Having Covid in Cusco

After writing for almost a year about other people having Covid, I now have the opportunity to give a first person account of having Covid in Cusco. Thankfully, I had a very mild case. I had a fever for two days and a slight cough the third day after the fever was gone. Unfortunately, the person who brought it to my home was so sick that I had to play nurse for about a week, before a family member could come get him. I’ve done the contact tracing, which goes from my houseguest-turned-patient to his family, who live in a small town in the Sacred Valley.

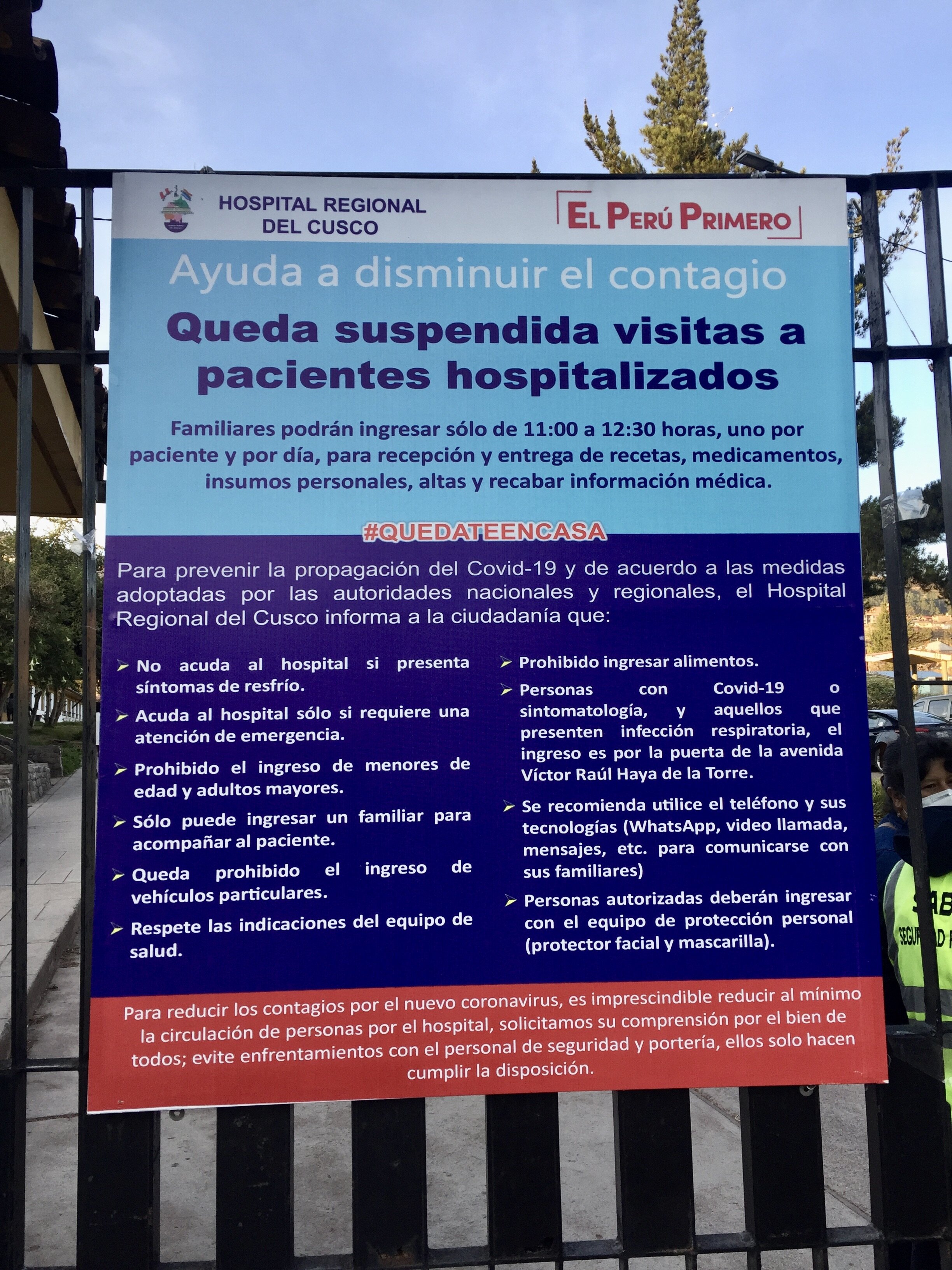

When I first realized that this was probably Covid, I found a list online of places in Cusco that supposedly can test for Covid. Of the 57 places listed, I called about a dozen, of which only two could do a rapid test. None of the ones I called could do the more thorough, and more accurate, molecular test. My first test came back negative, though the clinic told me to come back in a week to do the test again, since it has a high rate of false negatives. A week later I tested positive for both the IgM and IgG antibodies.

