Having Covid in Cusco

After more than a year writing about other people having Covid in Cusco, I now have the opportunity to write about the pandemic from a much more personal point of view.

After writing for almost a year about other people having Covid, I now have the opportunity to give a first person account of having Covid in Cusco. Thankfully, I had a very mild case. I had a fever for two days and a slight cough the third day after the fever was gone. Unfortunately, the person who brought it to my home was so sick that I had to play nurse for about a week, before a family member could come get him. I’ve done the contact tracing, which goes from my houseguest-turned-patient to his family, who live in a small town in the Sacred Valley.

When I first realized that this was probably Covid, I found a list online of places in Cusco that supposedly can test for Covid. Of the 57 places listed, I called about a dozen, of which only two could do a rapid test. None of the ones I called could do the more thorough, and more accurate, molecular test. My first test came back negative, though the clinic told me to come back in a week to do the test again, since it has a high rate of false negatives. A week later I tested positive for both the IgM and IgG antibodies.

The body first produces the IgM antibodies, as an early immune system response to an infection. The clinic technician explained that the presence of IgM mean that the infection is ongoing and that I am still contagious. The IgG antibodies take longer to form and provide a longer lasting protection against the infection. I was told to come back for a third test, in another week, to check if I still have IgM antibodies. Until then, I should consider myself highly contagious and must stay home. The streets are not patrolled by military and police like they were back in April and May, but some police are assigned to enforce mandatory quarantines.

The positive Covid test brought a lot more paperwork than the previous negative test. All of a sudden, the technicians were very interested in knowing exactly where I live, asking for descriptions of the house on top of the actual address. They also had to fill out a form for contact tracing. I was asked if I had had any contact with somebody with Covid and who they were. I gave the names of my houseguest and his sister, the healthcare worker who was the first person in their family house to get sick. I was surprised that I wasn’t asked for their addresses or phone numbers, or any way to get in contact with them. Instead, I was instructed to ask them to get another Covid test. I was also told to contact Diresa, the Dirección Regional de Salud, and report myself.

Each Covid test cost me s/100, which is less than $30, but that’s a lot for most people here. That can be food for a whole week for a family of five in the city, or a month’s budget for a family in the countryside. Calling around to testing centers, most charged more than s/100. So far, I’m in for s/200, plus everything I’ve spent on cough syrup, cough drops and ibuprofen for the fever and headaches. Few Cusqueñans would pay another s/100 to be told that I’m not contagious anymore. While the French woman has been documented, the other two people I got this from have not had a positive test. By that logic, the number of people with Covid in Cusco is probably double the official numbers. If testing was free, that would be a different story.

The positive Covid test also brought a new anxiety: would I be able to travel in three weeks? In order to get on a plane from Cusco to Lima, and now also to enter the US, I need a negative Covid test. Since the only rapid test here is for antibodies, I won’t be able to get a negative test again. The molecular test takes longer and since the test must be done within 72 hours of leaving, I might not be able to get that back in time. One of my parents’ friends had this problem on a flight to Hawai’i. Her results didn’t come back in time for the flight, so she rerouted through Portland, where you can get a rapid test in the airport.

Absent a negative test, I need medical clearance to be able to fly. That means, in the next three weeks before my flights from Cusco to Lima to Mexico City to Seattle to Boise, I need to fully recover and get a doctor’s note that I’m fully recovered. If I recover any slower than that, or have trouble navigating the red tape here to get the clearance, I won’t be able to travel. Rather than be anxious for the next two or three weeks about if I’ll be able to get medical clearance in time, I decided to postpone the trip. When I do reschedule, I will probably be a lot less anxious traveling, since I’ll be armed with antibodies. Even better, my parents will have the vaccine by then. They have an appointment for the first shot on January 29th, which seems to me like record time for Idaho. If I have antibodies and they have been vaccinated, my trip there will be much less stressful.

Meanwhile, there is another person with Covid in this story, and this one is my fault. Recently arrived from France, she had hired me to give her private classes in both English and Spanish. All arrivals from Europe in January were required to stay in their lodging for a two week quarantine, until the government shut down flights from Europe entirely. The entire world is freaking out about the new Covid variants in England, Brazil and South Africa, triggering more border closures around the globe.

I wore my mask for my first two classes with her, nervous about her having recently arrived from Paris. I didn’t ask her to wear a mask and she didn’t seem at all interested in wearing one. She mostly stayed in her AirBnb, but did leave sometimes to buy food. As far as I know, I was the only person who visited her. So, as far as people I could have infected, at least she’s somebody without any friends or close contacts with here, and unlikely to continue to infect more people.

