School Supplies for Airepampa

We took school supplies, fruit, clothes and school furniture to Airepampa on March 27, 2021.

Saturday, March 27th, we arrived in Airepampa after over three hours on narrow mountain roads, the last two hours on a rough dirt road. The night before, Elio Huaman Bolívar came from Calca with a truck to pick up the donations from Escuela Inmaculada Concepción, where Henry’s sister Yanet Morales Loaiza was storing our donations. Yanet also donated books, desks, tables, chairs and whiteboards from her school. We are so grateful for all of our donors in Cusco who also gave us yarn, clothes, shoes and hygiene basics like shampoo, toothpaste and toothbrushes. On Friday morning, we purchased 150 notebooks, 300 pens, 150 pencils, 50 coloring books, 50 sets of colored pencils, 150 small towels and 500 oranges. Towels may seem like an odd addition, but personal hygiene is a struggle in rural areas like Airepampa and anything helps. Thank you so much to all of our donors who sent money for the school supplies!

¡Gracias a Yanet y a la Inmaculada Concepción Cusco!

We are so grateful that Yanet was able to donate books, desks, tables, chairs and also a bookcase for Airepampa! She also donated for our previous school supply drive for the village of Japu, Q’ero Nation.

Thanks also to Henry, Elio and Auqui for hauling all of the desks down from the third floor and loading them in the truck.

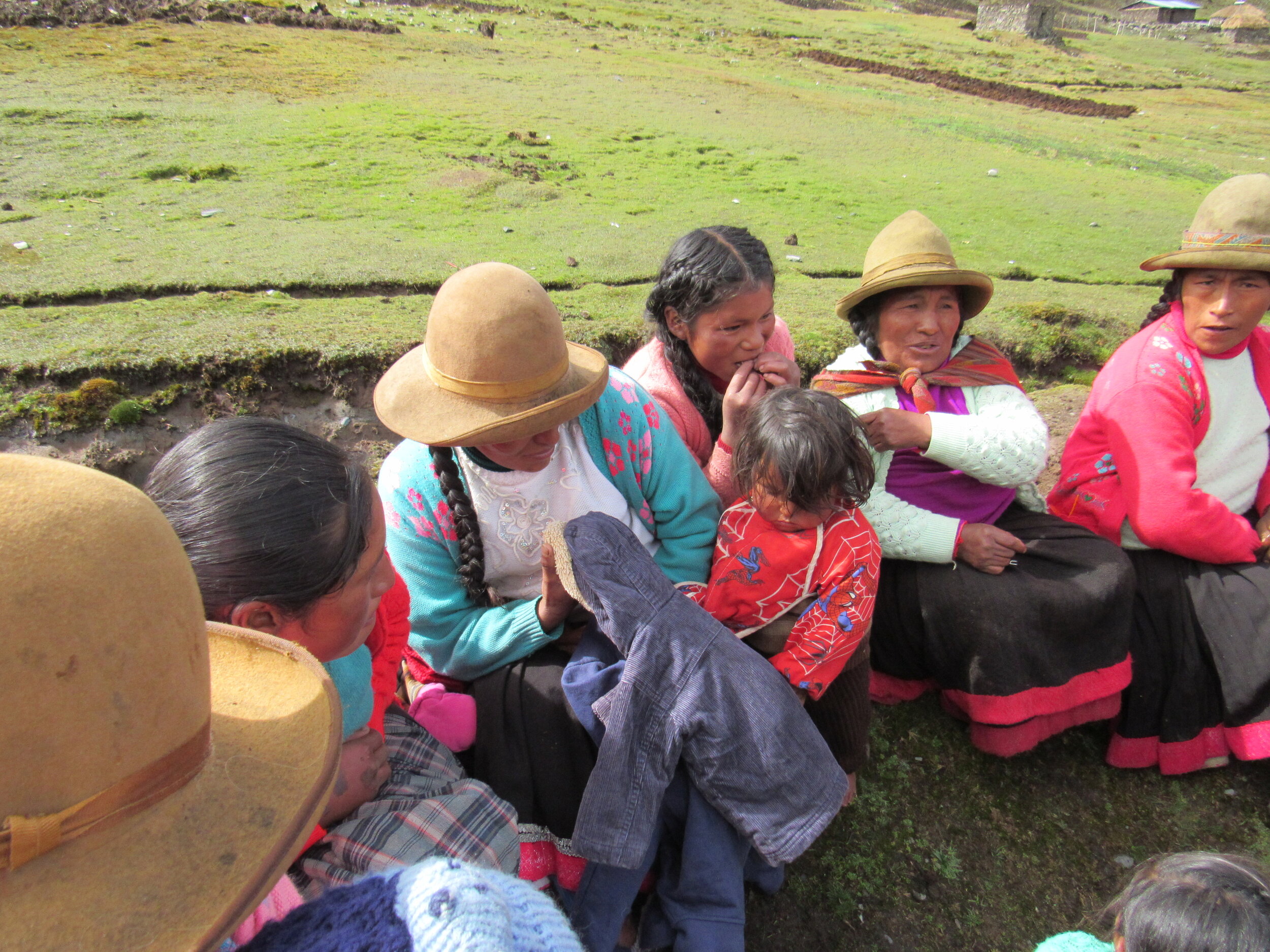

When we took a chocolatada to these communities last December, we had first stopped in Ttio Grande to do a chocolatada there, then drove another half hour to Airepampa, where we held a second chocolatada on the same day. This time, we stopped in Ttio Grande to pile as many people as possible in the truck with the donations, and in the back of the pickup that had come to pick up Auqui and I in Cusco. We squeezed a couple young mothers with babies and the smallest children in the back seats of the pickup and everybody else climbed in the pickup bed. It's a twisty mountain road, so there was no way we were going to be going fast anyway, but the driver Carlos was extra careful on the last leg of the journey to Airepampa.

The mood was festive, just like the chocolatada had been in December. March is the start of the new school year, not the holidays, but with the continuing pandemic, there hadn’t been any big celebrations or gatherings since the December 5th chocolatada. The kids of Ttio Grande were excited to visit their friends in Airepampa and everywhere I looked the kids were smiling and laughing with each other. Elio introduced us to José Antonio Fernández Castro, the teacher in Airepampa. Like most teachers in rural areas, he lives in town and comes to the village only on week days. He had ridden his motorcycle two hours on the dirt road from Calca to help with the event. He graciously allowed us to interview him and we learned a lot about education in Airepampa, one of five “microcuenca” which are communities too small to count as villages.

The Teacher

José Antonio Fernández Castro worked hard all day but stayed in the background, checking on his students to be sure each age group got the appropriate school supplies. Teachers like José, who drove two hours each way from his home in Calca on his motorcycle on a dirt road to spend his Saturday with us, are my greatest hope for rural Peru.

Like all of 2020, schools are closed due to the pandemic and teachers are supposed to teach online. This is impossible in places like Airepampa where there is no cell service or radio signal, let alone internet. José and his colleagues visit each family once per week to drop off worksheets and pick up completed work. This is incredibly frustrating for all involved and José convinced a few of his students to talk to me about how they really feel about the government program “Aprendo en Casa.” Every one of them said that Aprendo en Casa was too difficult, that they want to go back to regular school and that they know that they’ve fallen behind significantly. One of the ironies of the situation is that Airepampa, and the other microcuenca, have stayed so isolated that there are no cases of Covid in the area, even more than a year into the pandemic. They really feel like they should have been able to have school last year and they definitely want to go back to normal school this year.

We had plenty of hands to help unload the truck and set the donations on the tables that they had lined up where we had held the chocolatada. We started with the coloring books, colored pencil sets and towels for the smallest children who are not in school yet. Then we gave pens, a pencil, a notebook and a towel to the primary school kids, followed by the secondary school students. Most of the girls wear a cloth tied around their shoulders, called a queperina, which serves as a backpack and purse. In some regions of the Andes, both men and women use them, but in Airepampa none of the boys were wearing one. While the girls put the school supplies in their queperina and got back in line, the boys had to hang onto the school supplies or just set them down somewhere. The second round was oranges and clothes, which were equally popular. Some of the kids were wearing clothes that I recognized from when we distributed clothes here last December. Some of the kids were familiar too.

After we had distributed the items that we had enough of for everybody, we called over some of the community leaders to ask about handicapped adults in the area. We had about a dozen skeins of yarn, plus knitting needles, which one person said he would take to a woman who is homebound. The other basics like shampoo, toothbrushes and toothpaste went to other handicapped adults in the area. It’s hard enough for able-bodied people to get from Airepampa to a dentist in Calca and next to impossible for those with physical handicaps.

It was afternoon by the time we were finished distributing everything, at which point the presidents of the three microcuenca that have schools divvied up the books, desks, chairs and tables evenly amongst each other. Everybody is hopeful that before too long they will be allowed to have classes in person again and when that day finally comes, the schools will be ready.

Elio, Carlos, Auqui and I were invited to share lunch with the community president’s family. It was the same place we had shared potatoes and cuy in December and today they had both alpaca and cheese to accompany the potatoes. When we first arrived that morning, we were greeted with huayro potatoes, my favorite of the pink potatoes. For lunch we were served maqtillo, which is my favorite of the purple potatoes. There are over 3,000 varieties of potatoes in Peru, so it’s a miracle that I actually knew the names of the ones we ate.

Also that morning, while the truck was still being unloaded, I spotted Sonia Suli Sulorseno, who works for the government’s Vivienda agency. She had hitched a ride in the truck to come out to inspect the water source at Airepampa. Only a couple years ago, the regional government invested in water filtration systems for the communities in this area. Some homes still do not have access to water, but most now have a tap just outside the front door. Sonia was here to check the filtration system and the level of chlorination in the water, which she said is crucial because of the high number of parasites in the water here. I asked her a bit about living conditions for children and she said that almost all children here have anemia because their diet is almost entirely potatoes. At this altitude, few other plants can grow and Sonia also helps distribute vitamin tablets with iron for the kids here.

