COVID in Cusco: Week 22

Sunday, 9 August, 2020

149 days since Covid arrived in Cusco. 365 days since I arrived in Cusco.

I was woken up today by a call from my parents. My Dad had bought me a cake and put candles in it to celebrate today being my one year anniversary living in Cusco. It doesn’t feel like it’s been a year already, probably because almost half of that year I’ve been quarantined in my house.

The lockdown in Peru started on March 15th and was immediate. There was no easing into it here. One day things were normal, the next day the military and police patrolled the streets to keep us inside. In June and July some restrictions were lifted, but many have been put back in place for August. My favorite of these restrictions (no sarcasm) is the full day Sunday curfew. Nobody is allowed to leave the house except for emergencies on Sunday. That means that the construction workers outside my windows won’t be here today.

So much has happened in the past year. I’ve learned so much and seen so much! I was here for only seven months before the pandemic hit, but in those seven months I managed to hike the short Inca Trail, see Machu Picchu for a fourth and fifth time, hike the Lares trek, go see the northern coast of Peru by the Ecuadorian border and visit Paracas National Park and the Islas Ballestas. Most of those trips have their own blogs, but there were also so many things I learned that aren’t the normal topics for my blogs.

I learned how the tourism industry works in Cusco and I learned about all of the different treks besides the Inca Trail. From all of my experience as a traveler, it was easy to know what information would be most important to them and how to best convey that information. Still, it was my first time working in sales and customer service since I had sold kayaks for Idaho River Sports in the summer of 1999.

I learned a lot of Peruvian vocabulary, some of which comes from Quechua. Here an avocado is called palta, a pen is lapicero, a t-shirt is polo and boiled potatoes are papa sancosecha. I also learned a lot of Quechua. I can say all of the greetings like good morning and good afternoon and ask people how they are. I can say all of the goodbyes including see you tomorrow and goodnight. I know tree names, birds and other animals. I can give a toast, especially when drinking chicha. I can talk about the weather and food.

I learned more about Inca history, culture and architecture. Having already visited Cusco three times, and read a lot of books, I arrived thinking that I already knew a lot. However, living here I am surrounded by the history, culture and architecture. I don’t need books. I just need to look around me and talk to people about what I see. Learning from real people is so much better because they can not only give me a synthesis of the most accepted theories from multiple archeologists, they can also answer my questions on the spot.

I learned how to work in an office where I was the only non-Cusqueñian. I was the sole English speaker in the office, so all communication had to be in Spanish. I learned to understand their jokes and sense of humor. I really think that understanding another culture’s sense of humor is the most difficult part of learning their culture. When I was able to counter their jokes with my own, everybody in the office noticed and I felt so much more included.

I learned how to travel with a group of Peruvians. If you have read many of my blogs, you have noticed that I usually travel alone. This was a “retreat” for office staff, with the plane tickets and lodging paid for by the company owner. Twelve of us flew together to Lima, then on north to Piura, continuing in a van up to Máncora. Going along for the ride, on a trip that my manager had planned, every day scheduled with group activities and sharing a hostel room with five other coworkers was like nothing I have ever done before.

The following five months are well documented with my weekly blogs. I am still learning Quechua and some Inca history and culture, but nothing like before. I am trying to still spend time with Peruvians, though all human contact is severely limited by the pandemic.

It hardly seems like I’ve actually been here for a year. The past five months have been a holding pattern, with a few days of activity sprinkled in. Most of those days were with the Covid Relief Project, taking food to families in need. A very few were hikes outside of Cusco, where I got to see something new and learn about a new place, like Huchuy Q’osqo.

Like many of us around the world, I feel like I’m on a layover, stuck in an airport. Being on a layover is technically still traveling, on the way from one place to another. Still, it’s not really being anywhere at the same time. I’ve spent a few hours in the airport in Zurich, but I wouldn’t say that I’ve been to Switzerland. I’ve been in quarantine in my house in Cusco, but I wouldn’t say that I’ve really been living in Peru. I’m just sitting on the couch, like most people I know.