Unfortunately for her, the AirBnb owner figured out that she was sick and asked her to leave. This landed her in a hotel, since she didn’t have the energy to find an apartment or even another AirBnb. At the hotel, she was reported to authorities, who gave her a Covid test, which of course was positive. A local doctor was assigned to her, who visited her at the hotel and lent her a pulse oximeter, to check her blood oxygen saturation every two hours.

Having enough oxygen in Cusco can be a struggle in the best of times. At over 11,000 feet, it is common for new arrivals to be short of breath and to have blood oxygen levels of 80% or even lower. I also borrowed a pulse oximeter and was thankful to see my level was 94%, though the houseguest-turned-patient hovered just under 80%. This is a person who is from Cusco and who should be up in the high 90s. I wanted to send him to the hospital, but he was against it, so I asked a family member to come get him. The next morning, his niece came with a taxi to take him to a sibling who lives here in Cusco. He was far too sick for a drive to the Sacred Valley, even though his village is really only an hour away.

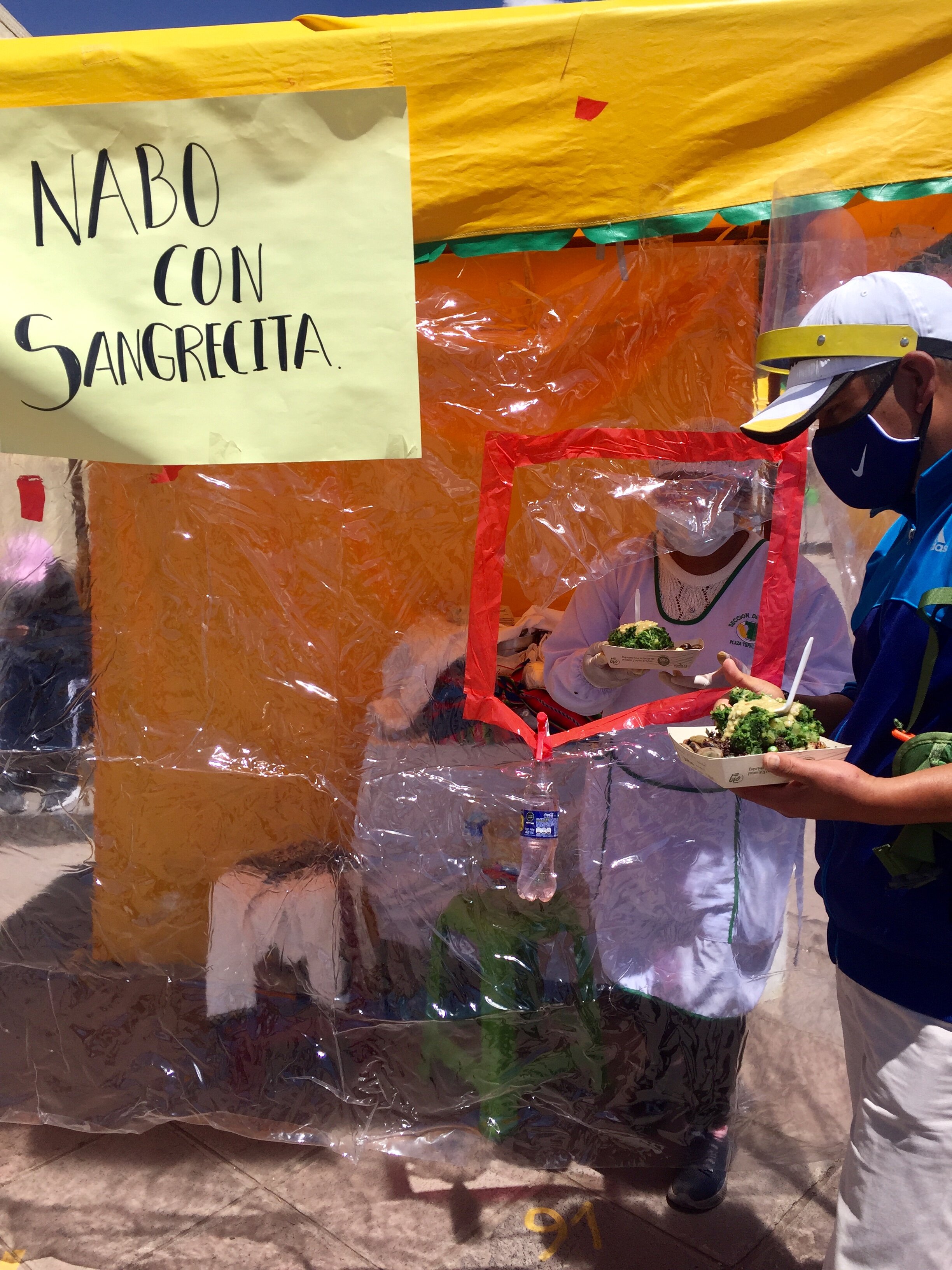

While he was in my care, I received a constant barrage of recommendations and medicine from various family members. One niece came with honey and navo, which is like a large radish. She hollowed out the navo and filled it with honey, instructing me to have him drink it in five hours. One sibling brought the antibiotic azithromycin, which just made him nauseous and gave him diarrhea. He only took one pill, then agreed with me that antibiotics weren’t going to help. In the absence of a positive Covid test, I had counseled him that even the regular flu was caused by a virus and that antibiotics couldn’t do anything about a virus. Even more worrisome, another sibling brought him a bottle of Ivermectin drops. He was told to take half the bottle one day and the other half the next. The package insert said nothing about Covid but instead referenced administering it to animals.

