Tingana Nature Preserve

I only got out of the boat once - to climb up in the top of a giant ficus tree.

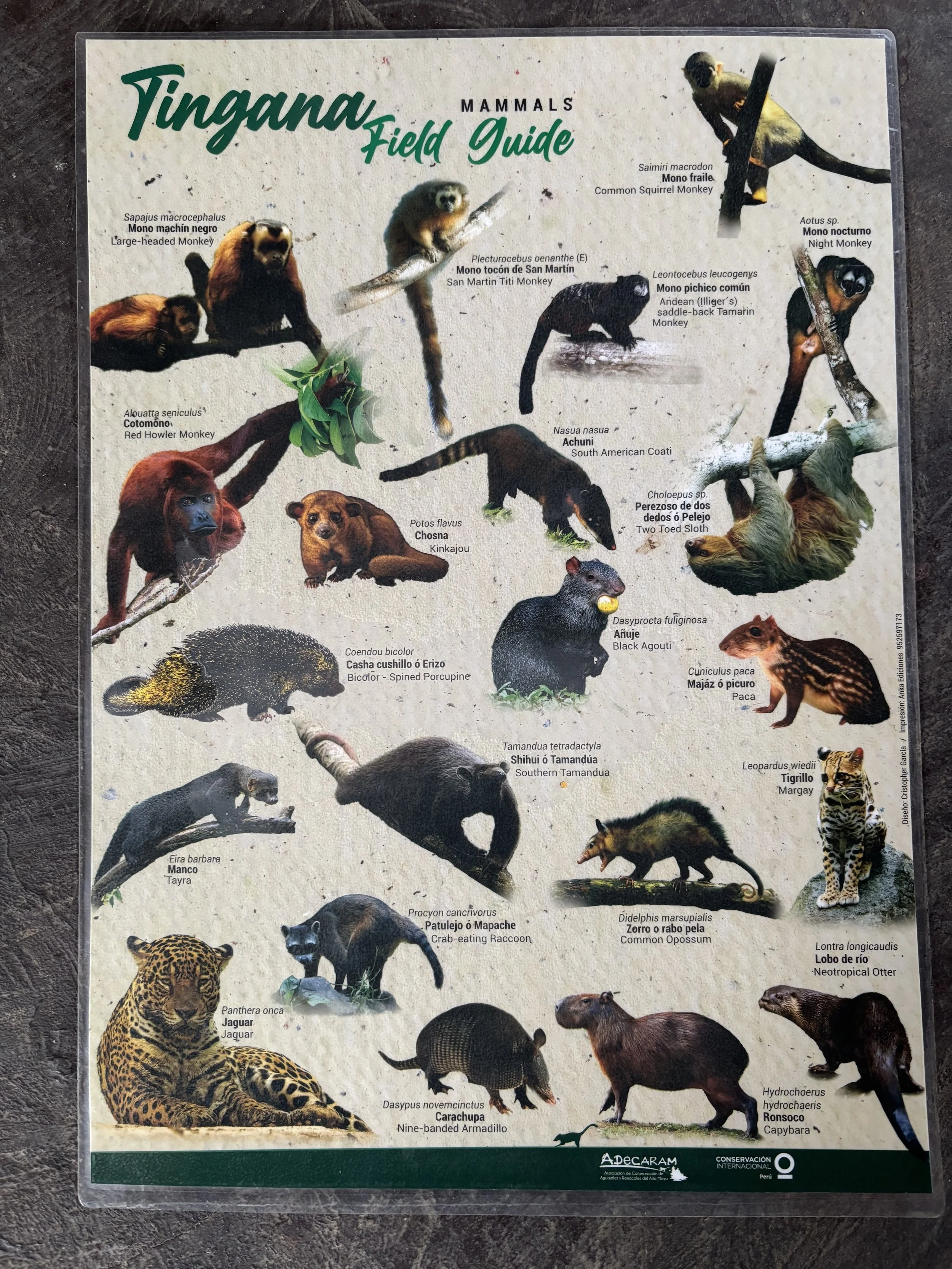

Wildlife at Tingana

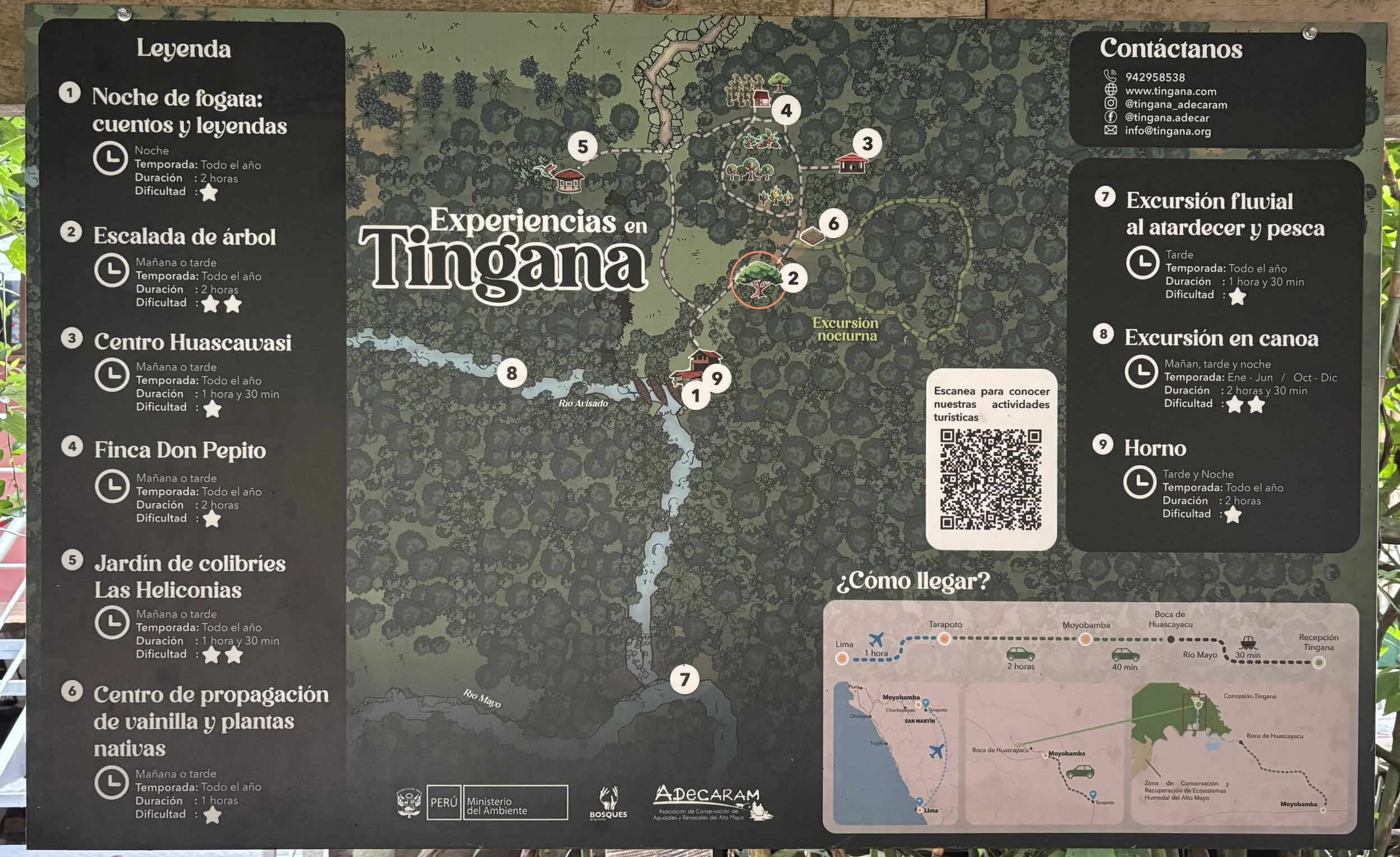

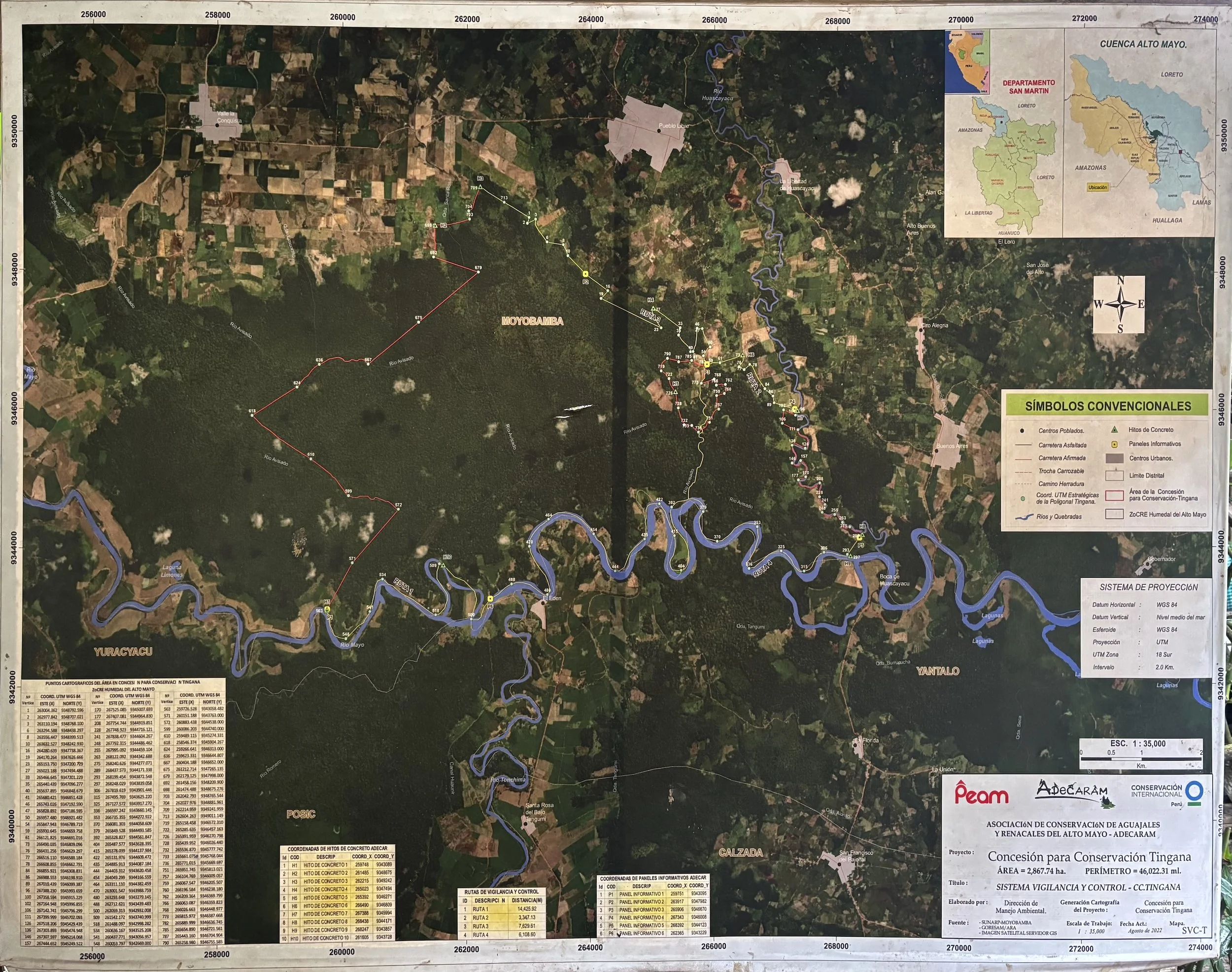

La Tingana is a 3,000 hectare (7,413 acre) nature reserve, protected by the Tingana community. One of the community members, who told me he goes by Anderson, said that they used to have 300,000 hectares, but most of it has been stolen for rice farming, the natural habitat destroyed. They are determined to hang on to what they have left, and visiting is one of the best ways to support their conservation efforts.

They have registered 226 species of birds, 39 mammals and over 50 species of fish.