Monday, 10 August, 2020

I was a teacher for twelve years before I moved to Cusco and have been following the situation for many of my former colleagues around the world. I have taught in Boise, Idaho; Istanbul, Turkey; Dhaka, Bangladesh and Seattle, Washington and many of my colleagues from those places have spread out around the world. Some countries have things more under control than others, of course. Schools in Australia sound like they’re well organized. Some international schools have gone completely online, for the time being.

The second year I was in Bangladesh, was an election year. Elections, and the lead up to the elections, can be very violent in Dhaka. There were many days that it was unsafe to leave home and school was cancelled. There were even more days that it was unsafe to leave home in most of the city, but teachers and students who lived near school were able to get to school relatively safely. This led to the policy that we were to teach in person the students who were able to come to school and simultaneously teach online the students who were at home. It was really hard.

I have so much sympathy for teachers who are trying to teach online for the first time, even if they had somewhat of a crash course in teaching online at the beginning of the pandemic, as school in the US was near the end of the last academic year. Teaching online is so much more time consuming for teachers and so much less effective for students. Some people in Peru are already throwing up their hands in exasperation over the situation. Some are talking about this being a “lost year,” that students shouldn’t be penalized for.

The academic year in Peru was just starting when the pandemic hit. Just before the beginning of the new school year, President Vizcarra postponed opening schools. On March 11th, he announced that public schools, which were scheduled to open on March 16th, would be postponed to March 30th. Private schools which had already started the school year were ordered to close. At this point, on March 11th, there were only 13 confirmed cases of Covid in Peru, and none in Cusco.

Then, the date for opening school was postponed over and over, just as our quarantine was extended over and over. Eventually, the minister of education announced the program “Aprendo en casa” or “I learn at home.” This is a national curriculum, broadcast every day online, on tv and on the radio. Private schools have created their own online courses, but don’t have access to broadcasting on public tv or radio, like public schools. Many teachers here for both public and private schools have had to make their own YouTube channels so students can watch the lessons or extra help, when possible.

The teachers I know here are exhausted. They spend way more time planning than they used to, since teaching online is so much more complicated. Also, they get questions at all hours from kids and most feel compelled to answer immediately. Teachers know how much kids need answers to their questions. They want to be there to answer their students’ questions. How does that work when there are four kids in the house and one computer to share, so that not all of them can actually do their work during normal school hours?

Even more poignant, how does that work when nobody in the village has electricity, much less the internet or a tv? How does that work when a family lives so high in the Andes that there is no radio signal near their village? In the Peruvian village of Qhantati Ururi children have to walk for miles to get to an area that has a radio signal. These kids spend two to three hours a day walking, just to listen to the radio. This is an area just south of Cusco, but to be honest, there are plenty of villages in the Cusco region that face the same problems.

The same article about Qhantati Ururi cites the heroic efforts of one teacher in Huancavelica who walks about 10 kilometers per day to visit students. It was hard enough for me to teach online in Dhaka, where all students had access to a computer and were capable of getting online during class time. How can you make that work for kids who live in communities without electricity?

Another challenge is getting support at home, when the teacher can’t get to the kids or when they can’t send their questions to their teacher. All around the world, parents are trying to figure out how to both work and help their kids learn at home. Some parents can work from home, but that doesn’t mean they actually have time to both work and be a learning support specialist. Some parents are unable to stay home and have to either leave the kids home alone while they go to work or find somewhere else to take them.

What about the parents who can’t help because they’re illiterate? In Peru the percentage of illiteracy had gone down to 5.9% by 2018, but that includes the whole country. I am absolutely positive that in communities where the people don’t have electricity or a radio signal, many more than 5.9% of the adults are illiterate. Over 17% of women in the Cusco region are illiterate, down from 23.4% in 2008.