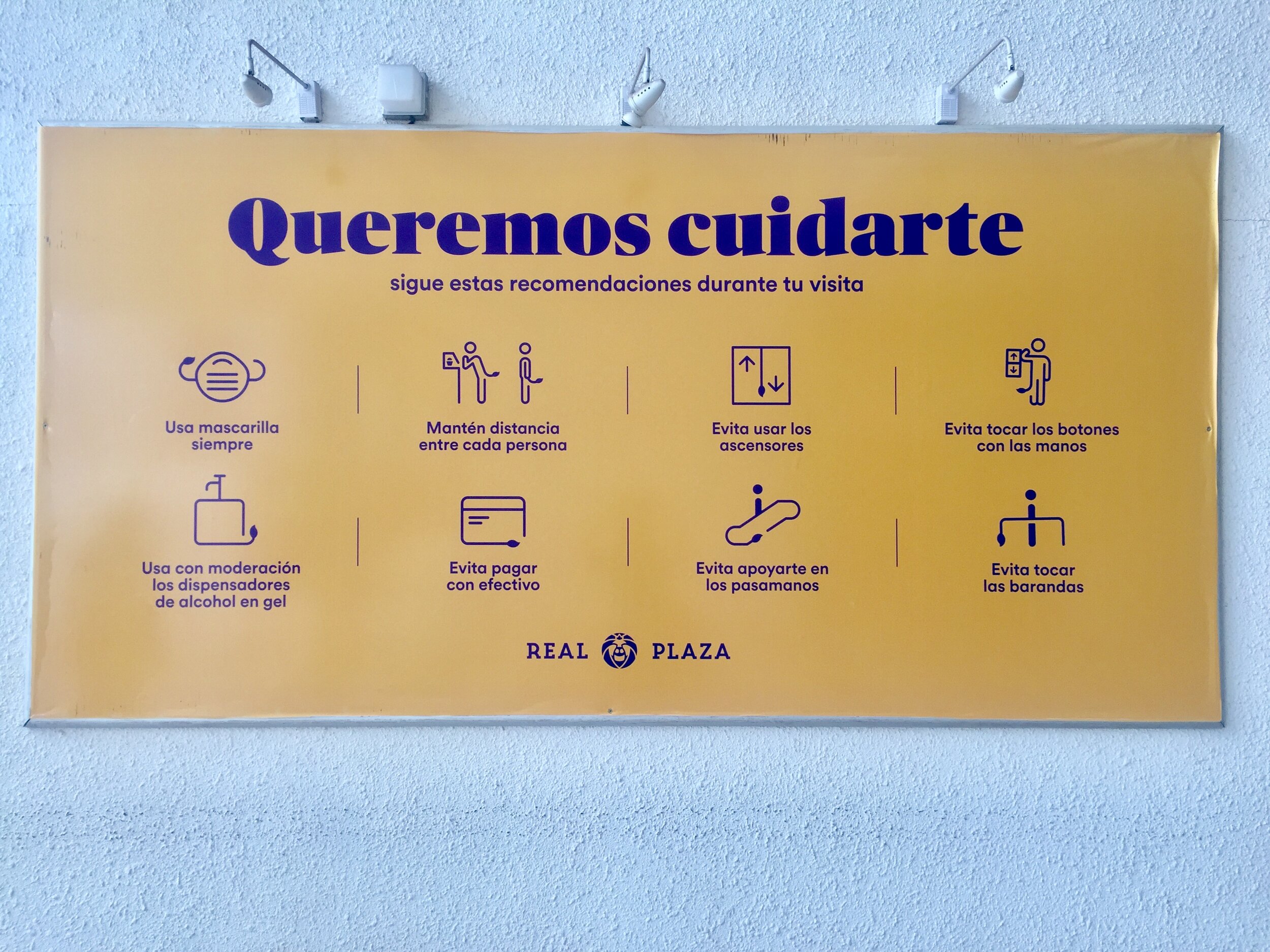

The body first produces the IgM antibodies, as an early immune system response to an infection. The clinic technician explained that the presence of IgM mean that the infection is ongoing and that I am still contagious. The IgG antibodies take longer to form and provide a longer lasting protection against the infection. I was told to come back for a third test, in another week, to check if I still have IgM antibodies. Until then, I should consider myself highly contagious and must stay home. The streets are not patrolled by military and police like they were back in April and May, but some police are assigned to enforce mandatory quarantines.

The positive Covid test brought a lot more paperwork than the previous negative test. All of a sudden, the technicians were very interested in knowing exactly where I live, asking for descriptions of the house on top of the actual address. They also had to fill out a form for contact tracing. I was asked if I had had any contact with somebody with Covid and who they were. I gave the names of my houseguest and his sister, the healthcare worker who was the first person in their family house to get sick. I was surprised that I wasn’t asked for their addresses or phone numbers, or any way to get in contact with them. Instead, I was instructed to ask them to get another Covid test. I was also told to contact Diresa, the Dirección Regional de Salud, and report myself.

Each Covid test cost me s/100, which is less than $30, but that’s a lot for most people here. That can be food for a whole week for a family of five in the city, or a month’s budget for a family in the countryside. Calling around to testing centers, most charged more than s/100. So far, I’m in for s/200, plus everything I’ve spent on cough syrup, cough drops and ibuprofen for the fever and headaches. Few Cusqueñans would pay another s/100 to be told that I’m not contagious anymore. While the French woman has been documented, the other two people I got this from have not had a positive test. By that logic, the number of people with Covid in Cusco is probably double the official numbers. If testing was free, that would be a different story.

The positive Covid test also brought a new anxiety: would I be able to travel in three weeks? In order to get on a plane from Cusco to Lima, and now also to enter the US, I need a negative Covid test. Since the only rapid test here is for antibodies, I won’t be able to get a negative test again. The molecular test takes longer and since the test must be done within 72 hours of leaving, I might not be able to get that back in time. One of my parents’ friends had this problem on a flight to Hawai’i. Her results didn’t come back in time for the flight, so she rerouted through Portland, where you can get a rapid test in the airport.

Absent a negative test, I need medical clearance to be able to fly. That means, in the next three weeks before my flights from Cusco to Lima to Mexico City to Seattle to Boise, I need to fully recover and get a doctor’s note that I’m fully recovered. If I recover any slower than that, or have trouble navigating the red tape here to get the clearance, I won’t be able to travel. Rather than be anxious for the next two or three weeks about if I’ll be able to get medical clearance in time, I decided to postpone the trip. When I do reschedule, I will probably be a lot less anxious traveling, since I’ll be armed with antibodies. Even better, my parents will have the vaccine by then. They have an appointment for the first shot on January 29th, which seems to me like record time for Idaho. If I have antibodies and they have been vaccinated, my trip there will be much less stressful.

Meanwhile, there is another person with Covid in this story, and this one is my fault. Recently arrived from France, she had hired me to give her private classes in both English and Spanish. All arrivals from Europe in January were required to stay in their lodging for a two week quarantine, until the government shut down flights from Europe entirely. The entire world is freaking out about the new Covid variants in England, Brazil and South Africa, triggering more border closures around the globe.