On a preliminary online search, I found that Ivermectin is used to treat parasites in animals. The FDA website answered the question “Should I take Ivermectin to prevent or treat Covid-19?” with the response “No. While there are approved uses for ivermectin in people and animals, it is not approved for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.” The article goes on to state that Ivermectin is approved for humans for “some parasitic worms” and that “Ivermectin is FDA-approved for use in animals for prevention of heartworm disease in some small animal species.” I recommended that he not try the Ivermectin and instead try a recipe from yet another sibling who had told him to finely dice red onion, garlic and ginger and put them raw in honey to soak for several hours, then take by the spoonful as a cough syrup. I figured that couldn’t hurt him.

Once I finally had my apartment to myself, I set about marshaling my friends to help keep me inside. Kerry got me fruit from the market and took my clothes to the laundromat. Steve got me cough drops at the pharmacy. David brought vegetables and cough syrup. Sonia brought oranges and a cinnamon roll. Andrea lent me three books and brought some chocolate chip cookies. I felt very well taken care of and had very few symptoms. Then I lost my sense of smell and taste. It was the strangest sensation. My mouth felt kind of numb, like the numbing effect of Szechuan peppercorns. If you haven’t had Szechuan peppercorns, think about how right after you brush your teeth, all you can taste is toothpaste. It kind of numbs your taste so that if you eat something immediately afterwards, you can’t really taste it.

I had been sick for over a week when it happened. First, some oranges that Kerry had brought seemed bland. I figured she had gotten ripped off. Then the mint tea that Sonia gave me didn’t have any flavor. Then I put a lot of garlic and ginger in my broccoli stirfry for lunch and that’s when I figured it out. The problem was not the oranges or the mint, it was Covid.

We’ve been hearing about this odd symptom since March. When the global news started to cover the pandemic in March, it was cited as a quirky Covid symptom and one that didn’t actually cause any harm. When testing was rare or non-existent, it was a way to know that you didn’t have the regular flu. For the curious, if I eat a raw garlic clove, I can taste that. I haven’t tried raw chili peppers yet.

