Mt. Ausangate

If you’re coming to Peru you need my travel guide app. Peru’s Best is the only app you need to plan a trip to Peru. Download Peru’s Best for iPhone or Android!

Day 1, November 24, 2020

The Ausangate trek started at 4am today! Well, the drive to the trailhead started at about 4am. We didn’t actually start walking until about 10am. The drive from Cusco to Ocongate is over 3 hours. We had breakfast in Ocongate and bought a few last minute supplies.

Another half hour up a dirt road and we stopped where our arrieros were already getting the horses ready. Arriero is usually translated as horseman, the person who owns and cares for the horses on a trek. Rather than the usual backpack trip that I grew up with in the US, when you carry everything in your backpack, including your tent, sleeping bag, food and clothes, we had opted for what tourists in Peru normally do: hire porters or horses.

It seems extravagant, compared with the backpacking trips I did with my parents. However, when organizing this trip for my friends and I, there were several good reasons to hire two cooks and two arrieros. First, none of these four men have had any paying work in 2020. Pandemic and quarantine hit right at the end of the rainy season, when tourists should have been coming back to Peru. Few people work in January or February and they count on working almost every day in June, July and August. These months are not only the dry season, they’re summer vacation in the northern hemisphere, where most of our tourists come from. Due to the pandemic, nobody had worked at all during what should have been the normal tourist season.

Second, though everybody in the group has been living for months in Cusco, at 11,000 feet, we were planning to hike and camp at about 14,000 ft, with several passes at well over 16,000 ft and the highest pass at just over 17,000 feet above sea level. No matter how acclimatized you are, 17,000 feet is high, and it’s best to have as light a backpack as possible.

Third, it’s so nice to get to camp and have the tents set up and lunch or dinner ready and waiting. Maybe that part of hiring four people is a bit extravagant, but we all definitely appreciated it. Our cook was named Gabriel and he brought an assistant named Richard. Both of them are from villages near the town of Ollantaytambo. Our arriero was Pancho and he brought an assistant named Pablo. They are both from the rural area near the trailhead.

So, this morning, as Pancho and Pablo packed the food and camping gear on our horses, we organized our daypacks and got ready to start hiking. Today was an easy day, mostly a warm up to get us used to being up at 14,000 feet. We only hiked about four hours, then had both lunch and dinner at the campsite.

After lunch, most of the group went to soak their feet in the hot springs that literally boil out of the earth only a few minutes walk from camp. I stayed to help Auqui do a Pachamama ceremony for Sonia and David. Actually, the ceremony was for David’s close friend Keiko, who died two years ago, yesterday. Keiko was Peruvian and the reason that Sonia and David came to Peru in the first place. Therefore, Keiko is also the reason that Sonia and David have been trapped in Peru the past eight months of quarantine and closed borders.

A Pachamama ceremony involves creating a bundle of offerings, called a despacho, that are either burned or buried, fertilizing the Pachamama, which can be loosely translated as Mother Earth. The best of what the Pachamama provides for people is sacrificed to be included in the offering. This includes fruit and natural sweets. It may seem odd to some people that oranges, chocolate and caramel would be things to sacrifice, but for me those are some of the best things that the earth provides and therefore a real sacrifice to give them back. Also included are coca leaves and animals. Coca leaves are sacred for all kinds of things and an absolute necessity for any offering. Real animals aren’t sacrificed anymore and instead are represented by animal crackers and a chunk of lard, which should be from a llama rather than a pig.

The Pachamama also likes port, which can be replaced with red wine if necessary. Auqui had brought a bottle of port and red and white carnations, plus several kinds of incense to burn, including myrrh. There is a specific order to what is added to the offering, starting with a square of natural cotton and the fruit in the middle. The flowers and coca leaves frame the offering, covering the cotton and forming a square, which is filled piece by piece with everything being offered to the Pachamama. After participating in several ceremonies, I can follow the order but don’t know any of the prayers associated with each item, since they’re in Quechua. Ceremonies like this were changed very little by Spanish influence and are a direct link between modern Quechua people and their Incan ancestors.

After the ceremony had concluded, Pancho dug a hole for the despacho, which we buried not far from camp. We opted for burying, rather burning partly because we were so far above treeline that we would have had to pack in the firewood on the horses. Also, Keiko died and was buried in Vietnam. Burying the despacho was symbolic of him finally having a burial in his home country. His family was from Lima, so he probably never came to Ausangate, but it’s such a sacred mountain, called Apu in Quechua, that it seemed appropriate anyway.