What’s it like to live in Airepampa?

Sonia gave me the hard facts that I wouldn't get just watching the kids play or having a casual chat with their parents. She was here to check the filtration system on the new water source since the water here has a high parasite content. I asked how bad anemia really is, since I see public service announcements about it all the time, but never got any numbers on how many kids it actually affects. I asked her if it was just a few kids or maybe half? She said that almost every child in Airepampa suffers from anemia.

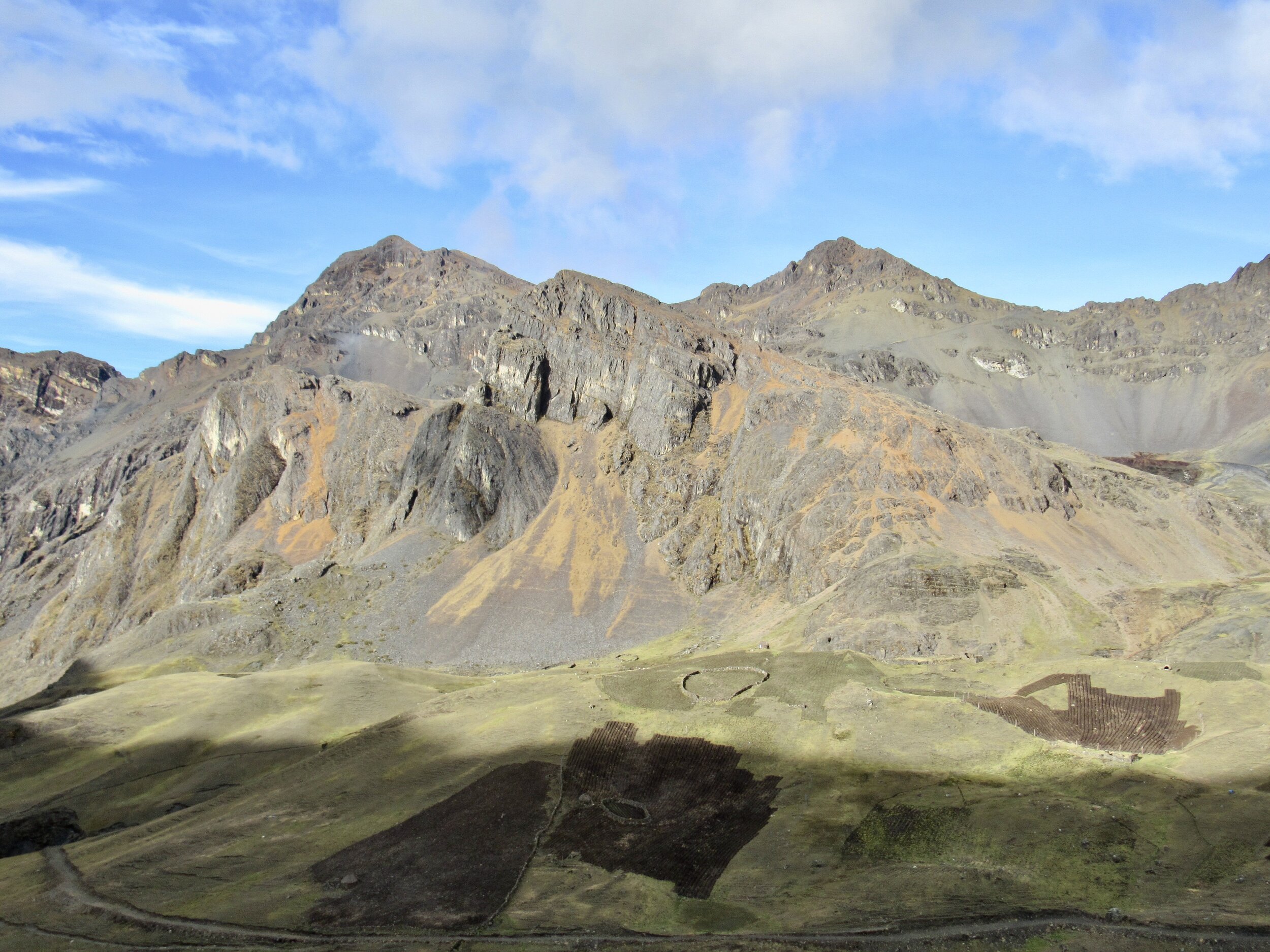

Airepampa is far from everything, is on a steep hillside, doesn’t have any natural resources like trees or streams nearby and the land can’t grow much besides potatoes. Yet, it is beautiful in the way so many high-altitude areas of the Andes are. The mountains have their own beauty that those of us who live in cities usually envy. If only we could get adequate medical care, internet or cell service and education, preferably in Quechua, to Airepampa, it would be a wonderful place to live. As it is, young adults flee as soon as they are old enough to find work in Calca or another town or city. Here’s hoping that the services these families deserve reach them soon.

As one project ends, another inevitably begins. Our food aid deliveries from last May through August turned into holiday chocolatadas, which turned into a school supply drive. Now, we are looking for a way to encourage children to value their native language and culture. As essential as education is, in Peru it is always in Spanish, which quickly devalues and eventually erases Quechua. The world has already lost so many languages, taking with them the cultures with which they were intertwined. There are still enough Quechua speakers left that this is a language that can be saved, but only if it’s speakers find it useful. For centuries, Quechua speakers in Peru faced discrimination if they tried to live in or even visit a city. That has changed, but now that so many are moving to cities, they are leaving their language in the countryside. We are looking for ways to sponsor poetry competitions in Quechua and are open to other ideas about how we can promote the value of Quechua. If you have any ideas, or want to get involved, please emails us at covidreliefcusco@gmail.com

Thank you! ¡Gracias! Añay!

P.S. It’s amazing how fast kids grow! Check out how much this little guy grew between December 5th and March 27th!

P.P.S. In December I came away from Airepampa so worried about kids having nothing but ojotas to wear. They’re made from used tires and are almost the only shoe worn by children and adults alike. I’m still worried about that.

Siusa chocolatada

Our sixth and final chocolatada was in the village of Siusa, high in the mountains above Pisac. Along with panettone and hot chocolate, we took clothes for children and food for each family. We are so grateful for our donors whose generosity made all of these chocolatadas possible!

Our sixth and last chocolatada was a beautiful day! Just under three hours from Cusco is the village of Siusa. The community has electricity in some homes, and most have a well nearby. However, the closest healthcare access is over an hour away, in Pisac. There is a primary school but several parents told us that the teacher did not visit once during the 2020 school year. During the pandemic, all students were supposed to stay home and access the national curriculum by internet, public tv channels or public radio stations. Siusa does have radio, but teachers are still supposed to check in with students regularly, collecting completed assignments and giving feedback on previously collected work. Many small communities are ignored by local governments, especially the more isolated mountain communities. Unfortunately, nobody advocated for the children of Siusa during the pandemic and they did not get the support that they needed.

As with our other five chocolatadas, we started out the day by distributing clothes to children, while the hot chocolate was being made. When we arrived the community had two giant cauldrons of boiling water ready. We added 30 liters of fresh milk to each, along with a one kilo bar of pure cacao, a handful of cloves and several cinnamon sticks. We always make sure that they bring the milk to a boil, since we buy unpasteurized milk directly from a dairy.

Everybody had been instructed to bring a mug and while not everybody had a mug, some had bowls or even old soda bottles. We made sure that everybody got hot chocolate and panettone before we let the children have seconds on the hot chocolate.

After the chocolatada, the community president asked one representative from each family to come receive the food donations. Each family received 5 kilos of rice, 2 kilos of sugar, 1 kilo of salt and 5 bags of oatmeal. We buy salt with iodine and fluoride, two elements that are not present in the normal Andean diet of potatoes, corn and quinoa. Many of the villages that we visit are at such high altitude that they can only grow potatoes and are hours from the nearest market where they could trade for corn or quinoa.

We finished distributing the donations around noon and were invited by Jacincto, the regidor from Calca, for something to eat. We were each served four boiled potatoes and a fourth of a roasted guinea pig. Almost every community wants to share something with us after we finish the activity. They share what they can, which for some communities is only boiled potatoes or boiled corn. Whatever it is, we are always happy to be able to take some time to talk with the community leaders. It’s our opportunity to ask more about how the pandemic has impacted them and what services are available in the village. None of the villages that we’ve visited has a pharmacy, government clinic or hospital nearby. Most of them do not have any kind of public transportation and leaving the community is very difficult. More importantly, every one of them has managed to stay so isolated that they do not have any cases of Covid. We hope that they all manage to stay safe until the Peruvian government can distribute a vaccine.

As always, I am so, so, so grateful for all of the people who donated to make this possible! I am also very thankful for the help of all of our volunteers here in Cusco! Henry & Auqui have done all of the organizing with all of the local governments for each of these events, working with ten different mayors offices and town halls. Today we also had Auqui’s nephew James and niece Blanca helping. Henry brought his cousin Franklin and friend Meliza to help as well. Sair Camargo Luque, who came to help at the village of Marampaqui on December 19th, also joined us for the day. It makes such a huge difference to have so many hands able and willing to pitch in for everything from hauling bags of rice to distributing clothes. ¡Muchísimas gracias a todos!

Hatun Q’ero

Our second chocolatada for the Q’ero Nation was at the village of Hatun Q’ero. We also took clothes for children and food for each family. This community lives in a high altitude valley, hours from the nearest town with healthcare access. Their isolation has kept them safe from the pandemic so far and we hope that taking food to them will help them stay in the mountains, away from exposure to Covid.