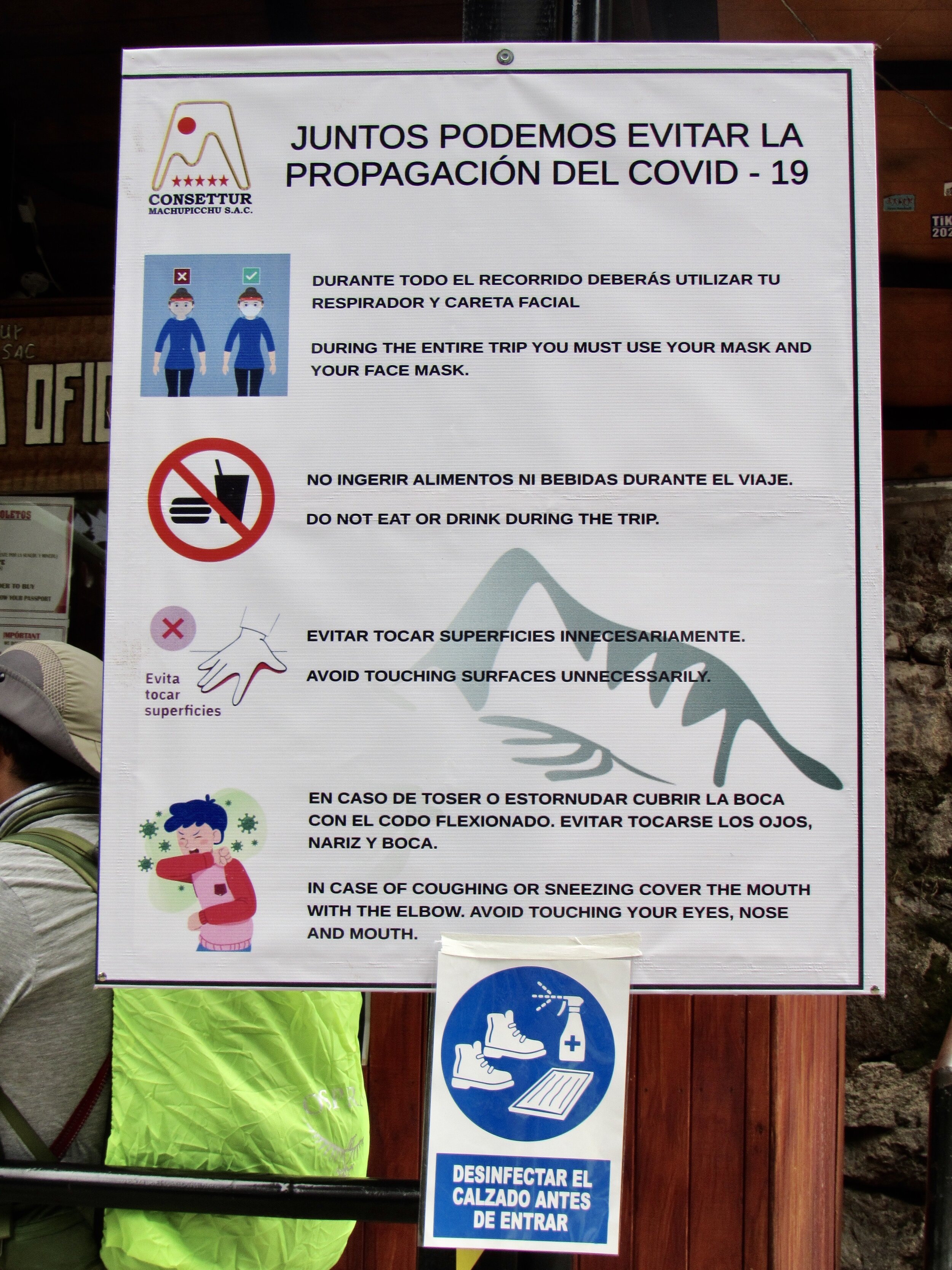

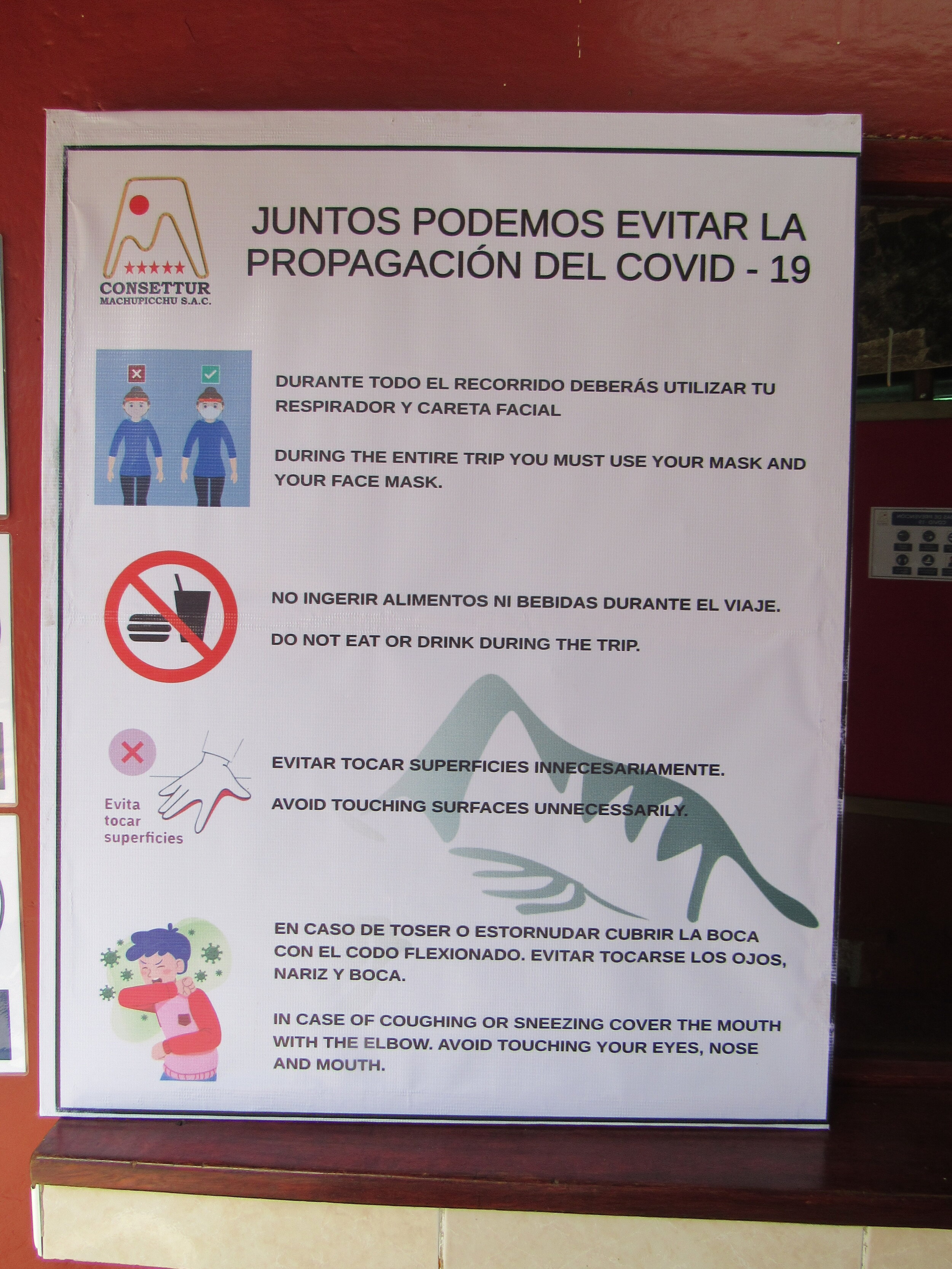

I wore my mask for my first two classes with her, nervous about her having recently arrived from Paris. I didn’t ask her to wear a mask and she didn’t seem at all interested in wearing one. She mostly stayed in her AirBnb, but did leave sometimes to buy food. As far as I know, I was the only person who visited her. So, as far as people I could have infected, at least she’s somebody without any friends or close contacts with here, and unlikely to continue to infect more people.

Unfortunately for her, the AirBnb owner figured out that she was sick and asked her to leave. This landed her in a hotel, since she didn’t have the energy to find an apartment or even another AirBnb. At the hotel, she was reported to authorities, who gave her a Covid test, which of course was positive. A local doctor was assigned to her, who visited her at the hotel and lent her a pulse oximeter, to check her blood oxygen saturation every two hours.

Having enough oxygen in Cusco can be a struggle in the best of times. At over 11,000 feet, it is common for new arrivals to be short of breath and to have blood oxygen levels of 80% or even lower. I also borrowed a pulse oximeter and was thankful to see my level was 94%, though the houseguest-turned-patient hovered just under 80%. This is a person who is from Cusco and who should be up in the high 90s. I wanted to send him to the hospital, but he was against it, so I asked a family member to come get him. The next morning, his niece came with a taxi to take him to a sibling who lives here in Cusco. He was far too sick for a drive to the Sacred Valley, even though his village is really only an hour away.

