Unu Raymi

The Unu Raymi Water Festival is one of the most modern Inca festivals I’ve ever seen.

The Unu Raymi Water Festival is held at the Llanquepata Inca terraces near Sangarará, about two hours from Cusco. In Quechua, Unu means water and Raymi is a party or festival.

The sweetest water

Llanquepata has six springs, three of which have been developed into the source of drinking water in Sangarará. The others flow into ancient irrigation channels that feed nearby crops and a trout pond. It’s pure, sweet water and the reason why Sangarará is the only place in Peru where I drink the tap water without boiling or filtering it.

The Inca knew it was some of the best water in the Cusco region too. That’s why Llanquepata was where ceremonies were performed to thank the Pachamama (Mother Earth) for water. The Inca and his entourage would have traveled two or three days from Cusco to visit Llanquepata for the ceremonies. The terraces were so well built that they haven’t needed any restoration in the past six centuries. What you see in these photos is original.

New ancient traditions

That history is why I was surprised to learn that 2024 was the third annual Unu Raymi. Before the pandemic, there were plans to start a new celebration at Llanquepata, but the first one wasn’t held until 2022. The townspeople picked March 22 as the date because it’s UNESCO’s World Water Day. This is a modern ceremony done according to ancient Andean traditions.

The mayor of Sangarará

Mayor José Luis Salazar and all the town hall employees dressed in their ceremonial attire for the celebration.

Sangarara’s six ayllus

An ayllu is a group of families who live near each other and are often linked by marriages. Today, it seems more like a neighborhood association, but the ayllu was one way that the Inca organized their subjects.

Sangarará’s ayllus are named Manakollanayuq, Sullqabe, Llabe, Supamarca, Alaylla and Pallpa. My friends, the Sandoval Quispe family, belong to the first ayllu. I met this family in 2021, in Cusco. Though they maintain their family home in Sangarará, the younger generations have moved to Cusco. Only their mother, Virginia, lives fulltime in Sangarará.

Ayllus arriving

The six ayllus of Sangarará each arrived at Llanquepata from a different place.

A day of festivities for the people

The whole day seemed to me like the mayor had put on a show to entertain his constituents. They all dressed up in their traditional outfits and lined up on the terraces to watch the Inca and Qoya perform the ceremony. When the Inca left, they broke out picnic lunches and sat on the surrounding hills and terraces to watch the dance competition. It was like the whole village dressed up to go to the theater and the play was followed by groups who came to dance for them. Besides the dancers, I was the only person not from Sangarará.

Coca leaves have been sacred since pre-Inca times. No ceremony is complete without them.

The Inca and the Qoya

The Inca was the name of the ruler, not the people. Today many people use the world Inca to refer to commoners, when the Inca ruled most of South America, the people were referred to by the places they were from. The Qoya was the Inca’s wife. Nivardo Carrillo was hired to be the Inca for the ceremony. (I’m still trying to find out the name of the Qoya, as I wasn’t able to talk to her).