Interestingly, trying to find literacy statistics for 2019 or 2020 proved to be impossible. The government here has been so unstable that I would not be surprised if they had been unable to do the necessary work to calculate those statistics in the past couple years. I give them a pass for 2020, since doing anything normal now is next to impossible. Still, the complicated politics of Peru also made 2019 a loss in terms of accomplishing normal tasks. (It’s a long story, but worth reading. Here’s an English version.)

So, while I really do sympathize with my former colleagues in the US, they are mostly teaching kids who have access to the internet. At the very least, their students all have electricity. Most of their students have literate parents.

Traveling to rural communities with the Covid Relief Project, to take food to families in need, I have seen plenty of communities without electricity. I have been to remote valleys that don’t have cell service and probably don’t have any radio signal either. I have met a lot of parents who are very likely illiterate. I completely understand why some people here in Peru would throw up their hands in exasperation and start talking about the “lost year.”

Tuesday, 11 August, 2020

This morning I went to the San Blas market and realized how weird the new normal is. The cop at the entrance to the market, watching us wash our hands barely even registers anymore. I automatically wash my hands, thinking about what I need to buy rather than how sad it is that the pandemic has forced us to have to wash our hands to go buy food. In weeks, if not months, I haven’t even noticed that more than half of the stalls in the market are empty. I have learned to just look at the ones that are open.

The same two women I used to buy from before the pandemic are still there, so my shopping habits haven’t really changed much. However, the woman I used to buy coffee and chocolate from is gone. Little by little, I bought out her stock of chocolate and coffee throughout March, April, May and June. Every time I complained that she wasn’t getting in any fresh coffee and she would tell me that the roasters in Cusco were closed. All she had was what she had in stock before the pandemic. Every week her selection of chocolates was worse. First I bought all of her dark chocolate with almonds, then all of her dark chocolate with pecans, then the quinoa and kiwicha. Then, a couple weeks ago, her stall was boarded up. I haven’t seen her since.

The woman I buy veggies from is near the entrance of the market. She’s a thin woman, well under five feet tall, with some gray at her temples. I usually buy onions, tomatoes, peas or fava beans, sweet potatoes or one of the other ten varieties of potatoes she stocks, cauliflower or broccoli, bell pepper and spicy chillies, a cucumber and some basil or swiss chard. I get leeks if I’m going to make a lentil soup and eggplant if I’m going to make a green curry. She also has dried black beans, lentils and garbanzo beans. Black beans are hard to find here, which is one of the reasons that she’s my go to veggie stop.

My fruit lady looks very young, but she has told me that she has a fourteen old daughter, so she must be older than she looks. Since the pandemic started and the market emptied out so much, she is often knitting when I walk over to her spot. She knits baby clothes, which is why I initially thought she must be in her early twenties, with her first baby. Nope. She just likes knitting baby clothes. She gives them to friends and family. I usually buy a papaya or two, oranges for juice, mandarines, passion fruit, bananas and avocados. Avocados are always sold at fruit stands, never at vegetable stands.

I usually spend 30 to 40 Peruvian Soles, which is about $10USD. The quality of the produce here, and the low prices, are what makes being unemployed in Cusco livable for me. On the way out of the market there is another hand washing station. I’m always so weighed down with my bags that I squirt a little alcohol gel on my hands and just walk home. I often think that my fabric bags will break one day, but I have definitely tested them and they have held so far. It’s normal for me to have up to ten kilos in the veggie bag - a kilo each of onions, potatoes, peas, tomatoes, cauliflower plus a bit of everything else. The fruit bag is usually lighter, but still heavy enough that I’m glad home isn’t uphill from the market.

Wednesday, 12 August, 2020

Today started with a hike up past the Temple of the Moon with my friend Hannah. She’s the one I teach Spanish to on Monday evenings. We made it a gentle little walk, very unlike my illegal hikes back in March and April, when I was trying to get up to the top by sunrise and back home before anybody noticed that I had left the house for something other than food or pharmacy. On those hikes, I was walking uphill as fast as my lungs would allow. Today, it was much more of a leisurely stroll.