This was our second village of the Q’ero Nation. Hatun Q’ero is about a six hour drive from Cusco, which is why we asked the mayor of Paucartambo to send transportation that could pick us up at 5am. The night before he had sent a large truck to pick up twenty desks which were generously donated by the school where Henry’s sister teaches. Of course, the school has been closed all year due to the pandemic, so nobody has gotten to use these desks in 2020.

All of the villages of the Q’ero Nation are part of the district of Paucartambo. Last Sunday, Sofia, who works in the Paucartambo’s mayor’s office, organized everything for our visit to Japu. Unfortunately, she was not available this weekend and we didn’t have anybody like her to help everything go according to plan. We were at the Maytaq Wasin, ready to load the food and clothes, at 5am. When Auqui called to check how close the trucks were, we were told that they were just leaving Paucartambo. That meant, the best case scenario would be that they would get to Cusco two hours late.

Henry, Auqui and I have gotten used to long hours on twisty mountain roads, and very long days, but I was a bit worried about our other volunteers. Kara and Katie were visiting from the US and had barely had 24 hours to acclimatize in Cusco. I wished that they had been able to get another two hours of sleep. Wilbert and his daughter Miska, Auqui’s brother and niece, were also joining us for the first time. We wanted them to enjoy the day, which was already going to be long, even without the extra two hours hanging out near the hotel. Henry’s niece Lucero was with us, but she’s already come to both Mayubamba and Marampaqui, so this wasn’t her first impression of how things go with the Covid Relief Project.

Eventually, two extended cab 4 wheel drive pickups arrived. We piled 160 bags of rice, two sacks of 300 oranges each and the two cans of 30 liters of fresh milk in the first pickup. The second pickup got 160 bags of salt, 320 bags of oatmeal and eight sacks of children’s clothes. It was almost 8:00 when we left, which meant that we didn’t get to Hatun Q’ero until almost 2pm. Nothing had been open in Cusco so early on a Sunday morning, so none of us had eaten breakfast. The community hadn’t prepared any boiled potatoes or anything else for us, plus there wasn’t really any time for lunch anyway. I am so thankful for all of our volunteers, who stayed helpful and cheerful during a very, very long day!

It was cloudy and snowing a little when we arrived, but thankfully in a couple hours the sky cleared and we had a few hours of sun. We started with the distribution of children’s clothes while the hot chocolate was being made, like we have done with the previous four chocolatadas. As always, many people did not have a cup, but thankfully somebody had a key for the school and they brought out the cups that children used to use during lunchtime. We served the children first, then Lucero went around to collect the cups from the children to be used again by the adults. Somebody in the community brought us a bucket of water with some bleach in it, to rinse out the cups.

There are no cases of Covid in the area, so the worst they could catch from each other would be the sort of cold that people passed around before the pandemic. Coming from Cusco, we are always very aware that we are the greatest danger they have faced since the pandemic began. We keep our masks on and I make sure that anybody handing out panettone is wearing gloves. Considering that we are outside, as long as we keep our masks on, the risk of one of us spreading Covid to them is very low, even if we are infected and asymptomatic.

After everybody had hot chocolate and panettone, the community president called out names from a list of heads of household while we distributed 4 kilos of rice, 2 kilos of sugar, 1 kilo of salt, 2 bags of oatmeal, 2 oranges and an extra panettone to each person. In theory, one adult representative from each family is supposed to receive the donations. In practice, many elderly people who live alone are not able to walk to the village and somebody has to stay out in the mountains, watching the alpaca. Often, children watch alpaca, but since we were giving out children’s clothes, and since hot chocolate is so popular with children, many parents sent the kids to the village and stayed to watch their alpaca. Several men came through the line four or five times and we teased them about how many families they had, although we knew that they were going to be taking the food to families that were unable to send an adult to the village. Also, there were many elderly people who had come to the chocolatada, but who were unable to walk through the line carrying about 8 kilos of food. Young men came through the line, then took the food over to their elders. I assume that they also helped them carry the food home at the end of the day.

We are used to sitting around after we distribute the donations, sharing food or just chatting with the villagers. Unfortunately, it was already past 4:30 and we really had to hit the road. It’s about two hours on very rough dirt roads from Hatun Q’ero to Paucartambo. From Paucartambo to Cusco the road is paved, but it gets dark not long after 6:00 and those mountain roads are much more dangerous after dark. The dirt roads from Hatun Q’ero to Paucartambo do not have any guardrails when there is a big drop off, or where the road is particularly narrow. The drivers honk when we drive around a sharp corner, in case somebody is coming in the opposite direction that we can’t see, but that only warns people. More than once there were alpaca in the road, which are as unaware as a cow would be of what a car honking around the corner would mean. Thankfully, alpaca are quite skittish and afraid of anything loud, so they generally flee at the sound of a car, truck or motorcycle. Few people can afford a truck out in the mountains and cars really can’t handle those roads, but there are always a couple families who have a motorcycle for going to town. It’s very dangerous to drive a motorcycle on those roads after dark, but sometimes you just can’t get home in the daylight, no matter how hard you try.

It was after 10:00 when we got home, tired and hungry, but happy to have been able to help the families of Hatun Q’ero, despite the logistical difficulties. I do hope to be able to go back some day, perhaps spending the night in Paucartambo so there is less of a drive to the village. I would love to hear from the Q’ero how the pandemic is affecting them and how they are experiencing the effects of climate change.

Marampaqui, Ocongate

The Covid Relief Project took a chocolatada to the village of Marampaqui, at the foot of Mt. Ausangate. Besides the chocolatada, children received warm clothes and each family received donation of rice, sugar, oranges and panettone.

We had the most beautiful day for the chocolatada at Marampaqui! Today went pretty similarly to the previous three chocolatadas. The first task is to make sure that the women making the hot chocolate got the chocolate, milk, sugar, cloves & cinnamon. They already had a giant pot of water boiling on a fire, in a grassy area next to the one room school house. They added the cloves, cinnamon sticks and chocolate to the water, to be sure that the cacao was completely melted. After it was boiling they added the 30 liters of milk and brought it to a boil again, since fresh milk must be boiled. When it started to boil over, four people lifted it off the fire and set it on the grass. The last step was to add the sugar before we could serve the hot chocolate.

While we were waiting for the hot chocolate to be ready, we handed out clothes to the kids. Grimaldo Quispe, the mayor of Ocongate, helped hand out the clothes, along with the other volunteers who came with us today. Auqui and Henry were there, as always. We also had Henry’s niece and nephew, Lucero and Max. Two friends, Kerry and Sair, who backpacked around Ausangate with me, also joined us. They had gone through Ocongate at the beginning and end of the backpack trip and were eager to see the area again. We had a beautiful view of Mt. Ausangate from Marampaqui, although clouds gathered over the mountain by mid-morning, so we only had a clear view early in the morning.

Then we had the chocolatada, making sure that everybody got a panettone and at least one cup or bowl of hot chocolate. Lots of kids had forgotten to bring a cup and lived too far away to go home. They either borrowed somebody else’s cup or found a water bottle or something that could hold liquid. We did our best to be sure that everybody got hot chocolate and I hope nobody got left out. I would estimate that at least four hundred people came to the chocolatada.

After the chocolatada, we gave out the oranges, rice and sugar, along with some leftover panettone. Unfortunately, Saturday is also market day in Ocongate, so there were quite a few adults missing from Marampaqui. The mayor of Ocongate was a huge help with calling out kids to represent their family and receive the donations. We really rely on local leaders to know who is in which family and keep track of who has already received their donations. By the end of it, there were still 16 families missing, so we entrusted their donations to the community president.

As both a show of gratitude and to help us get ready for the drive back to Cusco, the community served us a big tub of boiled potatoes and little pats of soft, fresh cheese. It’s always interesting to see what a community wants to share, or more like, what they have to share. This is the first time we’ve been given cheese and it was delicious. Cheese here is not cured with rennet. It’s more like fresh cheese curds. They add vinegar or lemon juice to the milk until it curdles, then squeeze out the extra liquid. Depending on how it’s made, it can be a lot like Indian paneer. After our lunch, we all piled into one car and headed home.

Coca

At the market in Ocongate, we bought two pounds of coca leaves before we drove to Marampaqui. The coca leaves are for the elderly people who come to the chocolatada. We have clothes for the kids and 4 kilos of rice and 2 kilos of sugar for the adults. I’ve felt like we’ve left out the village elders a bit in the past, so this time we made sure to have a little something for them too.

Coca leaves are chewed and give you the same effect as a cup of coffee and an ibuprofen. They’re great for headaches, or any kind of aches for that matter. Hence, their popularity with the elderly. They can also be used to make cocaine, but it takes about 600 kilos of leaves to make one kilo of “cocaine base,” according to Recovery.org. In my experience, the leaves themselves are much less addictive than coffee.

Coca leaves are also very sacred in all Andean traditions, despite the fact that they’re from the Amazon jungle, not the Andes. However, the harsh life in the Andes, especially living at high altitude, often requires medical assistance of some sort. The oldest medicine in South America is coca leaves and they have taken on special cultural significance because of what seems to be magical powers.

The logistics

We are still buying the food we donate from Wagner’s, where the owner Jorge gives us what he can at cost and arranges for us to pick up the supplies or delivers them to the Maytaq Wasin. The Maytaq Wasin Boutique Hotel continues to be our base of operations, where we store clothes and food that will be donated. Henry is working with a local baker and dairy farmer to get us freshly baked mini-panettone and 30 liter cans of fresh milk. The mayor of Ocongate arranged both transportation for us and lodging in Ocongate, so that we could do more of the drive Friday evening and be able to start the chocolatada earlier on Saturday.

Thank yous

I am so thankful for Kerry and Sair’s assistance on this trip! They are both hard workers and it was a joy to see Kerry playing with the children while we waited for the hot chocolate to be made. I really appreciate the support of Grimaldo Quispe, the mayor of Ocongate, who jumped in to hand out clothes or do anything else that was needed. His support of the Covid Relief Project also gave us a great team from his office who helped with everything from transportation and our lodging in Ocongate, to notifying families of the event and helping distribute donations. As always, I am so grateful for all of the countless hours of hard work that Auqui and Henry continue to put into this effort. We have taken this project so much farther than I could have hoped when we started back in May.

