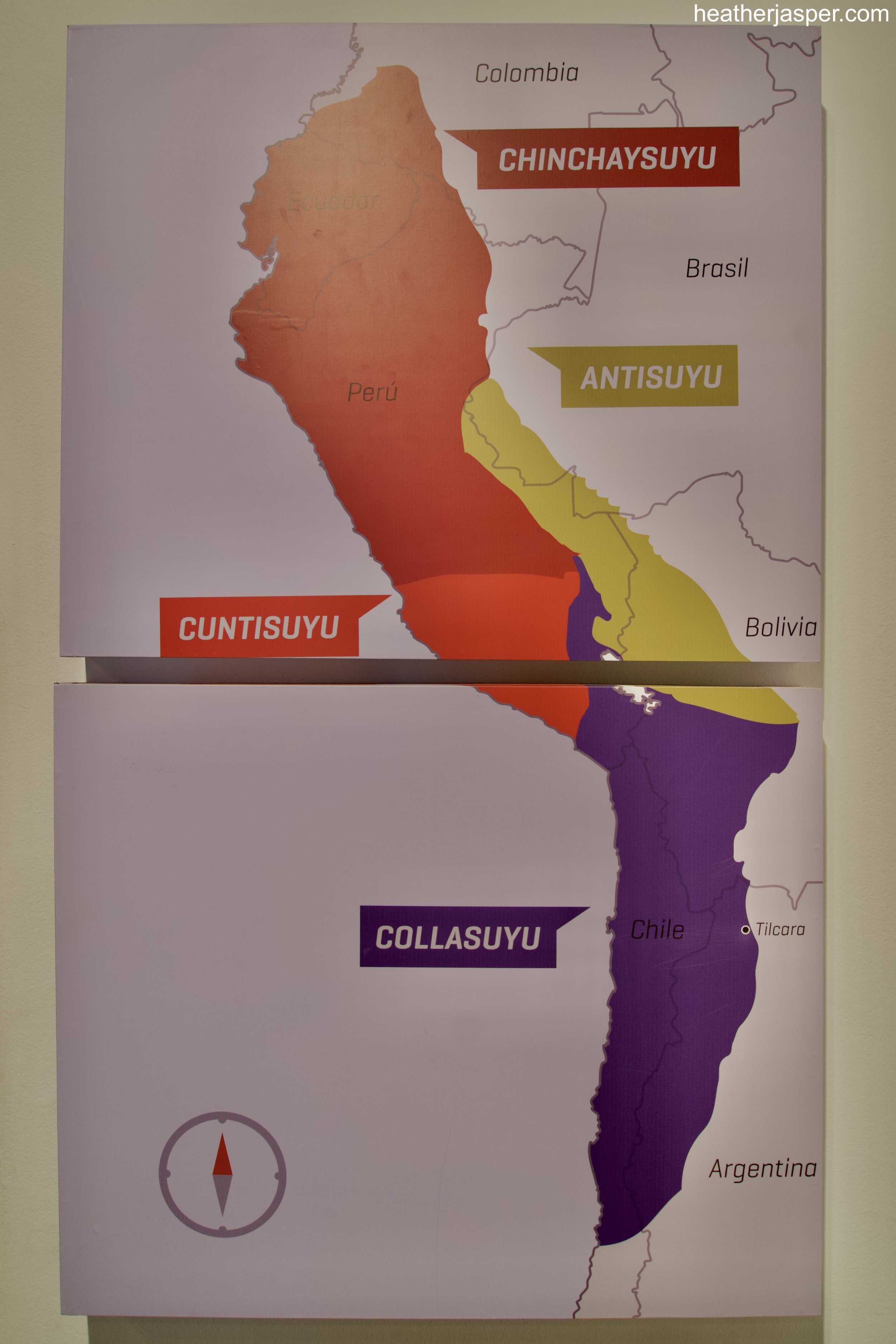

Map of Tahuantinsuyo

You see maps like this all over Peru, showing the former Tahuantinsuyo, which means “four corners” in Quechua. The name encompasses the four parts of the land controlled by the Inca, as shown in the map. Tilacara, like all of Incan Chile and Argentina, is part of Collasuyo.

Suyo is just as often spelled suyu, in Argentina and in Peru. The European alphabet doesn’t have all of the sounds in the Quecha language, so spelling is approximate at best.

Cactus construction

I was fascinated by the use of cactus trunks, which are more of a skeleton of dead and dried cactus. In a region with very few trees, cactus skeletons were used in constructions like this.

In the early 1900s, North American and European interest in archeology in South America brought another layer of history to Tilcara. After National Geographic published Hiram Bingham’s photos of Machu Picchu in April 1913, the archeological invasion intensified. The monument at Tilcara was built in 1935, with a puzzling pyramid shape. According to the plaque near the monument:

“This monument was built in 1935 to honor the archeologists Juan B. Ambrosetti and Salvador Debenedetti, who had researched the Pucará from 1908 to 1930. According to records, this area was the site of the last occupations from the Inca Period. The monument was designed by Martín Noel, who represented a generation of intellectuals that sought to create a national artistic style combining pre-Hispanic elements with European ones. The pyramid shows evidence of Teotihuacan, Maya and Inca inspiration, which were considered by those intellectuals to be the most advanced civilizations of Pre-Columbian America. However, these elements are not related to the architectural traditions of the Quebrada of Humahuaca.”

Monument to archeologists

The doorways seem quite Inca to me, but the pyramid shape mystified me until I read the disclaimer (above) about the design’s Maya influence.

This memorial at the Tilcara Pucará commemorates the victims of state violence from 1976-1983 and the Indigenous genocide victims since 1492.

The Argentine and Indigenous flags flank another monument to much more recent history:

“Memory, Truth & Justice

-More than 420 students, teachers and non-teachers arrested-disappeared from the Philosophy Department of the University of Buenos Aires

-More than 200 arrested-disappeared from the province of Jujuy

-More than 30,000 arrested-disappeared from the Argentine Republic during the State Terrorism of 1976-1983

-For the Indigenous Peoples victims of genocide since 1492”

I couldn’t find anybody who spoke Quechua as their first language, but I definitely found Quechua place names and Andean foods.

I was happy to find Restaurante El Puente, with Andean food like llama meat and quinoa. The Spanish who colonized the area brought a lot of goats, resulting in a continued tradition of local goat cheese production. While I can find quinoa everywhere in Peru, it’s much harder to find good goat cheese.

The service, food, wifi and shady garden were all excellent at El Puente. If you’re in Tilcara, the restaurant is near the bridge (Puente, in Spanish) near the pucará. If you head uphill from the plaza towards the archeological site, the restaurant is on your left just before the bridge.

How to get there?

Right on the main road from Bolivia to the cities of San Salvador de Jujuy and Salta, there are dozens of busses that pass through Tilcara every day.