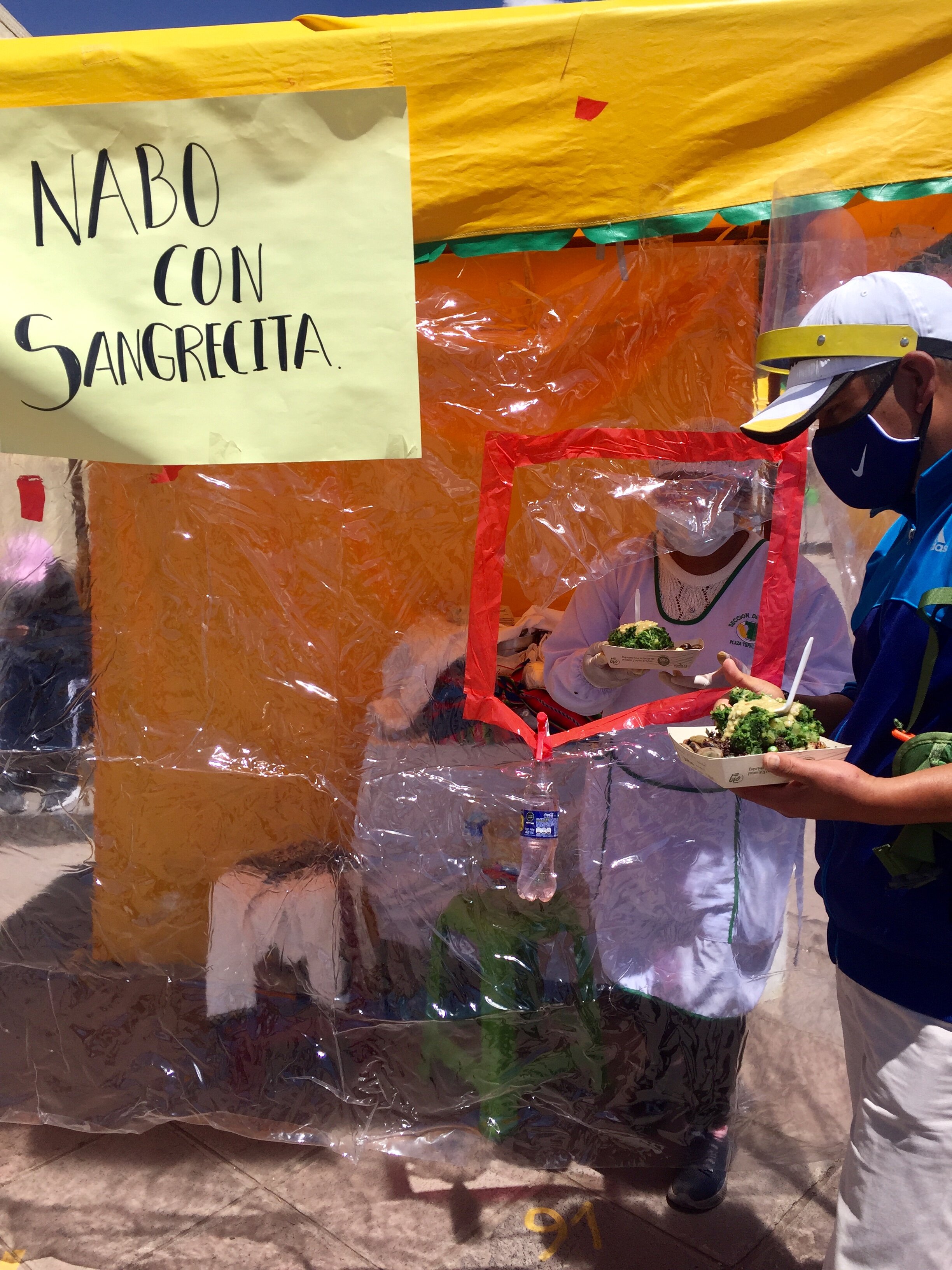

While he was in my care, I received a constant barrage of recommendations and medicine from various family members. One niece came with honey and navo, which is like a large radish. She hollowed out the navo and filled it with honey, instructing me to have him drink it in five hours. One sibling brought the antibiotic azithromycin, which just made him nauseous and gave him diarrhea. He only took one pill, then agreed with me that antibiotics weren’t going to help. In the absence of a positive Covid test, I had counseled him that even the regular flu was caused by a virus and that antibiotics couldn’t do anything about a virus. Even more worrisome, another sibling brought him a bottle of Ivermectin drops. He was told to take half the bottle one day and the other half the next. The package insert said nothing about Covid but instead referenced administering it to animals.

On a preliminary online search, I found that Ivermectin is used to treat parasites in animals. The FDA website answered the question “Should I take Ivermectin to prevent or treat Covid-19?” with the response “No. While there are approved uses for ivermectin in people and animals, it is not approved for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.” The article goes on to state that Ivermectin is approved for humans for “some parasitic worms” and that “Ivermectin is FDA-approved for use in animals for prevention of heartworm disease in some small animal species.” I recommended that he not try the Ivermectin and instead try a recipe from yet another sibling who had told him to finely dice red onion, garlic and ginger and put them raw in honey to soak for several hours, then take by the spoonful as a cough syrup. I figured that couldn’t hurt him.

Once I finally had my apartment to myself, I set about marshaling my friends to help keep me inside. Kerry got me fruit from the market and took my clothes to the laundromat. Steve got me cough drops at the pharmacy. David brought vegetables and cough syrup. Sonia brought oranges and a cinnamon roll. Andrea lent me three books and brought some chocolate chip cookies. I felt very well taken care of and had very few symptoms. Then I lost my sense of smell and taste. It was the strangest sensation. My mouth felt kind of numb, like the numbing effect of Szechuan peppercorns. If you haven’t had Szechuan peppercorns, think about how right after you brush your teeth, all you can taste is toothpaste. It kind of numbs your taste so that if you eat something immediately afterwards, you can’t really taste it.

I had been sick for over a week when it happened. First, some oranges that Kerry had brought seemed bland. I figured she had gotten ripped off. Then the mint tea that Sonia gave me didn’t have any flavor. Then I put a lot of garlic and ginger in my broccoli stirfry for lunch and that’s when I figured it out. The problem was not the oranges or the mint, it was Covid.

We’ve been hearing about this odd symptom since March. When the global news started to cover the pandemic in March, it was cited as a quirky Covid symptom and one that didn’t actually cause any harm. When testing was rare or non-existent, it was a way to know that you didn’t have the regular flu. For the curious, if I eat a raw garlic clove, I can taste that. I haven’t tried raw chili peppers yet.