Japu, Q’ero Nation

Our third chocolatada went to the village of Japu, which is part of the Q’ero Nation. This community is about six hours from Cusco and you need 4 wheel drive for the mountain road. This isolated mountain community still lives a very traditional lifestyle, although they still need basic communication and healthcare. There is no cell service or radio signal in their valley. The nearest healthcare is three hours away, if you can get a ride. The village is at the end of a rough dirt road, so few vehicles ever go there.

Today we drove for over five hours from Cusco to the village of Japu (pronounced Hapu), which is part of the Q'ero Nation, north of Cusco in the Paucartambo district of the Cusco region. The Q’ero are known for their very traditional lifestyle. They did not allow any contact with the outside world until the 1990s, because they believe that they are the last descendents of the Inca and wanted to protect their culture and language from modern influences.

They still live a traditional lifestyle, but since their school opened over ten years ago, the younger generation is also learning Spanish. Most men in the community are healers and lead Andean spiritual practices. Some also consider themselves Catholic, as most people here believe that there is no conflict between believing in God and believing that we must respect and thank the earth and natural world around us. Traditional Andean beliefs include a wide variety of practices, but the most important for the Q’ero is the Pachamama ceremony.

There are 80 families that live in the valley of Japu, though less than half of them live in the village. There is a school that opened over ten years ago, but it has been closed since the pandemic started. The teachers only came a few times all year, according to one of the fathers I asked. There is no healthcare available in Japu and the road to the nearest town with a government clinic is at least three hours away in the town of Ocongate. The people of Japu are farmers but at their altitude of over 4,000 meters, the only crop that will grow is potatoes. They also have beautiful streams and eat trout. They shared some boiled potatoes and fried trout with us after the event. Today’s event had four stages: clothes for kids, chocolatada, food distribution and a final frenzy for oranges.

We brought clothes for all of the children, which we distributed while the hot chocolate was still being made. We had separated out a bag for babies under a year, bags for both girls and boys under five years old, bags for kids 6-10 and bags for tweens and teenagers. The clothes distribution went quickly, then we brought out two giant cauldrons of hot chocolate. We had brought with us 3 bars of pure cacao, each one weighing a kilo. We also brought cinnamon sticks, cloves and sugar for the hot chocolate. We brought a metal can straight from a dairy with 30 liters of milk in it. We made sure that they boiled the milk before we served the hot chocolate. We buy fresh milk because it's more nutritious and also it avoids all kinds of packaging waste. We were careful to take our trash out with us, since they obviously don't have any way to dispose of trash other than in their beautiful valley.

After everybody had a panettone and seconds on the hot chocolate, we asked one representative from each family to come receive 5 kilos of rice, a liter of vegetable oil for cooking, 1 kilo of salt with iodine (which is almost impossible to get up in the mountains) and two bags of oatmeal, which is fortified with vitamins and minerals for children. Malnutrition and anemia are serious problems up in the mountains.

Before we left, we gave everybody two oranges each. They were even more excited about the oranges than the hot chocolate and panettone. Several of the smaller children just ate the oranges as if they were apples, peel and all! I have no idea how often fresh fruit gets up to them, since they are at the end of a very long dirt road. The road was built only ten years ago, before which walking was the only way to get to or from Japu. People there own llamas and alpacas, but I didn't see any horses. I don't know if that would be a transportation option for a person who needed to get out for medical help. There is no regular transportation to Japu, so most people only walk. There is no cell service and they don't get any radio signals either.

Below are photos from our trip from the main road to Japu, starting after we left the paved road that goes from Ocongate to Puerto Maldonado. The road to Japu, six hours from Cusco and almost three hours from Ocongate, goes up and over two passes. The highest of these passes is over 5,000 meters. I was thrilled to see vicuña, which are an endangered, wild cousin of the llama. They are quite rare and normally very skittish. Usually, you only see them off in the far distance and as soon as you stop to take a photo, they take off. They can run very quickly up steep slopes of loose scree. For there to be vicuña in the area shows that the Q’ero are really taking good care of their land. That the vicuña were so close to the road is evidence that not only do cars rarely come this way but also that poaching is not a problem in the area. Illegal hunting is a big problem in Peru because there is practically no enforcement of hunting laws. Only in very protected areas are endangered animals actually safe. Thankfully, the Q’ero still have a deep respect for and close relationship with the Pachamama.

Now, we need the government to provide education in Quechua and healthcare for each village in the Q’ero Nation, so that people can keep their language and culture, but also benefit from the services that other Peruvians are afforded in towns and cities. I hope that living conditions improve so that the children we saw in Japu are able to stay in their community and keep their language and culture alive.

THANK YOU TO SO MANY PEOPLE!

I am so thankful to the people who made today possible! The Weismen family of Chicago donated enough to cover all of the expenses of today. Auqui spent countless hours on the phone coordinating with local government in Paucartambo to provide transportation. Sofia Champi, who works in the local government of Paucartambo, coordinated the transportation and all of the communication with the community leaders of Japu. Henry has been working with bakers and dairy farmers in Cusco to get us the best mini-panettone and the best fresh milk. Sonia & David endured a very long day and a huge help with the entire event. Lupe Yucra helped buy the children’s clothes that we gave out and worked tirelessly all day with us. Jorge Wagner continues to work with us, as a wholesaler to get us the rice and everything else we buy. He also gives most of what we buy to us at cost, spending lots of time with us to get the right products at the best price he can find for us. These visits to villages are a big undertaking which required weeks of preparation and a big support network. Thank you to all involved!

Mayubamba & Paruro

We held a chocolatada in Mayubamba and at the elementary school in Paruro. The children of Mayubamba also received warm clothes and their families received rice, vegetable oil and hygiene kits donated from the Maytaq Wasin Hotel. The children in Paruro each also received eight bags of oatmeal and a package of cookies.

Today was our second chocolatada and we met at the Maytaq Wasin Hotel at 5:30, to try to get the truck loaded and hit the road as early as possible. Today’s drive was only about three hours, which is closer to Cusco than some of our other villages. However, Mayubamba still lacks a lot of basic services. There is no government clinic and no regular transportation to or from town. Very few people in Mayubamba have vehicles or even horses. There is no cell service and only one radio station reaches them. Since all education in 2020 is supposed to be from home, children have to have radio, tv or internet in order to access the national curriculum, which is broadcast daily.

From Cusco, we first drove to Paruro, where Henry had planned to hold a second chocolatada on the same day. We dropped him off with one of the milk cans and 100 of the panettones at the elementary school in Paruro, then kept going to Mayubamba.

When we arrived, the people of Mayubamba already had a big cauldron of water boiling, ready for the chocolatada. When they saw the 30 liter milkcan, they ran to get a couple more pots, to take out some of the water so there was room to add the milk. It’s fresh milk, so they had to make sure to boil it before it could be served. We buy fresh milk because it’s more nutritious, supports local dairy farmers and comes in a metal milk can, so there is no trash from milk containers. To the boiling water and milk, we added three of the 1 kilo bricks of cacao, a bag of sugar, a handful of cloves and a stick of cinnamon the size of my arm.

All of the kids from the village were already there, so we lined them up, smallest to biggest to start giving out the clothes. It was pretty cute to see kids choose their favorite of the options available. It’s not always easy to judge the right size, but if the kid picks it out, I’m sure they’ll make it fit. After clothes was hot chocolate and panettone for everybody. After everybody had seconds on hot chocolate, we asked an adult representative from each household to line up for the rest of the donations.

The rice and oil seem pretty standard to me by now, so I was really happy to see the packs that Andrea had put together. From her hotel Maytaq Wasin, she donated six towels for each family. She has also been collecting donations, so she was also able to buy five bars of soap, four toothbrushes and toothpaste for each family. Hygiene is a real challenge when you live in an adobe home without plumbing and any help is appreciated. Andrea even included toothpaste for kids. Also, toothbrushes and toothpaste are not high on the priority list for families that are really struggling to get by. Few shops carry them and they’re just prohibitively expensive for most of the people of Mayubamba.

After we had handed out the food and packs from the hotel, we gave out some toys that David had collected from his students. Finally, we handed out the last of the panettones to anybody who had stuck around. It was a lot more than the village leaders were expecting and they were so happy. Before we left, the community president invited all of us for lunch, which was served in an empty classroom in the closed school.

Most communities are only able to share boiled corn or potatoes, which I am perfectly happy with! However, the mayor of Paruro had sent supplies to make chicken and potato soup with his assistants. He wasn’t able to be there today, but he certainly sent enough people to support us, including local police. It was cute to see the police helping the littlest kids who were having trouble carrying a mug of hot chocolate and the panettone and a granola bar, donated by the Maytaq Wasin.

The mayor also sent scarves and bags for those of us who came from Cusco. They’re from the Paruro artisans cooperative and are obviously made for the Cusco tourist souvenir market. Sadly, they have been sitting around for almost a year, since no tourists have been here to buy souvenirs. Tourism is starting to come back and I hope that the economy will revive. It’s starting very slowly, mostly with tourists from Lima. It may be several more months before people are able to travel from the US and Europe, where most of our tourists come from.

Microcuenca Ccarampa Chaiña

The Covid Relief Project took a chocolatada, food and warm children’s clothes to the five microcuenca of Ccarampa Chaiña. These families live hours from the nearest town and have no access to public transportation or health care.

I’m so excited that this is our first chocolatada! We went to see families from five “microcuenca” in the mountains about two hours from Calca. We have children’s clothes, 5kg bags of rice, vegetable oil and all of the ingredients for the traditional chocolatada. I’ve never before made hot chocolate in the kind of quantity that takes ten liters of milk, four kilos of pure cacao, two kilos of sugar, a cinnamon stick about two feet long and a whole cup of cloves. The communities have been instructed to have a huge pot of boiling water ready when we arrive and for everybody to bring their own cup.