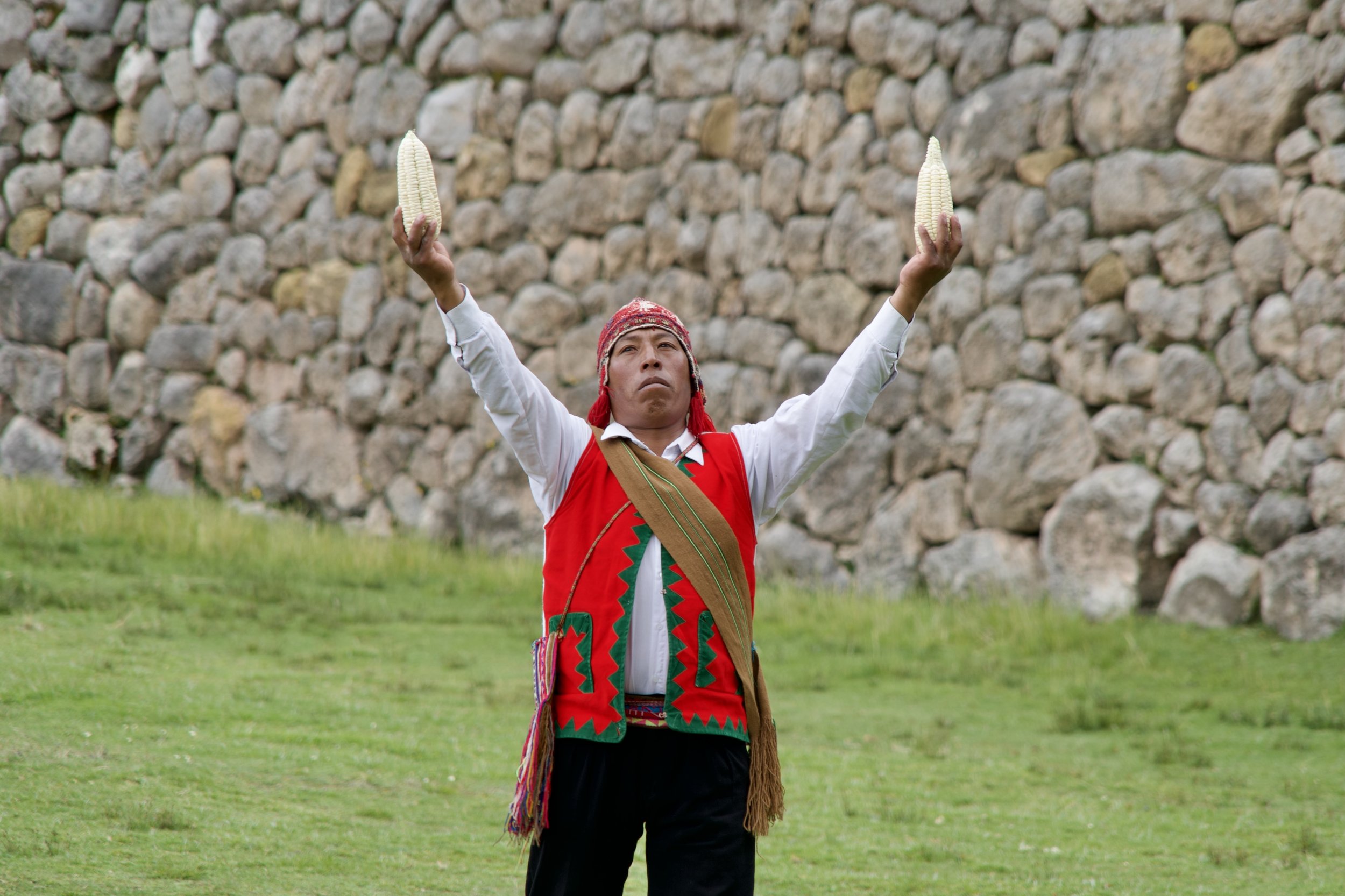

Sacrificing chicha

Chicha is a lightly fermented corn drink and is essential for ceremonies. There were endless cups of chicha for me and the other attendees. We always poured a bit on the ground for the Pachamama before drinking from the cup.

The Pacco arriving

The pacco is an Andean shaman. He arrives with fire to burn the offerings that each ayllu bring him.

The sacrifice

Each ayllu brought an offering of corn, potatoes, chicha, coca leaves, flowers, and oca (a spicy root vegetable) to add to the sacrifice bundle. While the Inca and Qoya did their part of the ceremony, the pacco added the offerings to the bundle and wrapped it in a special cloth. Since this was a modern Inca ceremony, the Inca gave the bundle to the mayor to be given back to the pacco to be burned. There were a lot of prayers and speeches that I didn’t understand because everything was in Quechua. Embarrassingly, I still only know a few words of Quechua.

The fuel that was piled up and lit to burn the offerings was dried llama and alpaca poo. Sangarará is at 3,763 meters (12,346ft) above sea level. It’s not a place where trees grow well and like many places high above treeline, the best fuel is processed grass. The little pellets of llama poo are mixed with water and straw, then dried in clumps that can be used as fuel.

Fire and Water

The pacco leaves with an empty basket, all the offerings to water have gone up in smoke.

The musicians

Before and during the ceremony with the Inca, various bands played at a set of microphones next to a pile of amps that you could hear miles away. The first bands all used traditional Andean drums, flutes, the conch shell blown like a horn and rattles of llama hoofs. Once the dance competition started, there were much more modern instruments.

Live bands

I lost count of how many bands played that day. The Inca had his, each dance troupe had their own and others played between events.

All the way from Puno

This was the only dance troupe not from the Cusco region and the only one whose musicians didn’t use the mics and amps.

The mayor dancing

By the end of the day, the mayor was still dancing, even after the dance competition and ceremony ended.

Virginia Sandoval Quispe

Virginia and her son Rodolfo invited me to join them to see her represent her ayllu at Unu Raymi.