Dinner was served almost immediately after the ceremony, as always starting with soup. At altitude, hot liquids are needed as often as possible. Lunch and dinner always start with soup and breakfast always includes a pitcher of maca or quinoa drink. We all crashed immediately after dinner, tired not from hiking, but exhausted from the early morning, the cold and the change in altitude. At 14,000 feet, it is always cold, year round.

Day 2

Today we woke up to a deep blue sky and as soon as the sun reached the camp, we warmed up quickly. Gabriel made us a hearty breakfast of scrambled eggs, fried plantains, toast, coffee, maca and a hard boiled egg to either eat for breakfast or take with us as a snack on the trail. We packed our backpacks as light as possible, leaving almost everything for Pancho to load on the pack horses.

Our first destination was Upis Cocha, a lake less than an hour from camp. The campsite last night was named Upis and cocha just means lake in Quechua. It was beautiful, with shallow areas near the shore frozen over and mini ice bergs dotted across the lake. All of yesterday, and most of today, we were approaching Mt. Ausangate from the north, the direction of Cusco, and the face of the mountain we saw was the exact same angle and face that you see from Cusco.

This was a much longer day than yesterday and as we approached the mountain, we started to veer off to the west, starting our counter clockwise loop around the main peak. Mt. Ausangate is part of a massive section of the Andes, so though we were hiking almost 360° around the main peak, we were surrounded by other peaks for most of the four days.

We hiked about four hours before lunch, then another four hours afterwards. Our campsite was just below a beautiful lake and Auqui did another Pachamama ceremony for us before dinner. I asked for safe passage around the mountain, for nobody to get hurt and for the rainy season to start on Wednesday - when we are back in Cusco.

Day 3

After another hearty breakfast, we started from camp up to the highest pass of the trek. Palomany Pass is at 5,200 meters, which is just over 17,000 feet above sea level. It’s definitely the highest I’ve walked to, though I was at over 17,000 feet in 2013 on a road trip near Arequipa.

I am so thankful that not only did we have perfect weather, I felt really good. I didn’t feel any of the usual altitude sickness symptoms of headache or nausea. I didn’t even feel tired and made it to the top a good 10 to 15 minutes before anybody else. I had time to take photos with my camera, selfies with my phone and eat some chocolate before the rest of the group joined me.