Walking outside is still legal - for adults. I cannot for the life of me understand that government’s position that those under 14 are a special risk group and should not be allowed out of the house. After months of a complete prohibition on children leaving the house, they are now allowed a half hour outside for exercise, accompanied by an adult and following social distancing requirements. From what I have read, children under 14 aren’t actually a special risk group for Covid. After almost five months of reading that in Peru children under 14 are at special risk for Covid, I’m still at a loss as to where this idea came from.

Hannah moved to Cusco for similar reasons to mine. She thought it would be a nice place to live and that she would be able to find work here. After years in the fashion design industry, in the UK and US, she found work in Cusco with knitting. Specifically, with women knitting in prison. Prison labor has a bad history in the US, but Denmark doesn’t have the same history, or the baggage that comes with that history. Hence, the brand Carcel, from Copenhagen.

Carcel means prison in Spanish, but for some reason it’s a brand name that works in Europe. The company employs women in prison, training them on specialized knitting machines. The mission of the company is to give women skills that they can use to get a job, after they leave prison. This arrangement is not without moral and ethical complications. Done even a little bit wrong, it ends up being exploitation. Done right, women in jail can earn a living wage to send to their families back home. Also, women leaving jail can get a good job and support their families when they do get back home.

According to a 2018 study by the Universidad de Ciencias Aplicadas (University of Applied Sciences) of Lima, six out of ten Peruvian women have committed drug related crimes. That is a staggering number, which I found unbelievable before I read the whole study. Most of these women were economically and socially vulnerable: uneducated single mothers who struggled to earn enough to support their children. Most were coerced by a family member to transport drugs, told that women are never suspected or arrested.

Hannah truly loves her job and the women that she works with. From what I can tell, the Carcel brand is doing things right. It really doesn’t look like exploitation to me. They are knitting expensive alpaca sweaters for exportation to Europe. They are earning a very livable wage and do benefit from a lot of training. Still, prison labor laws in the US prevent Carcel from exporting to the US.

The pandemic has made absolutely everything more complicated, including how often Hannah can enter the prison. I haven’t read about Covid spreading in prisons in Peru, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that was a problem. In the US, it is definitely a problem. I am just hoping that the tragedy in Seagoville, Texas won’t be repeated in Peru.

Thursday, 13 August, 2020

The San Blas market is by far the closest to my house, but the San Pedro market is both the biggest and the most touristy. Of course, nothing is very touristy now, since borders have been closed for almost five months. I went on a search for fabric, as part of one of my ideas of what to do with myself as Peru goes back into lockdown. Yesterday President Vizcarra signed another Supreme Decree, telling us to all stay home again. Curfew for the whole country is now 8pm six days a week, and all day on Sunday. Many of the freedoms allowed in July are being taken away.

Sewing has always been relaxing for me. I live in a country of alpaca and sheep, surrounded by knitters, but knitting has always been more frustrating than relaxing for me. The women here seem to knit while doing everything else. They knit while selling fruit at the market, while watching sheep in the fields, while waiting for the bus and while on the bus. Back when people were allowed to be near each other, I was constantly surrounded by women knitting.

I am hoping that sewing will make me feel productive and useful. It’s something that I can do that doesn’t involve looking at a screen or a whole lot of thought. If you’ve made it this far in this blog, then you know that I love writing. However, lots of screentime is not good for any of us and I have been looking for things to do that give me the satisfaction of creating something, without spending hours on the computer.

Peru is not only a country full of yarn and knitters, there are also amazing textiles woven here. I went to a few fabric shops next to the San Pedro market and each was full of beautiful fabrics. I honestly could have spent all day in each one. They all had machine woven fabrics and also more rustic, handwoven fabrics. I settled on two meters of a rich brown and purple machine woven fabric and a handwoven blue with multicolored stripes. I also got a length of woven ribbon, one of hundreds of options at the shop.