Not only does asking people to bring their own cup save us from buying and making trash of hundreds of paper cups, it’s probably also better in terms of minimizing possible Covid spread. I’m always worried about the possibility of taking the virus from Cusco, where we have thousands of cases, to these isolated mountain communities that don’t have any. As I’ve written before, part of my worry is the actual virus spread, and part of my worry is that these communities don’t have any access to healthcare. They don’t have doctors or nurses or clinics or hospitals or even pharmacies. Many of them don’t have electricity or plumbing in their one room adobe houses. I try not to dwell on how devastating it would be.

Instead, I’m congratulating Henry & Auqui for finding the solution to our last logistics problem: the milk. We bought 16 kilos of pure cacao, 50 kilos of sugar, a kilo of giant cinnamon sticks and a kilo of cloves for the first three, maybe four chocolatadas. I didn’t want to buy dozens of 1 liter tetra paks of ultra-pasturized milk and certainly not cans of condensed milk. For Henry & Auqui to find a dairy who will sell us fresh milk solves all of those problems. We’ll transport the milk in reusable buckets, so there is no waste. Fresh milk is also much more nutritious and we’re supporting a local farmer. Win, win, win!

Today I met Auqui, Henry and Sarah at the Maytaq Wasin Hotel, which has become our staging ground for all of the December chocolatadas. Unfortunately, Henry was unable to come with us today because he has family obligations, though he promised me that he will definitely be there for the other four or five chocolatadas. Sarah is a friend from the US, who I know just because the expat community in Cusco is really small. Henry brought the mini-panettones directly from the bakery this morning, helped us load the truck, then had to go back home. Elio, who works in the mayor’s office in Calca, sent us a truck for all of the supplies, plus a pickup with an extended cab for us volunteers. We set out at exactly 6:30am, stopping just above Cusco to pick up Linda, who I know from the Healing House in Cusco.

It only took about an hour to drive to Calca, where we stopped for the vehicles to get gas and to pick up Elio. He has been working with Auqui to organize everything for today. We rely on local government to provide transportation for us and in some cases to notify the communities when we will be coming. Sometimes Auqui or Henry have direct contacts in the communities, but often we don’t. Many of the communities that we visit are chosen by the mayor’s office. We just call up the mayors and ask which communities in their area have not received any help since the pandemic began. There are so many tiny communities up in the mountains that there are always places that haven’t received even any help from the government.

Today’s families live in a collection of five “microcuenca” about two hours up into the mountains from the town of Calca. Collectively called Microcuenca Ccarampa Chaiña, the names of the microcuenca are: Ccachuchachu, Muñayoc, Marcani, Ttio 2B, Ttio and Airepampa. These communities are so small that they don’t have a mayor. Their only political representation is a community “president” who is supposed to advocate for them at the mayor’s office in what is effectively their county seat.

Our first stop was Ttio Grande. Ttio is pronounced differently from tio (uncle, in Spanish). Ttio starts with Quechua’s hard t, which doesn’t exist in Spanish or English pronunciation, although it is similar to the Arabic letter ﻁ. Likewise, the double c in Ccachuchachu is pronounced differently than the English or Spanish c. It’s harder, farther back in the throat and has a bit of a glottal stop to it. Quechua is very difficult to describe in writing, so I recommend listening to the interviews in Quechua that I’ve put on the Covid Relief Project’s YouTube channel.

It was raining lightly when we arrived, but kids were playing soccer and running around, clearly unfazed by the drizzle. There were a few adults in a corrugated metal structure on the side of the soccer field, who already had a giant pot of water boiling. We tossed in the cinnamon, cloves and bricks of cacao, then went back to the trucks to find the sugar and milk.

I was surprised that there were so few adults, but Elio explained that unfortunately there was a meeting already scheduled for today with elections for community president. Rather than count the place out, just because the adults wouldn’t be there, Elio decided that we would still take the opportunity to take a chocolatada and warm clothes for the children.

As our first chocolatada, we were a bit unorganized. Between May and August, we had gotten good at distributing food to one representative of each family and also managed distributing school supplies for kids. Chocolatada and clothes and food was a bit more challenging. We can’t give the clothes at the same time, because kids only have two hands. With a mug of hot chocolate and a mini-panettone, they didn’t have an extra hand for clothes.

Eventually, Auqui got everybody to sit down with their hot chocolate inside the shed (it was a big shed) and we started handing out clothes. I am not good at judging children’s sizes and because of the cold most kids were wearing several layers, likely wearing all of the clothes that they owned at the same time. Sarah, Linda and I did our best, then Auqui came to help after everybody had hot chocolate and panettone.

We couldn’t give out all of the clothes, since we still had one or two more stops. Even Elio wasn’t sure if the other communities would manage to gather in one place, or if we would be doing two more chocolatadas. We gave out the rice and oil to all of the adults present, though it was far less than we expected. As they say here “algo es algo,” something is something. At least we were able to take something for most of the kids, even if the adults didn’t all get what we had brought for them. There was a lot of hot chocolate left when we had to go, so the kids all got seconds and probably thirds after we were back on the road.

When we got to the second stop, Airepampa, Elio informed us that this would be the only other stop, so we handed over all of the remaining milk, sugar, cloves, cinnamon and bricks of cacao. This time we distributed the clothes first, which probably worked better. Some kids put them on immediately and some tucked them away in the layers they were already wearing. All of them made sure that they had two free hands for hot chocolate and panettone.

This community had prepared what they called “cariño” for us and invited us to enter one of the adobe buildings near where we had done the chocolatada. Sarah, Linda, Auqui and I were served boiled new crop potatoes and each of us a quarter of a roast guinea pig. As a vegetarian, I happily put my guinea pig piece on Auqui’s plate and stuck with the potatoes.

I complimented their choice of three of my favorite potato varieties: maqtillo, peruanita and compis. They apologized a bit, saying that the crop was very poor because the rains were a full two months late. Most of the potatoes that they had planted in August dried up and died before they could produce anything. The rains finally started this week, but for many farmers it was too little, too late. They also told us that their alpaca had suffered from the drought. Most of the alpaca who gave birth in the past two months had stillborns because they didn’t have enough grass to eat. Plants at this altitude are small and scarce, so when the rains didn’t start in mid-September, there was very little left for their alpaca to eat.

After lunch, I asked Auqui to interview Gregorio, the community president, and Elio. I’ll work on making a video of today’s event and post that on the Covid Relief Project YouTube channel asap. Before we left Airepampa, we distributed the rice and oil to every family, but still had a surprising amount left over. I was hoping that when we drove back through Ttio Grande we would be able to distribute more, but it started raining hard as soon as we were back on the road. When we got to Ttio Grande the rain was coming down in solid sheets and we didn’t see anybody outside. I’m a little sad that we didn’t distribute anything, since this is definitely one of the poorest communities that we’ve visited, if not the poorest. Still, this is the first of at least five chocolatadas, and I know that there are lots more needy families that we’ll see between now and Christmas. It’ll be okay to save what we have leftover for next Saturday.

Comunidad Campesina de Mayubamba

The Covid Relief Project took school supplies and food to the village of Mayubamba, about two hours from Cusco.

Arriving in Mayubamba

We left Cusco at about 8am on Saturday to drive to Mayubamba with all of the food donations and school supplies. Today’s team was the usual Henry, Auqui and I, plus Sonia Perkins, David Schmill and Steve Hirst. All six of us have been very careful to stay healthy and minimize any risk of taking Covid with us in any way. Mayubamba is very isolated and there are no cases of Covid in the area.

Communities all give us some short of welcome, but this time Mayor Villanota from Paruro had organized a real reception. There were the usual speeches, plus music, dancing and gifts. We certainly have never received gifts from any of these communities before. People are just too poor. Having the mayor there to organize such a big event was strange. It is not at all how we usually distribute food.

However, it has probably been months since the people of Mayubamba have had an excuse to get together for a happy event. Even in rural areas, people are very aware of the global pandemic, the numbers of people infected and dead in Peru, and how important it is for them to stay isolated from anybody outside of the community. I am acutely aware of the risk that we pose to them, coming from Cusco. We always keep our masks on, try to keep some distance, and wear gloves when we are giving food to people.

At Mayubamba, we also wore the traditional Andean hats that they gave us, along with the handwoven scarves and bags. With six of us, the scarves alone are worth about a fourth of what we spent on food for the village. If I had thought that the gifts came from the villagers themselves, I would have tried to pay them something. Knowing that they came from the mayor made me less uncomfortable. Still, they were expensive gifts that we definitely did not expect.

In every village they give us something. Usually it’s either boiled potatoes or boiled corn. We don’t expect people to be able to give us something, but we do appreciate being able to take the time to share with these communities. It’s the Andean version of breaking bread, and it builds a connection between those of us coming from Cusco and those who live in such isolated communities, hours from Cusco.

After the speeches and gifts, the mayor kept the music going as we first called up the 22 children under six years old to get their coloring book, colored pencils and carton of milk. All of the villagers were sitting on the soccer field where we had gathered, spread out a good six feet or more from each other. It’s hard to keep little kids from bunching up together, especially when they are approaching a group of strange adults. Still, the mayor did his best to keep the kids spread out a bit and there was also a community member there to spray alcohol on the hands of each kid after they received their gifts.

Next, we called up the 46 children over six for whom we had bought notebooks and three pens each. We also had bags of maná for all 68 children, with some extra. Maná is a sweet puffed corn, which is different from popcorn but a very popular treat here with kids. It is not made in the region of Mayubamba, so it was almost an exotic treat from the city for them.