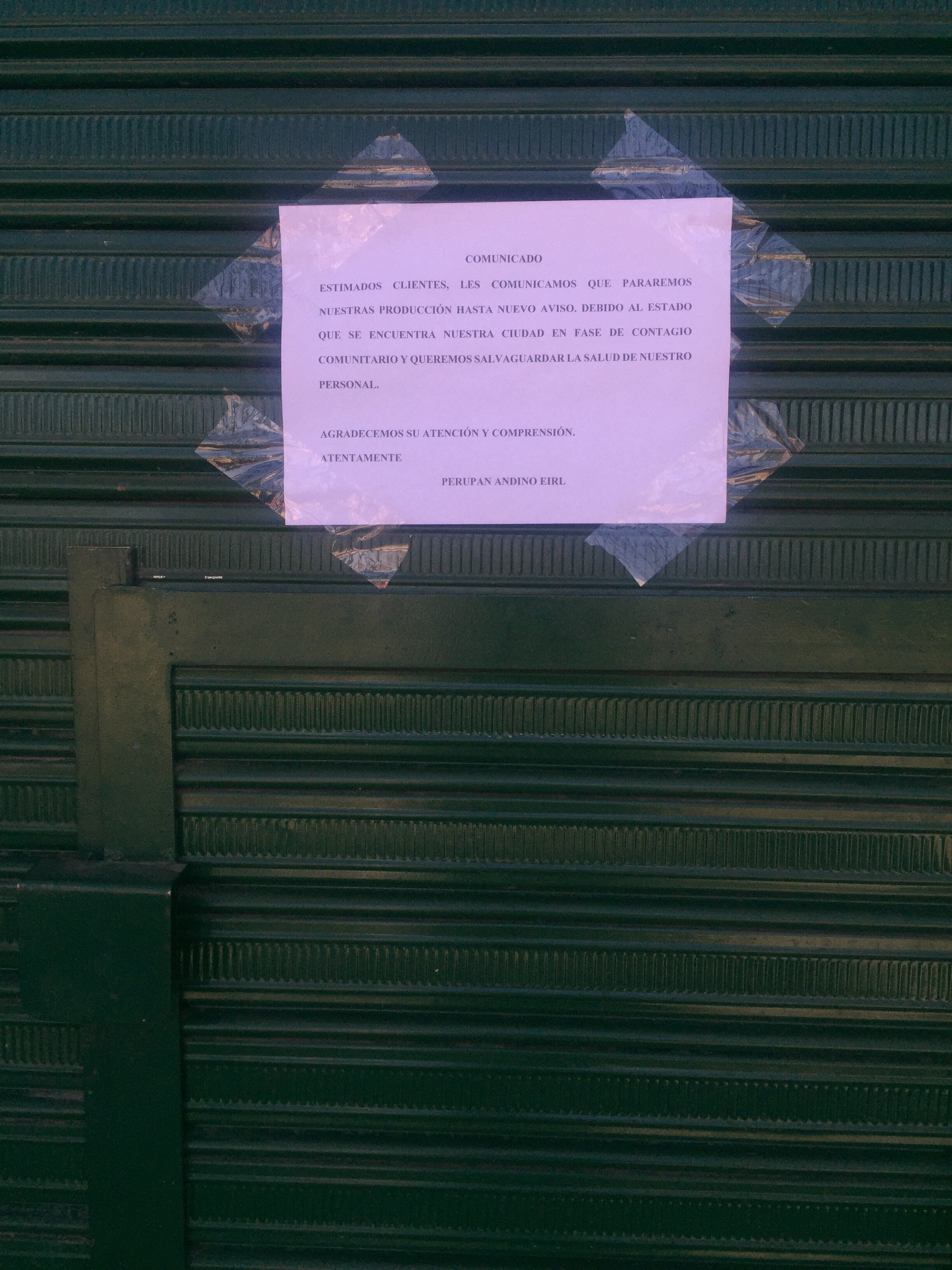

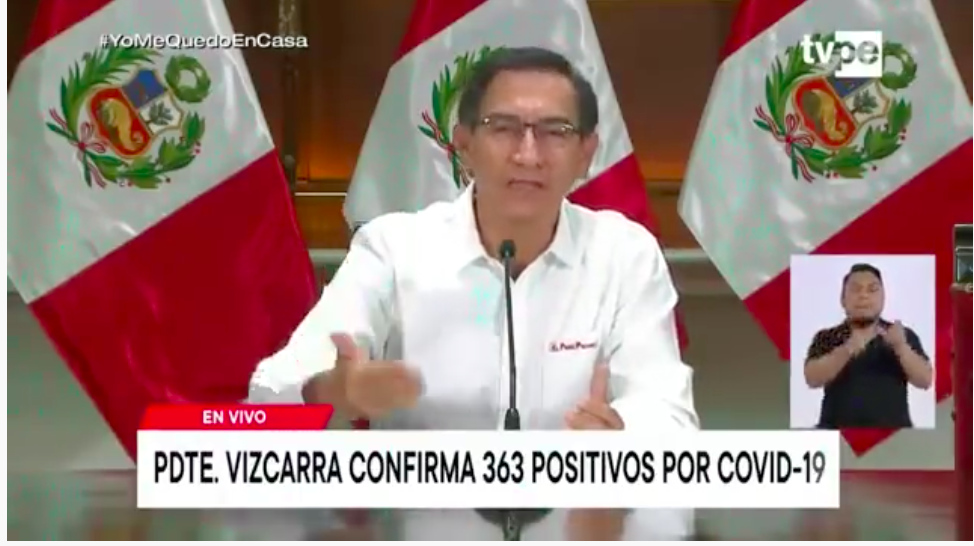

When we look back to then, it’s amazing how optimistic we were that this wouldn’t last very long. A few weeks probably, a couple months at the most. Over the 41 weeks that I blogged about the pandemic in Cusco, my tone goes from annoyed at having to stay inside, to surprised that this is going on so long, to excited that I’m living such a historic moment in Peru to resigned and bored. I went from obsessively reading all of the emails from the US Embassy in Lima to not checking my email for days at a time. I went from planning how tourism could be revolutionised to completely apathetic about the tourism industry. I started out listening to every address made by the Peruvian President Martin Vizcarra, often playing the YouTube version repeatedly as I did my own translation and transcription of his speeches for my blog. When he was deposed with a “constitutional” coup, I didn’t bother to listen to either of his replacements’ speeches.

In May I was so fired up about creating the Covid Relief Project and taking food to isolated mountain villages, that needed to stay isolated to avoid a Covid outbreak. By August I was worn out on fundraising and increasingly scared about taking Covid from Cusco to any of these villages. None of the eight we had visited had any Covid cases in the area and I was terrified of the consequences of taking the virus there. None had any access to healthcare, whether that be hospital, government clinic or even pharmacy. Several didn’t have electricity or running water in any of the homes. I rallied for December and raised enough money for another six villages but was so relieved to call the project done after the last village on January 6th. I just didn’t have it in me to keep going.

Looking back over my blogs, I’m reminded of my 2014 blog “Goodbye Bangladesh,” written six months after I had left the country. Sometimes I need some space, some time, before I’m ready to reflect on an experience. The pandemic has now gone on for so long that I want to reflect on it, except that we’re still in it. Early on when I heard people say that we were “in the middle of a global pandemic,” I would remind them that we were still at the beginning of a global pandemic. Now that we have several approved vaccines, are we in the middle yet? I’m certainly in the middle of my own Covid infection. With numbers of cases still rising around the world, can we say that we’re in the middle? Or perhaps past the middle? Could we be closer to the end?

I wish I knew the answer to that question. I wish I could write a blog counting down, instead of continually counting up. This is week 46 since Covid-19 was first diagnosed in Cusco and since the start of the quarantine and lockdown in Peru. Once we hit 2021 I just couldn’t keep up the same weekly blog. It felt too endless. It still feels endless and I’m still wishing that I could start some sort of countdown. I wish I knew when Cusco would be able to get back to normal.