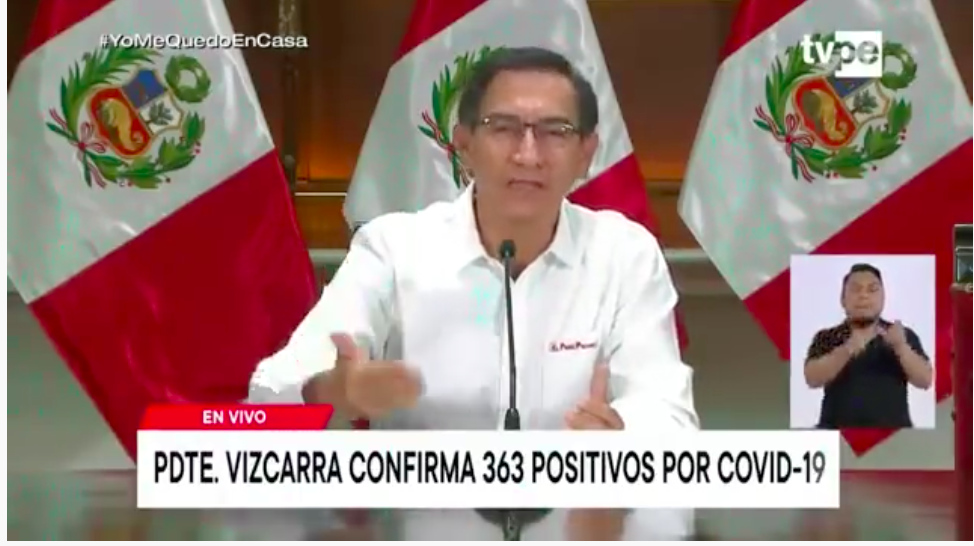

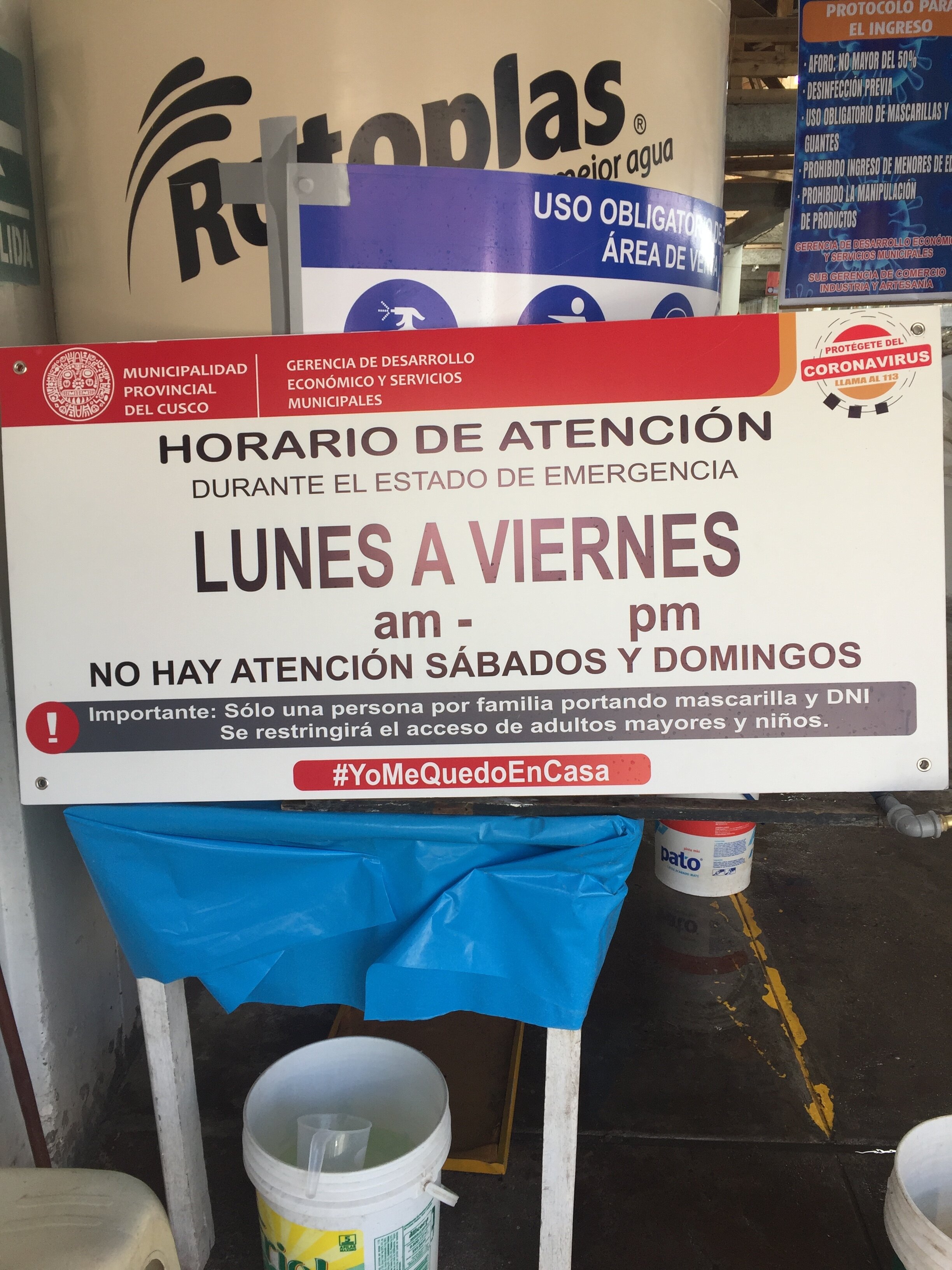

When we look back to then, it’s amazing how optimistic we were that this wouldn’t last very long. A few weeks probably, a couple months at the most. Over the 41 weeks that I blogged about the pandemic in Cusco, my tone goes from annoyed at having to stay inside, to surprised that this is going on so long, to excited that I’m living such a historic moment in Peru to resigned and bored. I went from obsessively reading all of the emails from the US Embassy in Lima to not checking my email for days at a time. I went from planning how tourism could be revolutionised to completely apathetic about the tourism industry. I started out listening to every address made by the Peruvian President Martin Vizcarra, often playing the YouTube version repeatedly as I did my own translation and transcription of his speeches for my blog. When he was deposed with a “constitutional” coup, I didn’t bother to listen to either of his replacements’ speeches.

In May I was so fired up about creating the Covid Relief Project and taking food to isolated mountain villages, that needed to stay isolated to avoid a Covid outbreak. By August I was worn out on fundraising and increasingly scared about taking Covid from Cusco to any of these villages. None of the eight we had visited had any Covid cases in the area and I was terrified of the consequences of taking the virus there. None had any access to healthcare, whether that be hospital, government clinic or even pharmacy. Several didn’t have electricity or running water in any of the homes. I rallied for December and raised enough money for another six villages but was so relieved to call the project done after the last village on January 6th. I just didn’t have it in me to keep going.

Looking back over my blogs, I’m reminded of my 2014 blog “Goodbye Bangladesh,” written six months after I had left the country. Sometimes I need some space, some time, before I’m ready to reflect on an experience. The pandemic has now gone on for so long that I want to reflect on it, except that we’re still in it. Early on when I heard people say that we were “in the middle of a global pandemic,” I would remind them that we were still at the beginning of a global pandemic. Now that we have several approved vaccines, are we in the middle yet? I’m certainly in the middle of my own Covid infection. With numbers of cases still rising around the world, can we say that we’re in the middle? Or perhaps past the middle? Could we be closer to the end?