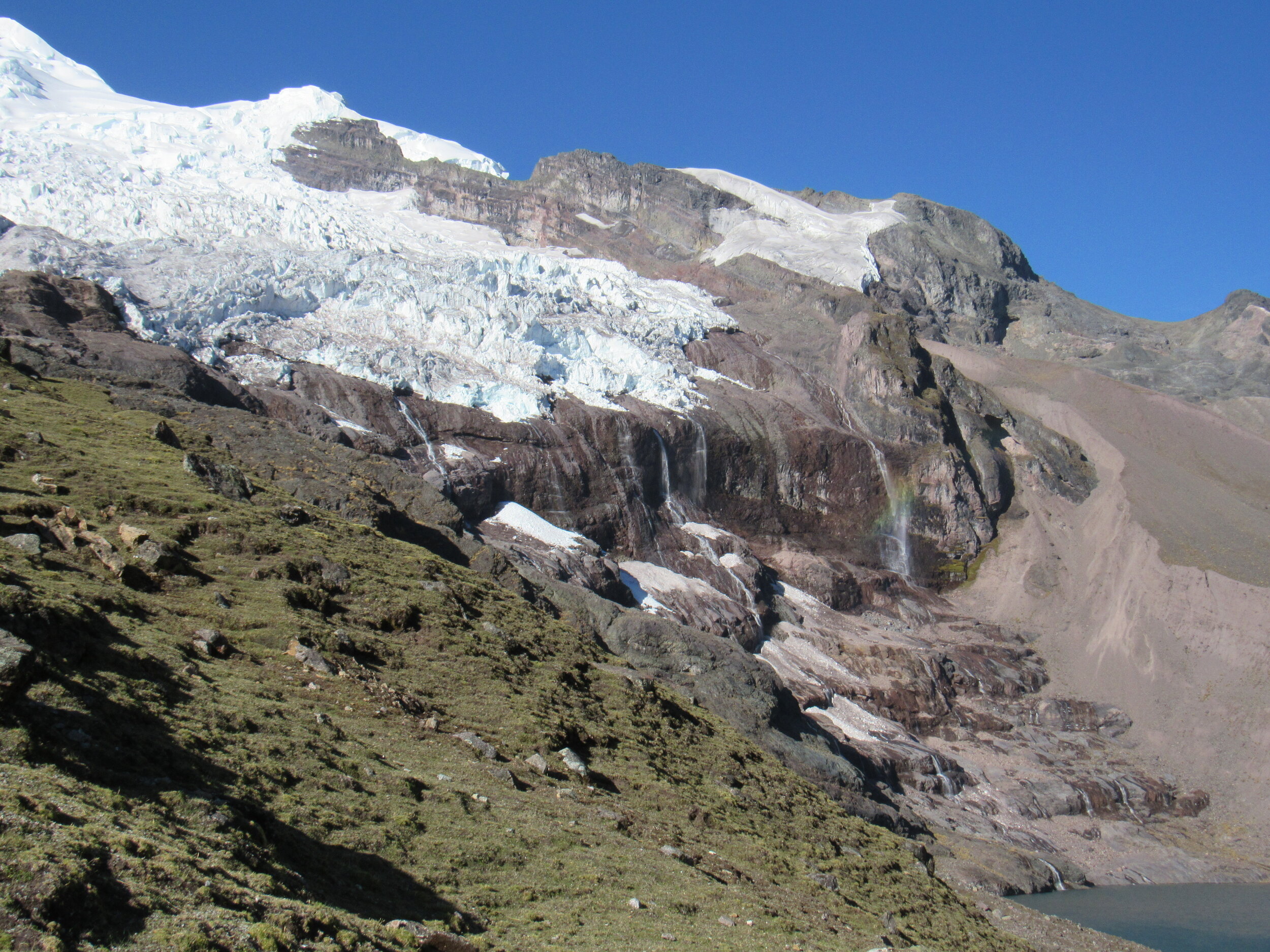

The sun is so strong at that altitude - especially so close to the equator. With no clouds and no wind, it actually felt warm up there, though that altitude is almost always very cold. We were higher than some parts of the glacier, which we could see on both sides of the pass. My only regret is that two other people in the group saw a vicuña, but I missed it.

Vicuña are a protected wild species of camelids. They’re related to llama and alpaca, but have much shorter fur and are all a light brown color, similar to a deer. Both llama and alpaca come in several shades of brown; everything from white to black. Vicuña grow a big puffy pompom of white fur on their chest, which is one of the softest furs in the world. It’s similar in softness to chinchilla or rabbit, though it is much warmer. Vicuña also are adorable because they all have giant eyes, like babies.

We didn’t actually see any other vicuña on the trip, probably for two reasons. First, they are illegally hunted and their population is declining, despite being both protected by the government and considered sacred in traditional Andean beliefs. Second, this is the time of year when they are legally gathered by indigenous Quechua families to harvest the fur. They are not hunted or trapped, but rather bunched together by long lines of people clapping and singing. It’s a beautiful tradition, called chaccu, that goes back hundreds of years before the Spanish invasion. Now, government regulations require veterinarians to be present both to check the wild animals for disease and in case any are injured in the process.

Even though I felt great in the morning, an hour before lunchtime I was ready to lay on my back, with my feet up on my backpack and not walk anymore. After we left Palomany Pass, we descended to a beautiful lake named Surococha. I saw a condor, lots of vizcachas and a few horses, but no vicuña or puma. After Surococha, we walked through wide meadows in a classically U shaped glacial valley. It was a completely different landscape than the bare slopes of stone up near the pass.

After lunch is kind of a blur. I know that we walked another five hours, which felt like ten. Since we circled the peak counter clockwise, my left ankle got very tired of always being the uphill ankle. The trail after lunch was uneven, with lots of loose rocks, since mostly we were following dozens of interconnected alpaca trails that crisscross the mountainside. Since we were walking on the east side of the mountain, that late in the afternoon the sun was on the opposite side and we were walking in shadow. It got very cold, very quickly, and I was happy to have my down jacket, hat and mittens in my backpack. Thankfully, the weather stayed clear and we didn’t even have much wind to deal with. Dinner was ready when we got to camp and I crashed almost immediately after dinner. I was probably asleep around 8:00.