The prices of fabric here are shockingly low. For the meter of ribbon I paid s/1 Peruvian sol. For the machine woven fabric I paid s/24 for two meters. The handwoven was twice the price, at s/50 for two meters. Still, s/75 is only $20, with the current exchange rate. That should be enough to keep me busy at least through the full day Sunday curfew this weekend.

Friday, 14 August, 2020

Knowing that Sunday I won’t be able to leave the house, I’ve planned hiking trips for both today and tomorrow. Today I’m headed out of Cusco through the San Cristobal neighborhood, then up through the Sacsayhuaman archeological area and around to Tambombachay and back down into my neighborhood Lucrepata.

It turned out to be about 7km/4.5 miles of easy walking. All archeological sites are supposed to be closed, but Sacsayhuaman is also a thoroughfare from Cusco to a few small communities in the hills above town. I had no trouble walking along the road, though when I stopped to take photos of the ruins a guard blew a very loud lifeguard kind of whistle at me. I waved so he would know I got the message. Every access point to the ruins, all of the stairways that are over 500 years old, have been roped off with red tape decorated with skull and crossbones that says Peligro (danger).

I was close enough to town to be sure that there were no ronda campesinas in the area - communities that have taken it upon themselves to create a security force to keep outsiders out. It’s really important for isolated mountain communities to stay isolated during the pandemic, but the communities within easy walking distance of Cusco are far from isolated.

It was a beautiful and relaxing walk, without any drama or difficulties. If only I could stay that about every day!