I wish I knew the answer to that question. I wish I could write a blog counting down, instead of continually counting up. This is week 46 since Covid-19 was first diagnosed in Cusco and since the start of the quarantine and lockdown in Peru. Once we hit 2021 I just couldn’t keep up the same weekly blog. It felt too endless. It still feels endless and I’m still wishing that I could start some sort of countdown. I wish I knew when Cusco would be able to get back to normal.

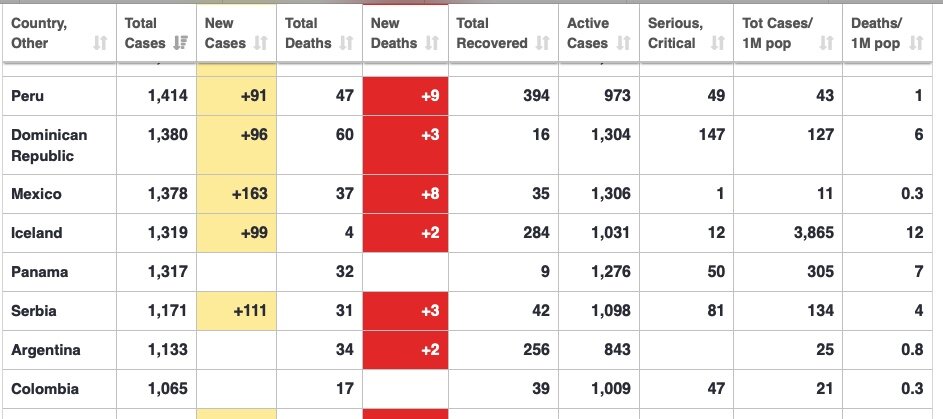

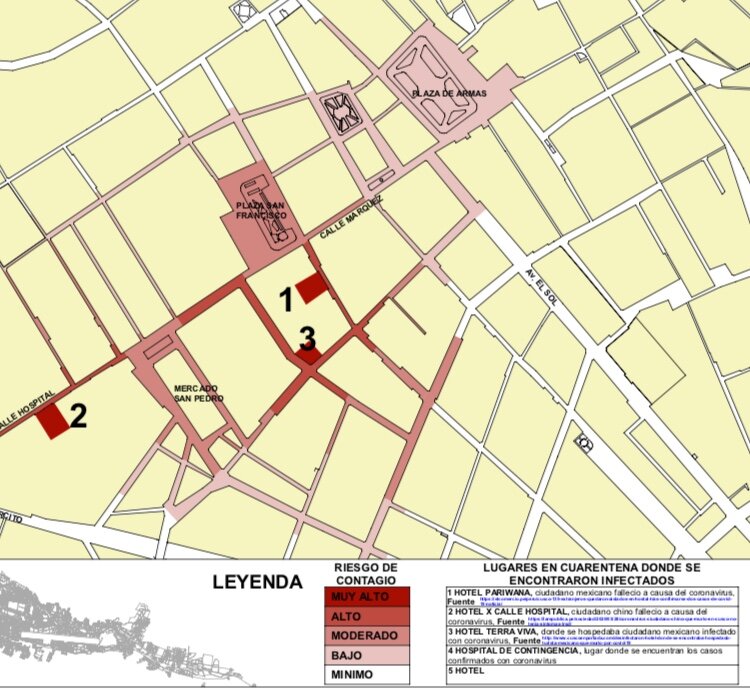

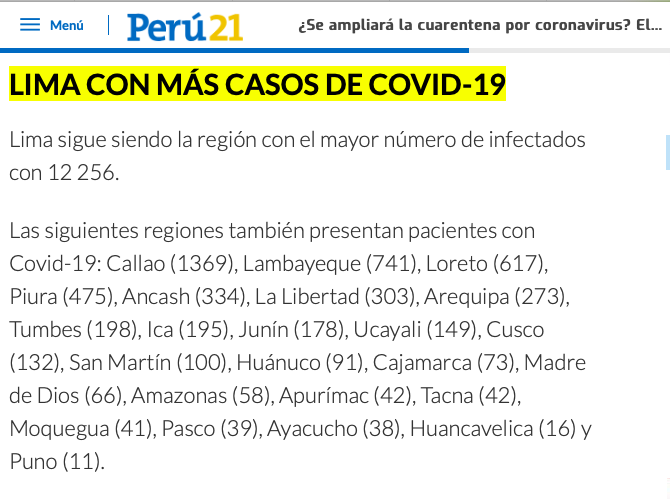