It’s about an hour drive from Moyobamba, then half an hour in a motorboat to the lodge. They picked me up at 6am, so when I arrived at the lodge, they served me breakfast and then we set off. La Tingana doesn’t have the kind of expert bird guides that Ikam does, but they still know a lot of birds and definitely know every little creek in their reserve. From the lodge, we headed upstream in a shallow wooden boat, with my guide paddling in the front and Anderson paddling in the back. I frequently had to duck under overhanging branches, laden with orchids, bromeliads and other epiphytes.

I heard a lot of birds

It was a dark morning, menacing rain, so most birds were already hiding, waiting for the storm. I heard more birds than I saw, but my guide was pretty good at identifying most of them for me. Also, with the low light most of my bird photos are blurry dark silhouettes, except for the trogons above. I was happy to see four species of kingfishers, even if my photos are terrible. The only one I haven’t seen now is the Pygmy Kingfisher, obviously the tiniest of the kingfishers.

However, the monkeys were very active, trying to eat as much as they could before the storm broke. I saw a few Howler Monkeys and Capuchin Monkeys (above), but dozens of Squirrel Monkeys (below). They all ignored us, except for one Squirrel Monkey that was crossing some branches above us just before the rain started. It looked down at us, grabbed the branches with all four feet – and tail – and shook them hard, showering us with leaves and chattering what could have been a warning. Less than a minute later, rain poured down in sheets.

I also saw a sloth, curled into a ball and sleeping, and a family of coatis. Coatis are in the same family as raccoons and have a ringed tail, but that’s about where the resemblance ends. Coatis have a much longer snout and less fur, probably because they live in a much warmer climate than most raccoons. I’ve seen them before in Mexico and Costa Rica, but this was my first time seeing them in Peru and the first time seeing them in trees.

There was at least a dozen in a tree far above the stream, that I initially assumed were monkeys. When my guide told me that they were coatis, it was immediately obvious from their tails. Monkeys don’t stick their tails up in the air like coatis. We stayed for a while to watch and at one point they all started coming closer, then apparently noticed us and scampered back up to higher branches.

One of the bird calls I can recognize is the loud, echoing whistle of a White-throated Toucan. I’ve seen them at Los Amigos Research Station and other jungle spots, but this time I didn’t see it. When we heard it, my guide told me that local people believe that the toucan warns that rain is coming. Just a few minutes later, the monkey shook the branches above us, and it started pouring. (I’ve heard it on sunny days too, but it’s usually going to rain in the rainforest, so they’re not wrong).

Anderson, boat captain

Anderson grew up at La Tingana, like his parents and grandparents before him. He was a wealth of information about the land and its animals.

We paddled back to the lodge, since it was about lunch time anyway. I remember it being delicious as I had requested vegetarian and was impressed with the cook, but I didn’t take a photo and now I can’t remember what it was. By the time I’d finished with lunch, it had mostly stopped raining and it was time for the last part of the tour.