After all the kids had something to do and something to eat, the mayor helped us call up a representative from each of the 76 families to receive the food donations. Each family received 5kg of rice, 2kg of sugar, 1 bag of salt, 1 liter of vegetable oil and four bags of oatmeal. They also received a package of ten small marmalades, donated by the MayTaq Wasin Hotel, in Cusco.

After all of the school supplies and food had been distributed, we were invited to try some roast potatoes. This is called huatia and they are roasted underground, below a huge fire. It is a very traditional way to roast potatoes, unchanged since before the Spanish arrived 500 years ago. All of the villagers who stayed were invited to share the huatia with us. There was a spicy ají sauce and fresh cheese to accompany the huatia. The mayor had also arranged for soup to be made for us and we sat down to share lunch together.

Finally, we had to go. We piled back in the van for the beautifully scenic drive back to Cusco. This is the sixth time that the Covid Relief Project has gone to take food to isolated communities since the pandemic started. It is always a humbling experience. The need is so great and we can only bring so much, but as they say here “cariño es cariño,” caring is caring.

Fundraising nitty-gritty

We raised $719.89 through PayPal, Venmo and GoFundMe. We also raised s/110 in cash. (s/ is the sign for Peruvian Soles). We withdrew s/1400 on August 20th, which cost $402.06. We withdrew s/1100 on August 22nd, which cost $318.80. That gave us s/2500 for $720.86, plus the extra s/110.

Purchasing and expenses

With 76 families, we had a budget of s/30 per family. For that s/30, we bought 5kg of rice, 2kg of sugar, 4 bags of oatmeal, 1 liter of vegetable oil and a bag of salt. That came to s/2,280 for food. We also spent s/264 on school supplies for 68 children. For the 22 children under six years old, we bought 22 boxes of colored pencils, 22 coloring books and 22 cartons of milk. For the 46 children over six years old, we bought 46 notebooks, 46 red pens, 46 blue pens and 46 black pens. We bought an extra 8 cartons of milk for pregnant women or new babies not on the list. The 30 cartons of milk cost s/90. We also spent s/42 on maná, which is a sweet puffed corn snack that is very popular with children here. We spent s/5 on disposable gloves to hand out the food and gave s/20 to the driver that helped us all day long.

All of that came to s/2,701. We only raised s/2610 for Mayubamba, but we had some money left over from last time, which covered the difference.

We also received 76 packages of 10 small marmalades from the Maytaq Wasin Hotel as a donation to take to the families. We are so thankful to the MayTaq Wasin for that sweet treat! Everything else was bought at Wagner’s, which is the wholesaler we have been working with since June.

Transportation Logistics

Auqui worked with Arturo Américo Córdoba Farfán at the mayor’s office in Paruro to arrange all of the transportation and to get information about Mayubamba. The mayor, Wilberth Villacorta Villacorta told us that Mayubamba is the poorest town in the district of Paruro and that 76 families there are in great need.

Mayor Villacorta sent a cargo truck and a van to Cusco on Saturday morning, to meet us at Wagner’s. We drove to Paruro, where the mayor and his entourage joined us, then on to Mayubamba together. The mayor brought several assistants with him, including Arturo and several municipal police.

At the end of the day, the cargo truck went back to Paruro and the van took the six of us back to Cusco.

Cusco to Mayubamba

We left Cusco in the morning with six of us in a van and all of the food and school supplies in a cargo truck. We met Mayor Wilberth Villacorta Villacorta in Paruro, then went together to Mayubamba.

In Quechua, Mayu means river and bamba is kind of like the word for town.

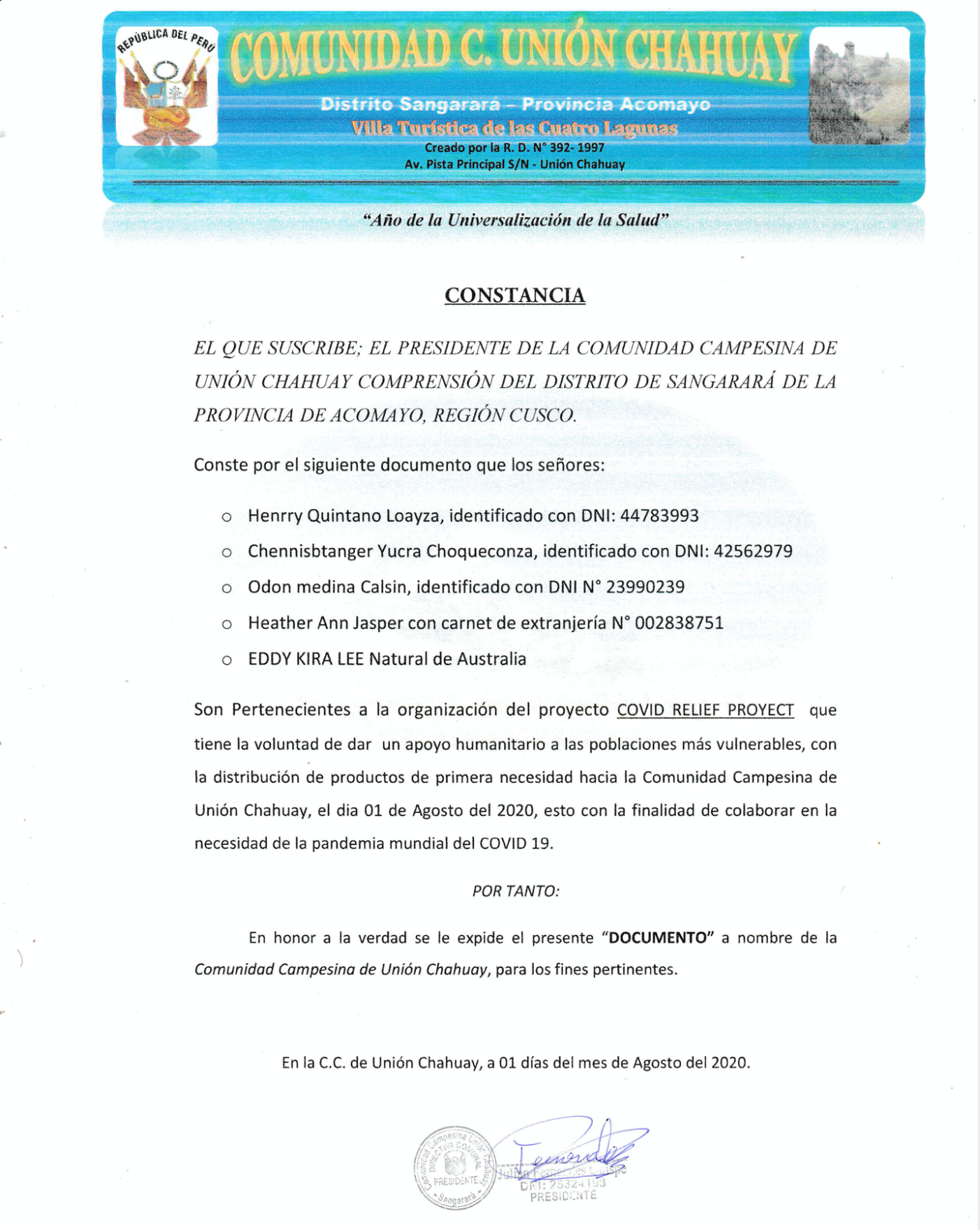

Comunidad Campesina de Chahuay

The Covid Relief Project took emergency food aid and school supplies to 90 families in need in the rural community of Chahuay.

About Chahuay

In the rural community of Chahuay, leader Lucio Quispe identified 90 families in need. Even though the pandemic has been ongoing for the past four and a half months, no government assistance has yet reached Chahuay. When we spoke to community members, they said that they feel forgotten and they think that it is because their community is so isolated and far from real towns that have services like banks, clinics and pharmacies.

Where they live is one of the most beautiful places that we have taken support to. They live on the shores of Lake Pomacanchi, a large lake, filling a wide valley. This area is home to the famous Four Lagoon Circuit, which used to be popular with tourists who wanted to see the beauty of the Andes, without the arduous treks required to see more mountainous lakes. They are at a higher altitude than Cusco, at 3,700 meters above sea level (over 12,000 feet). However, the valleys are wider, the mountains more gentle and there are roads throughout the area, so you can drive directly to each of the four lakes.

Obviously, with borders still closed and no tourists allowed to enter Peru, they have lost all of their jobs related to tourism. Nobody can get income from being tour guides, fishing guides, opening their houses for homestays or selling any of their artisanal products.

As with other communities, one of the reasons we need to take assistance to them is to help them stay isolated. There are no cases of Covid-19 in the area and if any of them leave the community to look for work in the city of Cusco or the mines, they risk exposure to the virus.

We are very careful to not take the virus with us when we visit these communities. We wear masks at all times, bring alcohol gel and this time we also brought disposable gloves. We used to just use alcohol gel, but with cases on the rise in Cusco, where we all live, we need to increase our caution and our safety protocols.

Going to Chahuay

Saturday, a van picked up Henry, Auqui and I, plus our friend Kyra Eddy, right at 8am, as they had promised. Kyra and her friend Justine, who lives in Australia, raised almost half of what we needed for today.

Kyra and I sat just behind the driver, with boxes piled between us. Henry and Auqui sat in the back, with as much social distancing as possible. We wore masks all day long, including in the van.

It took more than two hours to drive to Chahuay from Cusco. The town is on Lake Pomacanchi, in an incredibly beautiful setting. They had set up for us on the soccer field, which is near the lake. We set out the school supplies, and the food that we had purchased for each family. We also got out the maná, which came to 58 bags, once I put the four kilos into smaller bags. Maná is sweet puffed corn and is a very popular treat for children.

We called the kids first, oldest to youngest, to give them their notebooks and coloring books to keep them busy while we called the adults to come get their donations. The kids happily started eating their maná and coloring in their books as soon as they got back to sitting with their families. Even though we gave milk to the kids under two, we saw a couple older kids drinking straight from the cartons. I was just happy to see the kids smiling and sharing their school supplies and maná.