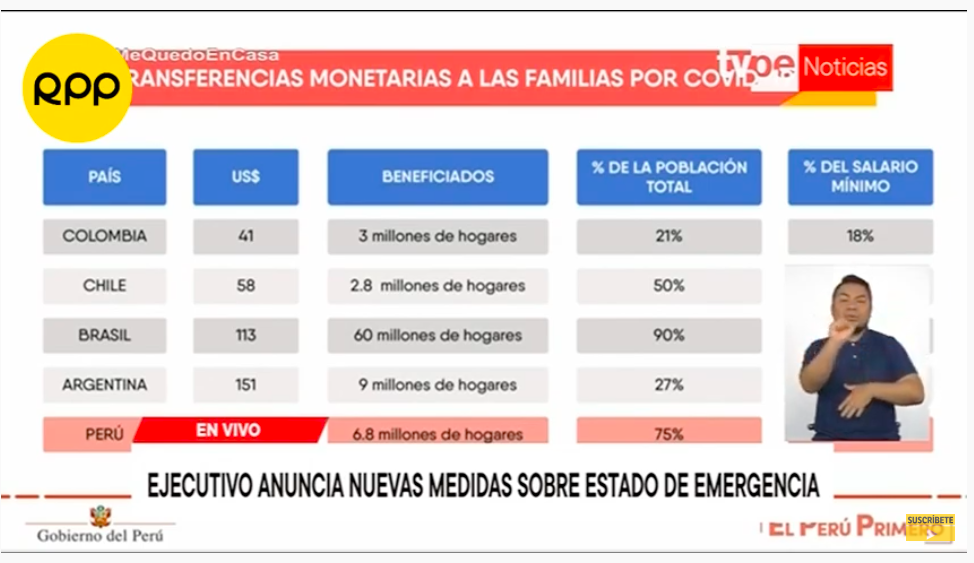

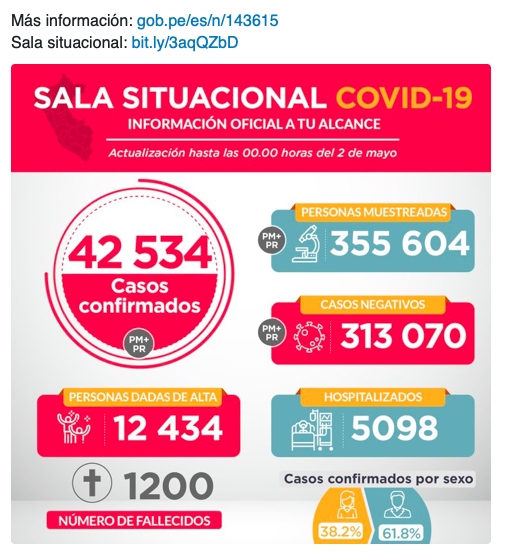

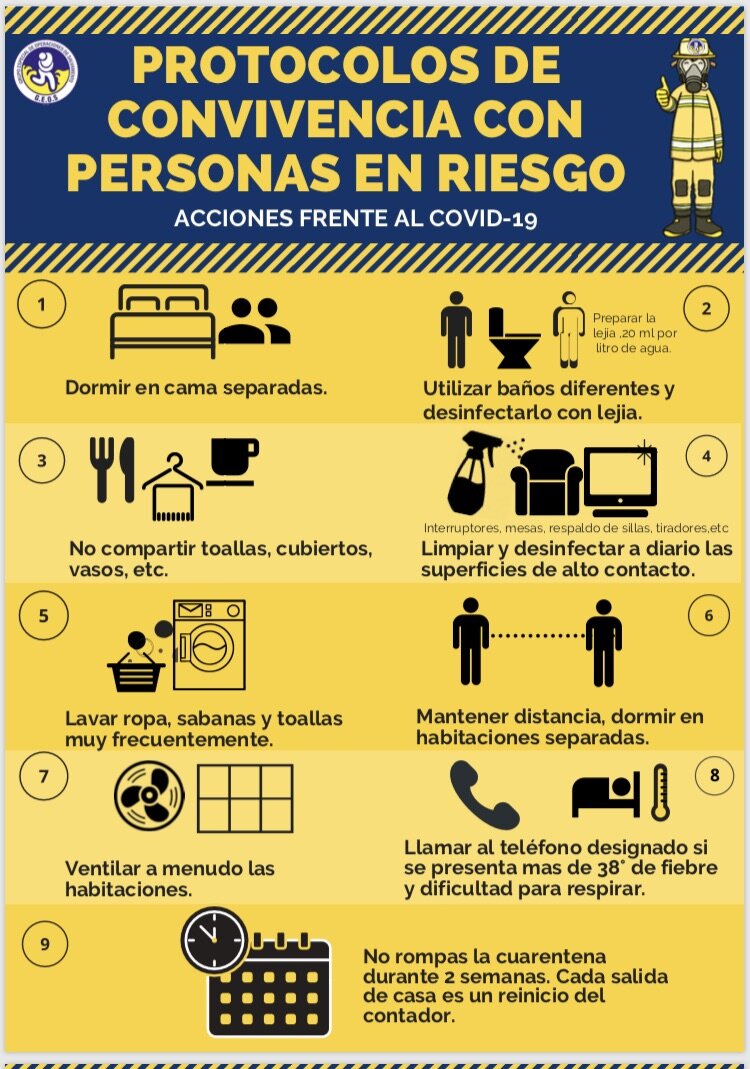

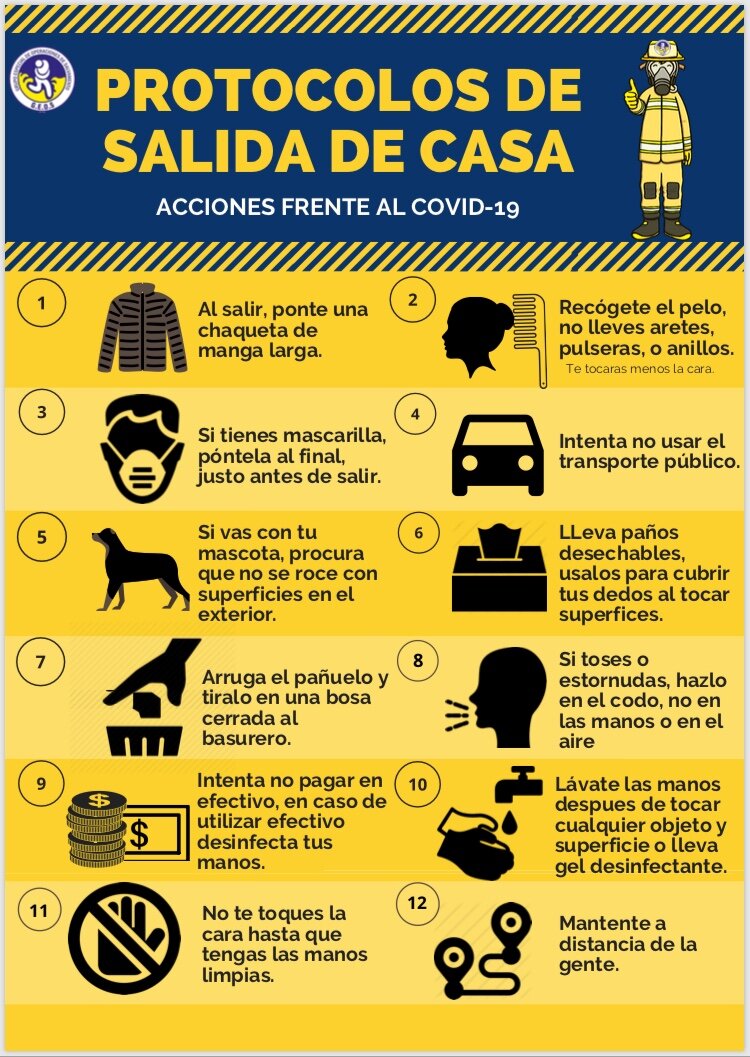

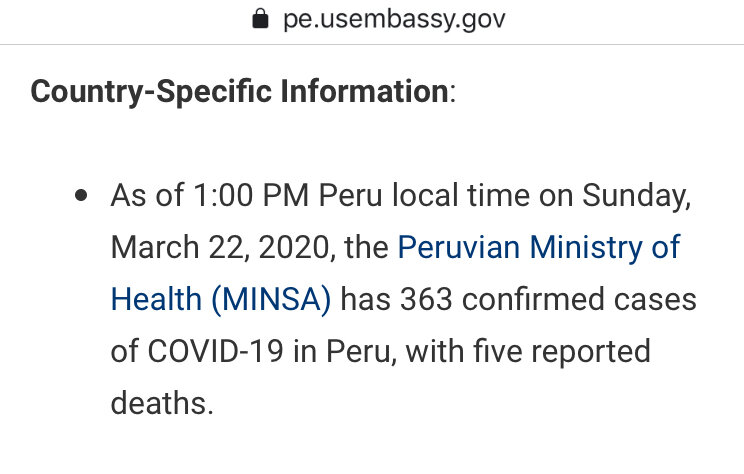

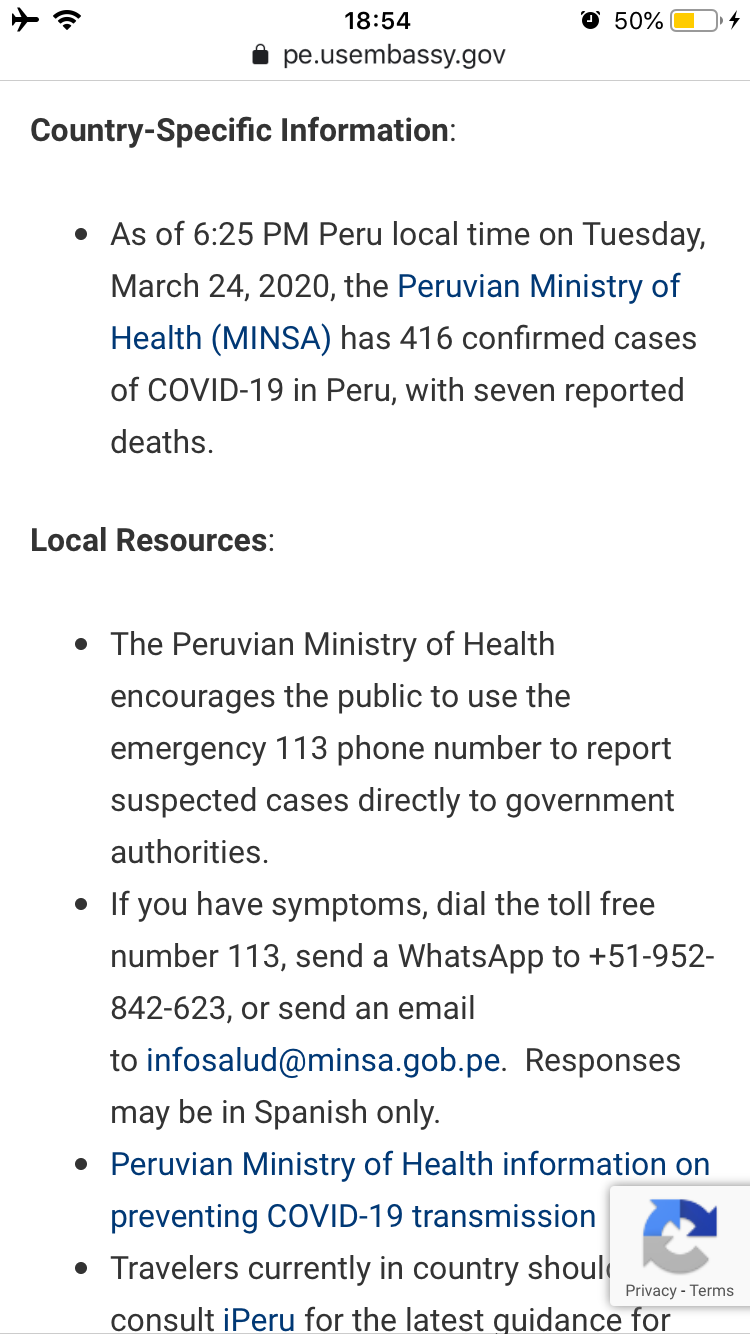

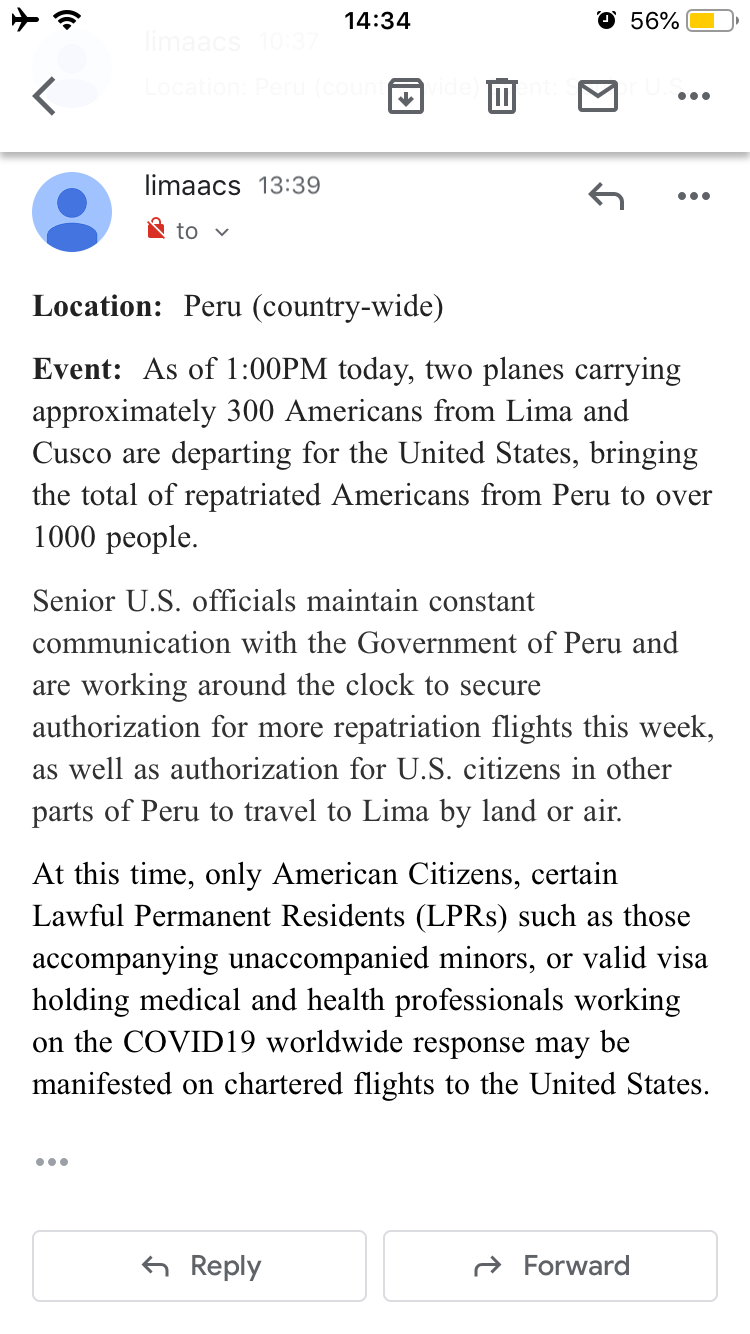

For a trip down memory lane, below are some of the emails I received from the US Embassy in Lima, and also official numbers and information from the Peruvian government. I watched the numbers of cases in Peru climb, as well as the number of American evacuated to the US. Throughout the evacuations, the pandemic situation in the US was much worse than in Cusco and I felt safer staying here. I still think it was safer to just stay put than to travel, even on a repatriation flight. It’s amazing how shocked I was when we had more than a handful of deaths in Cusco. I was so sure that we would escape the pandemic in the beginning. I thought that Cusco would stay isolated until it was over. I put a lot of stock in a National Institutes of Health study about altitude having a significant effect on the virus in terms of both transmissibility and severity. Since then, another study has shown that it’s less easily spread, but just as deadly.