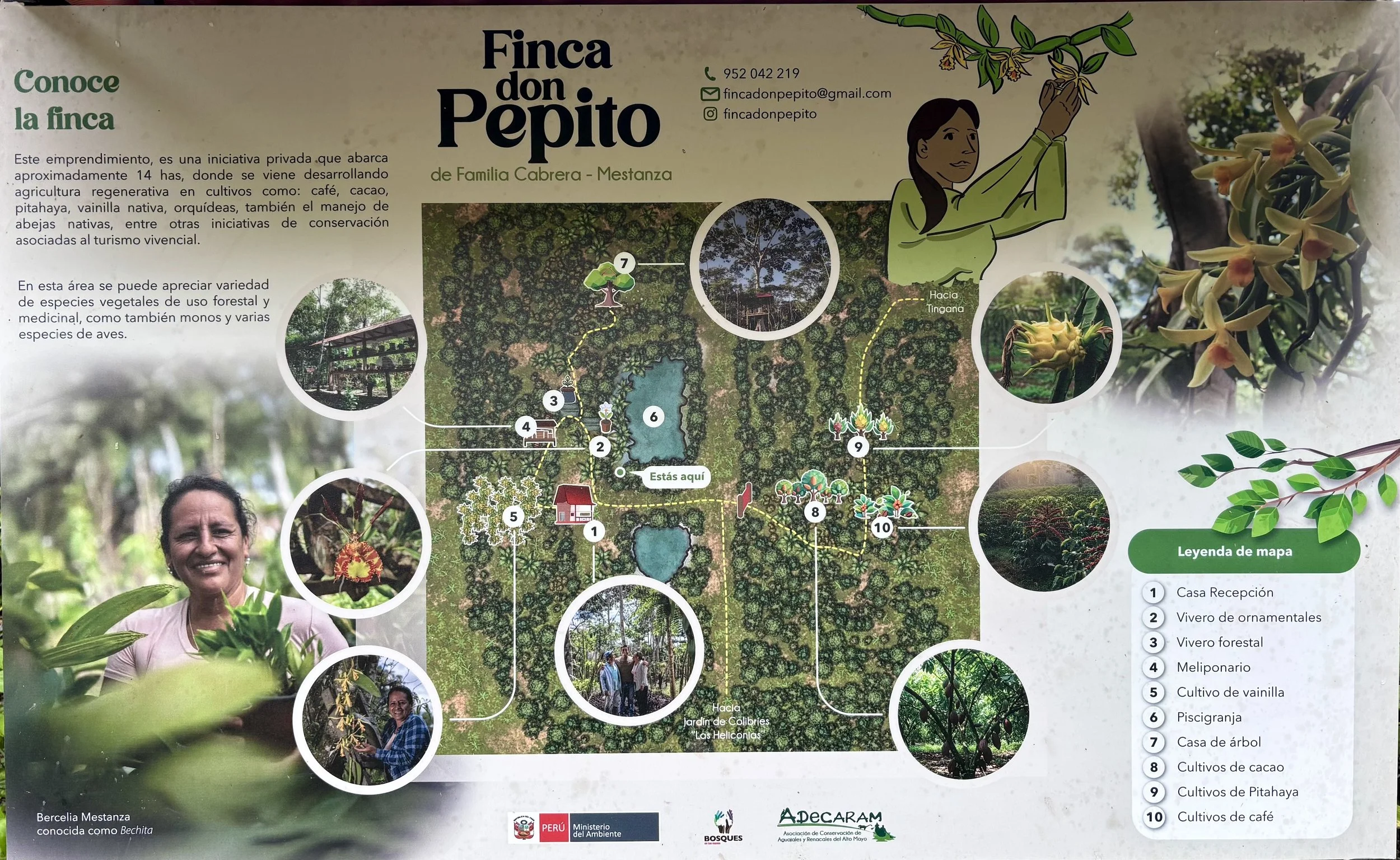

Finca Don Pepito

My next activity was visiting a nearby farm called Finca Don Pepito. I met Bercelia Mestanza, known as Bechita. She showed me where they grow coffee, cacao (for chocolate), pithaya (similar to dragon fruit), and a variety of vanilla that’s native to this part of the Peruvian rainforest.

I had no idea that vanilla was an orchid.

I also didn’t know that vanilla is always pollinated by hand, as the few insects that pollinate it are very inefficient. Bechita told me that she pollinates about 300 flowers a day and that if she didn’t maybe a dozen of those flowers would be pollinated naturally. She has over 5,000 vanilla orchids, many of them flowering every day. She has some volunteers at the farm, but most of the work is all her.

Just as complicated is trying to dry the vanilla beans in a rainforest. Bechita has a greenhouse full of plastic tubs, designed to heat up enough to dry out.

She also has bee hives for several native species of rainforest bees. All the boxes in the photo on the right are bee hives, including the stump in the middle on the bottom. They’re tiny and she collects their honey, which is highly prized by people who know honey, but they make it in very small quantities. You can see below some of it is sold in droppers. Her son makes soap with local ingredients like vanilla, cacao, aloe and more.

Contact Bechita on Instagram or Facebook or email her fincadonpepito@gmail.com to volunteer here!

Follow La Tingana on Instagram or Facebook and check out their website!

There are new cabins at the lodge where I had breakfast and lunch. They have programs for 1-3 nights but I bet you could stay as long as you wanted. Especially if you want to see all five of Peru’s species of kingfishers, you should stay until you’ve seen them all. I saw all of them except for the Pygmy Kingfisher, which apparently is usually spotted in the evening.