It took a while to get everybody on the list checked off, but it was only about noon when we were done. After the villagers all left, the community leaders brought out a couple tables and their family members brought food for us down to the soccer field. They served us plates piled high with boiled potatoes and onion salad, topped with a whole fried trout. Their lake is known for great fishing and it was the best trout I’ve had in a long time.

We ate with the community leaders by the lake and shared chicha. Most chicha is a lightly fermented corn drink. This chicha was made with barley, so it tasted a bit different, but was still delicious and refreshing. This chicha was also “frutillada” which means that they mixed in strawberry juice to sweeten the chicha.

Eventually, we had to leave and piled back in the van for the drive back to Cusco. Thankfully, we didn’t have any trouble with the police checkpoints and the driver took all of us home safely.

Logistics

We raised a fantastic $961.29, in large part due to Kyra, Eddy, an Australian kindergarten teacher who had planned to take this year off as a sabbatical to travel the world. She has been stuck in Cusco for the duration of the pandemic, so far. She donated herself, then told her friends back home about the Covid Relief Project. Her friend Justine Moorman started her own fundraiser for Chahuay and with her friends brought in a very generous $450 USD. This is about half of what we needed for Chahuay, which made a huge difference!

From the ATM in Cusco, we withdrew s/1400 Peruvian Soles on July 24, which cost $406.22; s/1400 on July 30, which cost $407.40 and s/500 on July 31, which cost $146.74. In all, we withdrew $960.36 and will save the extra $0.93 for next time.

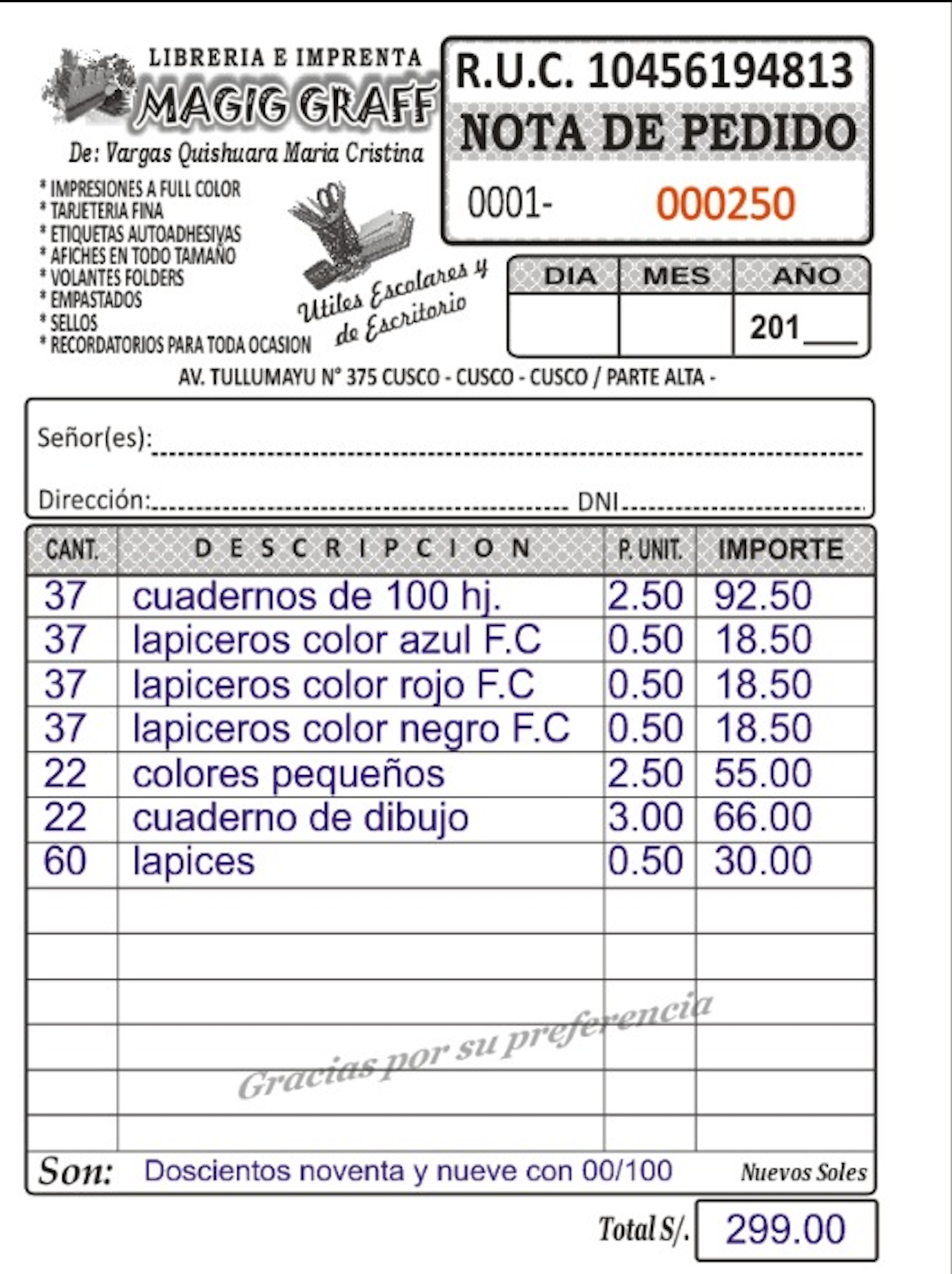

We spent s/2,700 on food for families, s/48 on milk, s/299 on school supplies, s/37 on four kilos of maná (sweet puffed rice) and s/10 on gloves for the team handing out food. Of the s/3,300 withdrawn, we have s/206 leftover for next time.

For each family, we bought 5 kg rice, 3kg sugar, 2 small bags of oatmeal, 1 package of soda crackers (each package contained six smaller packages) and 1 liter of vegetable oil. The wholesaler we work with, Wagner’s, helped us find which products they could get the best price on. They also donated 40 cartons of fruit juice, completely free for the families. Unfortunately, they didn’t have 90, but any help is welcome.

Due to the rising number of Covid-19 cases in Cusco, the government announced that many of the strict quarantine restrictions of April and May would return, starting on August 1st. This sent most of Cusco into a panic and we went to the police station on Friday night to ask if we would need special police permission for tomorrow - like we did in May and June. They assured us that tomorrow there wouldn’t be the same restrictions tomorrow as during the first part of the quarantine and that we wouldn’t have any trouble leaving Cusco - or coming home in the evening.

Still, the community leaders of Chahuay did not want to take any chances. They sent a truck to Wagner’s Friday night to take the food to the village, promising to send a van for us the next morning. Henry, Auqui and I sent to Wagner’s at 7pm to help load the truck and count the boxes to be sure that we knew how many to expect to have on Saturday morning.

Saturday morning, we had official paperwork for Henry, Auqui, Kyra and I. The van arrived right on time and we loaded up the school supplies and milk. There are 75 children under 14 in the families on the list. For the 16 children under 4 years old, we bought a carton of milk. For the 22 children 4 years old to 8 years old, we bought coloring books and boxes of colored pencils. For children 8-14, we bought 37 notebooks, 37 blue pens, 37 red pens and 37 black pens. We also bought 60 pencils, for all children over 4 years old.

It was wonderful to have some extra donations after we had enough to buy food for the families. We hope to be able to take school supplies for children again on our next donation day.

Comunidad Campesina Taray-Picol

The mayor of Pisac asked the Covid Relief Project to take food to the communities of Taray and Picol, because they have been hardest hit by the pandemic of any of the communities in the Pisac district.

Working our way along the Sacred Valley, the fourth mayor we contacted was in Pisac, who informed us that the two communities that need help the most are Taray and Picol. Taray is very close to Pisac and many families there worked with tourists, before the pandemic. Picol is farther from Pisac, but the mayor said that this was the poorest community in the Pisac district and that they really need help.

Just like the mayors of Yaurisque, Urubamba and Ollantaytambo, the mayor of Pisac sent a vehicle to Cusco Saturday morning to pick up the food and us. Every time, the transportation provided is different, but we don’t complain because the most important thing for us is that the mayor’s office cover the cost. That way we can spend 100% of donations on food.

Also like the last couple times, we bought the food at Wagner’s, where the owner Jorge has been very generous in our negotiations for what we can get for the amount of donations that we have. This time, we were working with a budget of s/30 Peruvian Soles (PEN) per family, which is about $8.60 USD. We paid s/14 for 5 kilos of rice, s/5.36 for a liter of vegetable oil for cooking, s/3 for a carton of UHT milk and with the remaining s/7.64 Jorge gave us nine small bags of oatmeal. These are usually at least s/1 each, so I was happy that he went up to nine, when he could have easily given us seven.

Today was the first time that Kerry Willoughby joined us and the other volunteers taking people food for the Covid Relief Project. Henry and Auqui, who have been working with me on the project for a couple months now were also there. It was a much bigger group than the previous three times, which was really fun. The more the merrier!

Kerry, Henry, Auqui & I met at Wagner’s in the morning, helped load everything into the van that was sent by the mayor of Pisac and hit the road. We drove to the main square of Taray, where we picked up Edy Pumamarca Dueñas, the community leader for Taray who had made us a list of 60 families in need. Then we drove to a road bordering the fields, where the families were waiting for us. It was a hot and dusty spot, but the people were so grateful that it was more than worth it.

After we had distributed the food to all of the families on the list, plus a few extra, one of the community members brought us a variety of white corn with giant kernels corn, called paraqay. The giant white kernels that are taken from the cob then boiled to make mote. Edy then invited us to his home where his mother served us an early lunch of boiled potatoes and cooked carrots before we left for the second village.