Saturday, 15 August, 2020

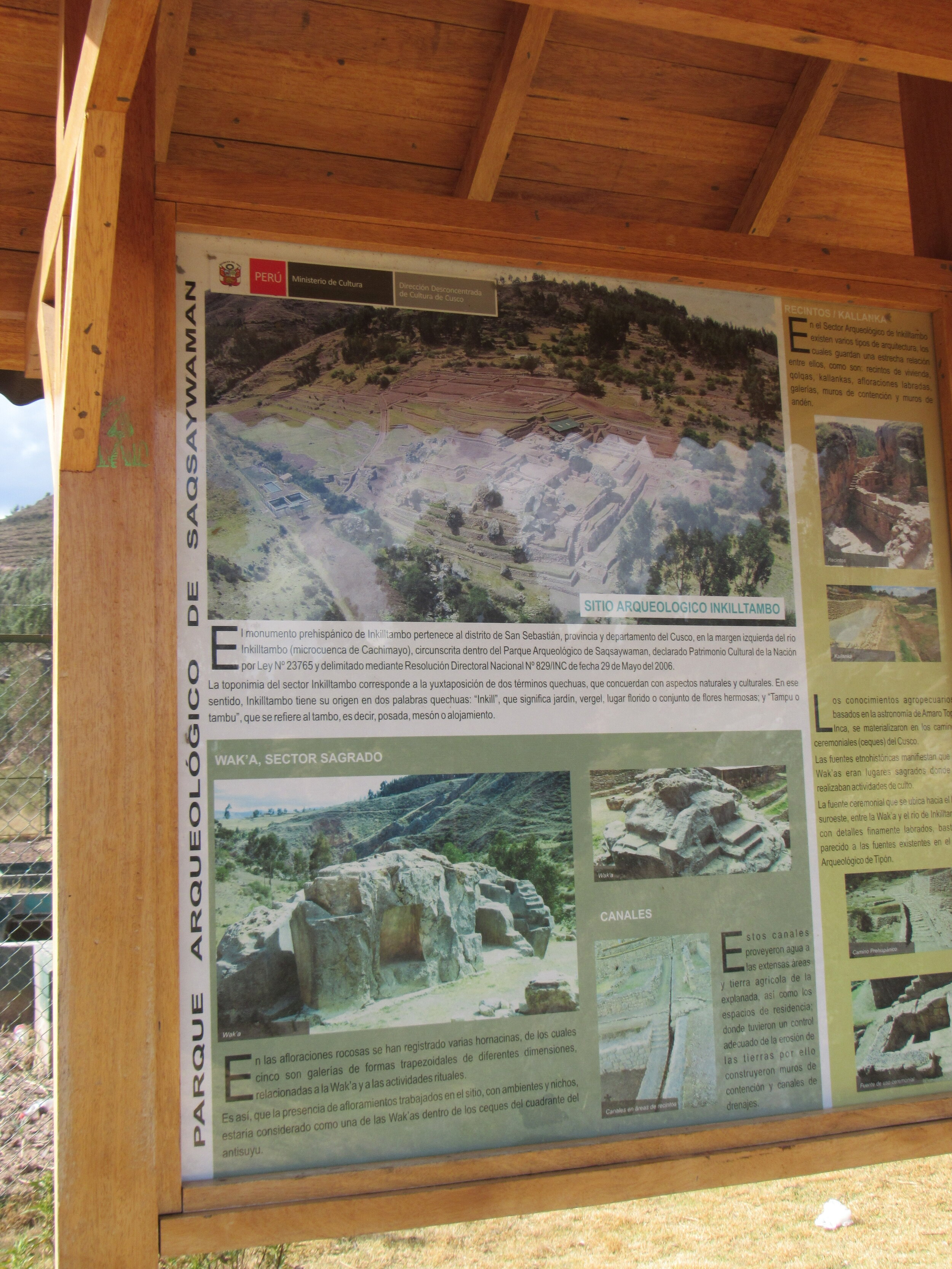

I went with a group of four friends to hike to Inkilltambo and have a picnic today. I have learned to greatly appreciate being able to do anything that reminds me of normal life. Of course, we were wearing masks when we were around other people, but when it was just us on the trail, we got to take them off and breathe normally. There was some uphill on today's hike and it makes such a big difference when I can take off my mask to hike uphill. Today we hiked about 10km/6.3 miles and according to my phone, climbed the equivalent of 86 floors of stairs - at 3,400m/11,200ft above sea level.

We started at my house, which is very close to the trail up to the Temple of the Moon. Past the Temple of the Moon, there is a sign for Inkilltambo, pointing down the valley that parallels the valley Cusco is in. I’ve hiked by it many times, but since I’m usually just trying to be out in the mountains, I've never stopped to explore the place. I know that sounds ridiculous, but there really are so many Inca ruins all around and throughout Cusco that you just can’t spend time at all of them.

Inkilltambo is actually pre-Inca. The name comes from the Quechua word inkil, which means garden or small field. Tambo is a resting place, a place where the inhabitants would take in travelers. Most of it is terraces for farming, but there are also several areas that obviously were collections of homes. Though it is a protected archeological area, some of it is still being used for agricultural purposes. We saw more than one herd of sheep, plus several cows and goats grazing on the terraces. If it had been llama or alpaca I could have more easily imagined the place as it was when people really lived there.

Like many places around Cusco, anything pre-Inca became Inca. The place looks like it was a small community, perhaps just a few families. Inkilltambo has the usual division of three areas: terraces for farming, religious buildings and an area with homes and workshops. The religious area includes several wacas, which are ceremonial buildings. There are aqueducts linking the terraces to several water sources. There are two large kilns near Inkilltambo, which were used for firing ceramics. A lot of restoration work has been done on the kilns, so they probably look like they did 500 years ago.

The whole area has actually gotten a lot of recent restoration work and new signs. Although very separate, it is strangely included as part of the Sacsayhuaman archeological site. We walked around the ruins a bit, then walked downstream to a spot that Sonia has been wanting to have a picnic. The five of us sat by the water, passing around tortilla chips, guacamole, fresh salsa, uchucuta sauce, tiny purple potatoes, homemade bread, cheese, wine and chocolate. It was the best picnic I’ve had in a very, very long time. Sitting by the stream, sharing food, we had totally escaped the reality of pandemic life.