Day 4

We were all so tired last night that we all fell asleep early, which meant that most of us were up and enjoying a hot cup of coca tea as soon as the sunlight hit our tents at about 5:30. Nobody seemed particularly tired, even after how far we hiked yesterday, probably because we were all very motivated to get to the hot springs at Pacchanta (the double c means that you pronounce it pac-chanta).

The trail today was a gentle downhill, getting increasingly closer to habitation. We started seeing older women sitting on the side of the trail, knitting and waiting for us. As the first group to hike the four day loop since the pandemic started, I was surprised that they were there. I asked Auqui if they knew that we were coming and he said that word spreads fast in the mountains. Somebody saw our camp being set up last night and probably the word spread down the valley.

Most tourists are happy to buy souvenirs directly from the people who make them. Buying a scarf or decorative weaving from the woman who raised the alpaca, sheared the wool, spun the yarn and knit the item is true fair trade in my book. Unfortunately, everybody in our group has lived in Cusco long enough that we all have baby alpaca scarves and more bracelets than we can wear. I did buy a small blanket, which is incredibly intricately woven but beyond a few bracelets, nobody else bought anything from any of the women along the trail.

We had prepared for this though, and had school supplies to give to them, as well as dried fruit and nuts. All of these items are very difficult to buy for people living so high in the mountains. Even if we weren’t going to buy anything, at least we could give them something to help in such difficult times.

We also asked them how their children were getting education this year. In March, the president of Peru, who until recently was Martin Vizcarra, declared that for the 2020 academic year, all students and all teachers would stay home. Not even everybody in cities in Peru has access to the internet, so the national curriculum is accessible online but also broadcast on national public tv channels and radio stations. This high up in the mountains, there aren’t even any radio signals, and the children have to hike down an hour or two to get somewhere that has a radio signal.

One of the children also told us that since so many families don’t have radio signal or access to tv, that the teachers in the area had organized a rotation so that every child went to school once every two weeks. The teachers would give each student the assignments printed out and collect all of the assignments completed in the past two weeks. I don’t know how students who struggle with the work can possibly get enough help with this system, but it’s better than nothing. At least they are doing everything they can to both keep school going somewhat and to protect these isolated families from getting Covid.

As I’ve written before, none of these families have any access to a pharmacy, government clinic or hospital. The closest town, Ocongate, is five hours walking and another hour on motorcycle or horse from some of these families. There is a small government clinic, but no hospital in Ocongate, and any seriously ill patients would have to be evacuated to Cusco, another four hours by windy mountain road. There are still no cases of Covid in the area we were hiking in and we really can’t let it spread up there.

It was only about four hours of walking slowly, taking photos and stopping to talk with people to get to Pacchanta. We arrived before Gabriel had our lunch ready, so we got drinks and sat in the sun, next to the stream that we had been walking along all morning, since we left camp. We were back on the north side of the mountain and again had the same view that we have from Cusco. Of course, the mountain was much closer and more impressive than when you see it in the distance, looking south from Cusco.

After lunch we soaked in the hot springs and enjoyed our last up close views of Ausangate. There is a cold stream next to the hot springs, so you can hop out and cool off easily. There are at least six pools (I really should have counted) and the caretaker can add more cool water to any of them, if needed. The pools aren’t very big and they seem to assign each group their own pool. In a celebratory mood, we even bought some beer, now that we were back down to about 14,000 feet and in a town that has a road to it. It always impresses me how quickly the human body can adapt to high altitude. Pacchanta actually felt lower to me, after four days hiking at higher altitude.

Eventually we had to put back on our filthy hiking clothes and get in the van. Since we were trying to pack light, I had clean socks and underwear for after the hot springs, but didn’t bring an extra shirt. I wore the same pair of pants all four days and was very much looking forward to having clean clothes to put on the next day.

Everybody else probably was too, but when the van rolled into Cusco, four hours later, we all flinched at the bright lights and loud city noises. I also saw everybody staring at the people in the streets, who of course were wearing masks. Ausangate is so remote that we had actually escaped the global pandemic and it was a shock to find ourselves back in pandemic life again. Cities always feel too loud and too bright after I’ve been in the mountains for several days, but I’ve never come back to a pandemic before and I did feel sad, facing reality again. Like always, I started calculating when I could get out of town again for an extended period of time.