Picol is almost an hour drive from Pisac, up another very dusty road. At the entrance to the village there was a chain across the road, padlocked to a post. We waited for somebody to come let us in and used the handwashing station that they had placed next to the checkpoint. This is another one of those isolated communities that has no cases of Covid in the area and who are doing a good job of staying isolated enough to keep it that way.

We met with the gathered villagers and they brought us boiled potatoes and a spicy green chile sauce to share before we began the distribution. Despite all of the corn and potatoes that I had already eaten that morning, it wasn’t hard to eat a few more. They really are that good.

In Picol most of the assembled villagers were elderly. I was a little worried about them, since the pandemic has been so much more deadly for the elderly. In Taray, most of the people who came to receive their family’s food were in their 20s or 30s. Here, it appeared that all of the younger people were working in the fields.

Before we left, the people still came to give us more hugs than I expected - or than were probably safe. Despite being positive that none of us were sick, it was still a little unnerving to see elderly people from an isolated community come to hug a person from Cusco. Like T’astayoc and Perolniyoc two weeks ago, Picol does not have any access to a hospital, clinic or pharmacy. The community has a primary school, but no other services. If the virus did start to spread through their village, it would be devastating.

Still, I believe that we are doing more good than harm and that we have all been very careful to follow all Covid hygiene protocols. I know that tourists won’t be coming back anytime soon and we will likely be needed throughout 2020, if not partly into 2021. I want to keep taking food to people and hope that we can continue to do it in a way that keeps these isolated mountain villages free from the virus.

Comunidad Campesina de T’astayoc-Perolniyoc

We took food and children’s clothes to the communities of T’astayoc and Perolniyoc, which were chosen by the mayor of Ollantaytambo as the communities in the greatest need now. These families live high in the mountains, where they do not have any job opportunities besides subsistence farming. They used to be able to work with tourists trekking through the mountains, or go down to town to look for work. Since the Peruvian government closed the borders on March 15th, there are no tourists to work with. These isolated mountain communities do not have any cases of Covid in the area, so any trip down to town is a risk for bringing the virus back from places like Cusco, which has a high number of cases.

Our visits to the communities of T’astayoc and Perolniyoc were so humbling. The need is so great and we can only bring so much, but at least we’re bringing something.

We met the families of T’astayoc at a bend in the road, where three families live in their traditional stone houses with thatch roofs. We brought food for 35 families, 32 of whom hiked down to meet us. Some live as far as an hour higher up in the mountains, although most of the villagers live nearer the school, which is a half hour hike up from where we met.

Henry, Auqui and I were joined by Alfredo, who works for the mayor in Ollantaytambo. While a few community members helped us unload the truck, Alfredo gave out masks to anybody who didn’t have one. The villagers were seated in a big circle, not really as far apart as social distancing rules require, but none of them are a threat to each other. There are no cases of Covid near their community, so the only ones they really needed to keep a distance from were us.

Thanks to our generous donors, we had bought for each of the 35 families: 5 kilos of rice, 2 kilos of sugar, 2 tins of milk and 1 liter of vegetable oil. We had also used some donation money to buy bags of sweet popcorn for the children. Henry’s sister had donated animal crackers and some gently used children’s clothes.

Since the Peruvian government announced a mandatory quarantine on March 15th, these families have not had any work besides subsistence farming. Also, since there are cases of Covid in some of the larger towns in the area, like Cusco, few people from the mountains feel comfortable going down into town. Even if they had money to go shopping, it’s too dangerous to go buy clothes. These children likely haven’t had any new clothes since Christmas, although in six months any child will have outgrown their clothes. When markets open up in Cusco, we plan to buy more used children’s clothes to take with us on each event.

After we distributed the food and clothes, we sat down in the circle with everybody else to share the boiled new crop potatoes that they had brought for us. They passed me a big basket of potatoes and joked that they wanted to see me eat all of them. I took several, then passed the basket on. They were each about golf ball sized, but all different colors. There were deep purple ones, red ones with white middles, bright yellow ones and others with a purple outside but bright pink inside. Like most freshly harvested vegetables, they were delicious! One family had also brought a bright yellow spicy pepper sauce to pour on them, which was equally delicious.

We were sitting near a beautiful sparkling stream, which one community leader informed us was the only water source for the villagers. They have been asking the government to dig a well for years, but still have not had any success. We promised to advocate for them in all of our future dealings with the mayor’s office. We would have loved to stay longer, but had to go back to Ollantaytambo to load the pickup again for the drive up to the village of Perolniyoc.

On to Perolniyoc!

When we arrived at Perolniyoc, we saw that the families had gathered at a basketball court. It was jarring to see an expanse of cement, surrounded by a chain link fence, after the bucolic charm of T’astayoc. Still, it was the most convenient gathering place where we could get the pickups. Each family sent a representative, who hiked down a half hour or more from where they lived in the mountains. Like the families of T’astayoc, the people of Perolniyoc have been reduced to subsistence farming, without any contact with the outside world. There are no cases of Covid in the area and they have made their own checkpoint at a river crossing, near the main road.

Thankfully, the woman working the checkpoint was expecting us and unlocked the gate at the bridge. The people of Perolniyoc have made a strong metal gate to protect themselves from any unauthorized visitors. We gave the woman at the checkpoint one of the extra 5kg bags of rice and thanked her for letting us pass. She welcomed us, although we are coming from Cusco, where the numbers of Covid cases are starting to spike as the government is now easing some of the restriction of quarantine.

Community president Delfina helped us organize the distribution, with one woman helping Henry and Auqui handing out the food while another called names from the list. After we distributed the rice, sugar, milk and oil, we called all of the kids to come over. We handed out the last of the popcorn, animal crackers and donated clothes. As solemn as many of the adults had been, the children ran around laughing and playing. They tried on each other’s new clothes and traded animal crackers.

Delfina invited us to a house nearby where a woman makes chicha and sells food from her home. We were treated to big glasses of refreshing chicha, which is brewed from corn. It is one of the most obvious links between the modern Quechua and the ancient Inca civilization. Recipes have been passed down through the generations and I have no doubt that what we were served is exactly like what the Inca used to drink.

We were also served plates heaping with rice and pasta cooked with vegetables, topped with a fried egg. It was simple but delicious and we were so grateful, since breakfast had been over seven hours earlier and we didn’t have time to eat more than a few potatoes before we had to leave the families of T’astayoc.

After lunch, we drove back down to the checkpoint, which was unlocked for us again. Back at the main road, one empty pickup turned left to go back to Ollantaytambo and our driver turned right, to take us back to Cusco.

The logistics and backstory

We did our shopping again with Jorge Wagner, who runs the wholesale store Wagner’s Licoreria. Like last time, he was very generous when I was negotiating for prices of 5kg bags of rice, 2kg bags of sugar and vegetable oil. When we had first spoken about getting supplies for June 27th, he was unsure about being able to get oatmeal. I even asked at a few other wholesalers to see if they had any oatmeal in stock. Every single one of them said that they couldn't get it because it’s an imported product and they were all out of imported products.

Last time I had bought the 3 Ositos brand (3 Little Bears), which is the most popular brand. This time, nobody had any oatmeal of any brand. It really is considered a treat here and we are so fortunate that we were able to buy 5 kilos each for the families of Sut’uc-Pacchaq. We didn’t have enough donations to buy the large tin of powdered milk that we got for the June 6th event, but after some negotiations, we settled on two cans of condensed milk per family. With a few last minute donations, we were able to pay for two cans of milk for a hundred families.

We are dependent on the mayors of each town to provide transportation, and this time turned out to be much more complicated than the first two times. The mayor of Ollantaytambo sent a truck to pick up the food Friday afternoon, rather than Saturday morning. Henry, Auqui and I were offered places to stay in Ollantaytambo Friday night, plus dinner and breakfast the next morning.

When we got to Ollantaytambo, we unloaded all of the cargo into Town Hall, then the mayor took us out for dinner. There is a little restaurant hidden back behind several shops, just across the street from Town Hall. Technically, restaurants in Peru are only allowed to operate for take out and delivery. However, Town Hall employees and the local police have an arrangement with this restaurant, which is still not open to the public.

After dinner we were taken to a hostel nearby. Walking through the main square, and along the streets leading from it, was a surreal experience. We’ve gotten used to Cusco’s empty streets, but had never before seen Ollantaytambo during quarantine. It felt as eerie as the first time I ventured out into the empty Cusco streets back in March.

Like Cusco, Ollantaytambo is a very touristy town. It’s the gateway between the Sacred Valley and Machu Picchu, so it obviously gets a lot of traffic. The mayor said it’s been unnaturally quiet the past three and a half months and they can’t wait until tourism revives.

The next morning, we packed food and children’s clothes for the 35 families of T’astayoc in one pickup and drove up to meet them. It was about an hour and a half drive from Ollantaytambo. After the distribution, when we went back to Ollantaytambo for the rest of the food. We filled the backs of two pickups for the drive up a parallel valley to Perolniyoc. These two communities were chosen by the mayor of Ollantaytambo as being the two in the greatest need.

Comunidad Campesina de Sut’uc-Pacchaq

The community of Sut’uc-Pacchaq is a two hour walk from where the road ends at the Inca archeological site of Chupin. Sut’uc-Pacchaq was chosen by the mayor of Urubamba as the area in greatest need. Fifty families were chosen by local community leaders as those most in need now. The few people in these communities who used to have jobs outside the community worked as horsemen, taking their pack horses on treks through the Lares valleys. With the hard stop in tourism, as a result of Covid-19, there are no more treks and therefore no more need of their skills or their horses. Everybody in the area is back to being a subsistence farmer, with some in more dire straits than others.

Today we took food to the communities of Sut’uc-Pacchaq, which are a two hour walk from the nearest road. We had been in communication with the mayor of Urubamba, looking for a community who truly needed help now. The government has been sending some financial assistance to vulnerable families during the quarantine and state of emergency, but it is far from adequate.