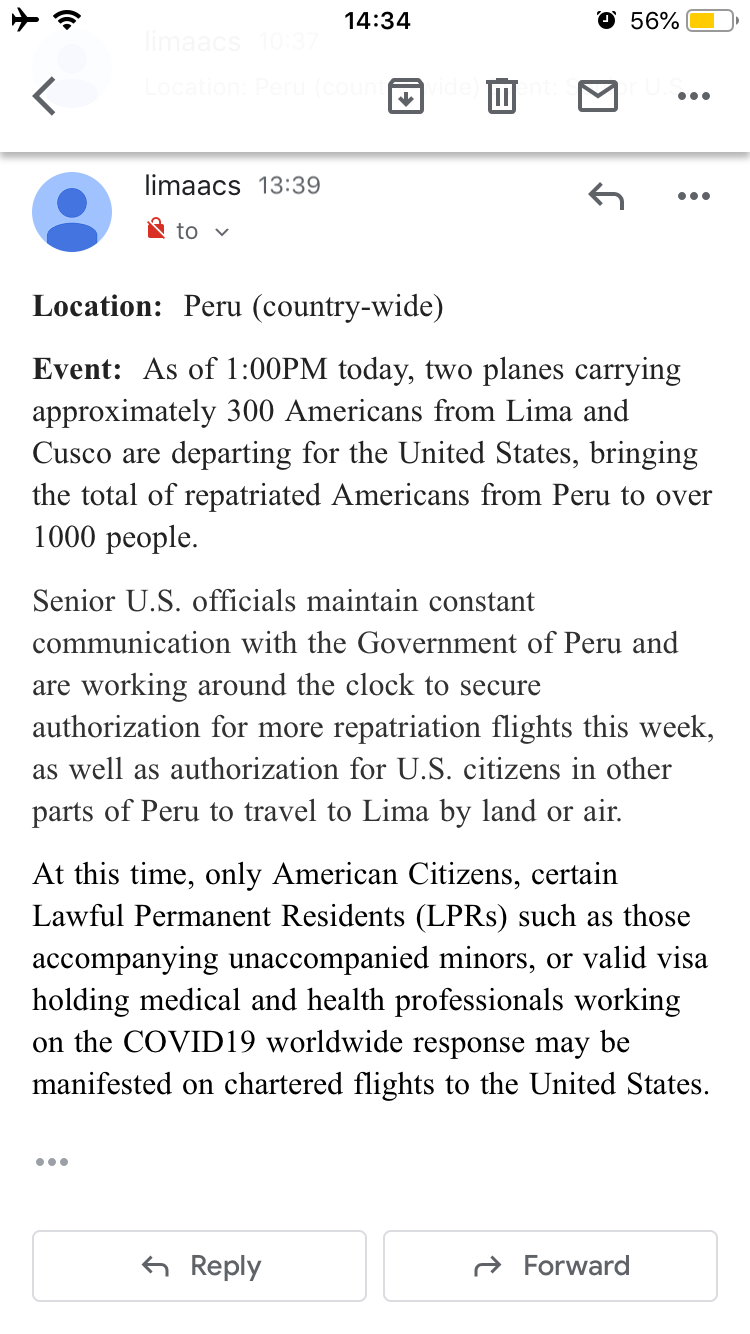

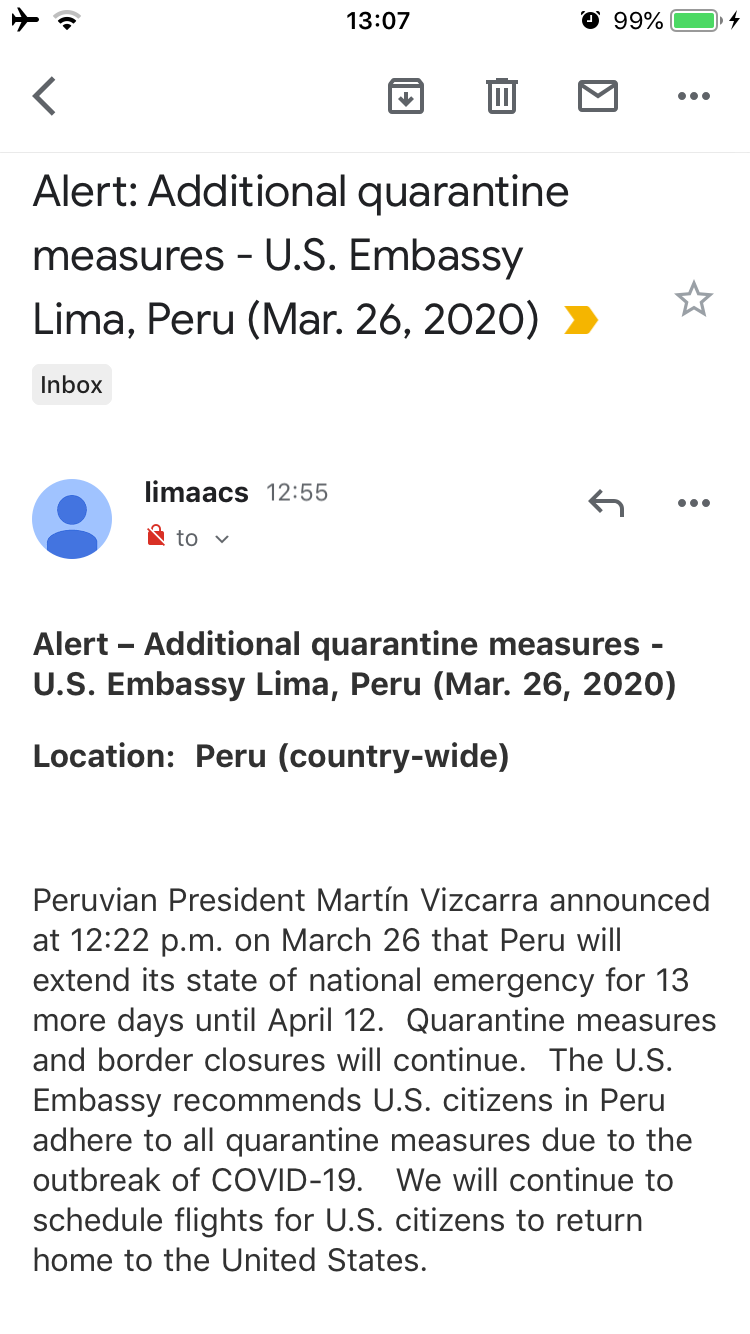

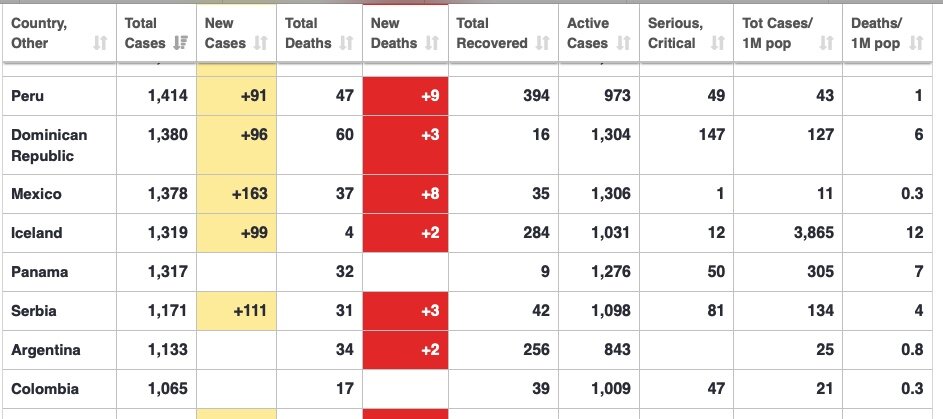

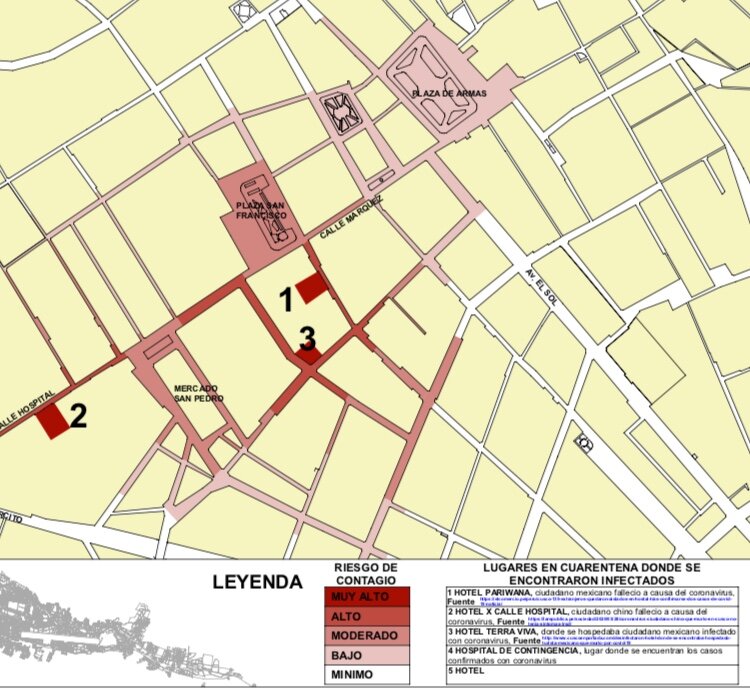

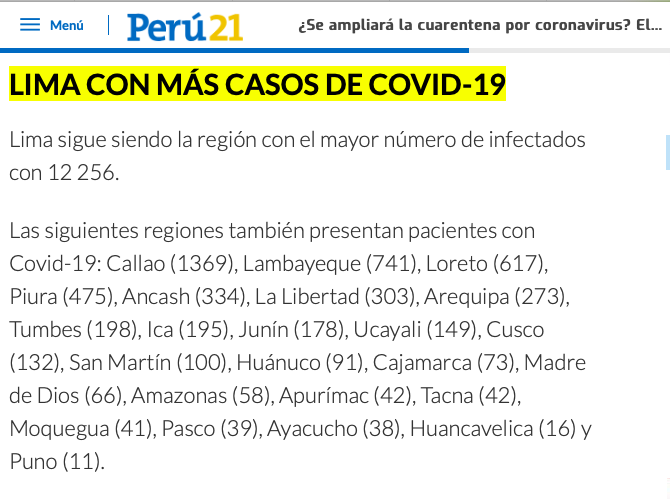

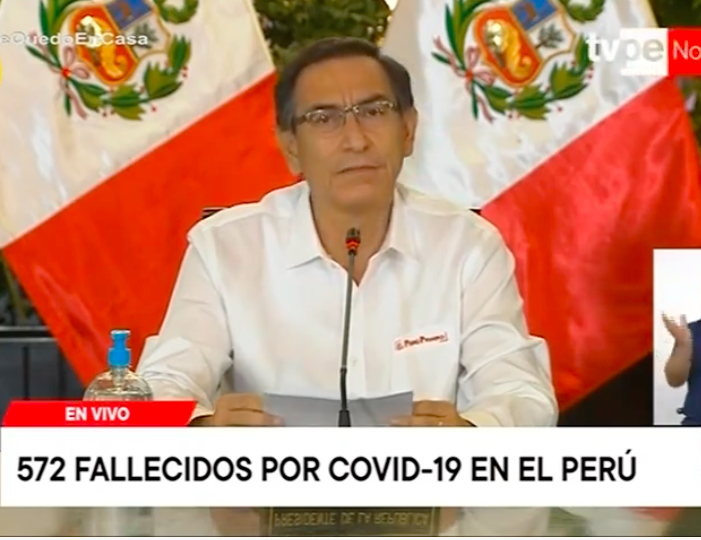

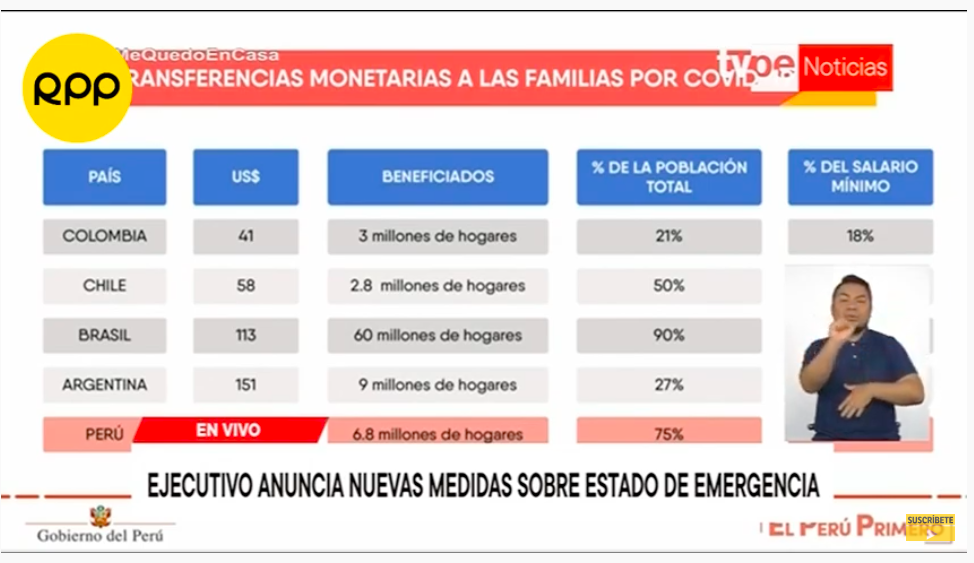

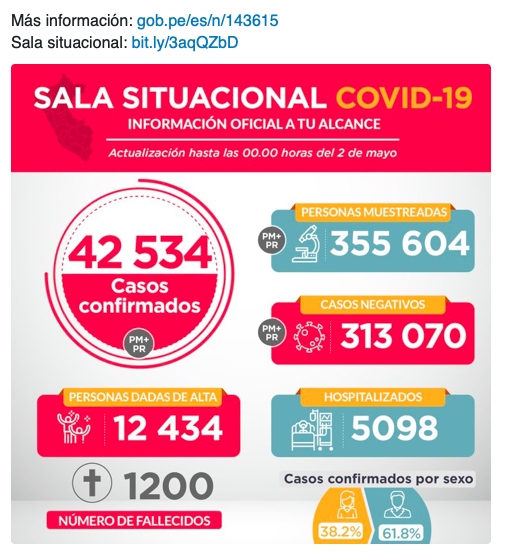

For a trip down memory lane, below are some of the emails I received from the US Embassy in Lima, and also official numbers and information from the Peruvian government. I watched the numbers of cases in Peru climb, as well as the number of American evacuated to the US. Throughout the evacuations, the pandemic situation in the US was much worse than in Cusco and I felt safer staying here. I still think it was safer to just stay put than to travel, even on a repatriation flight. It’s amazing how shocked I was when we had more than a handful of deaths in Cusco. I was so sure that we would escape the pandemic in the beginning. I thought that Cusco would stay isolated until it was over. I put a lot of stock in a National Institutes of Health study about altitude having a significant effect on the virus in terms of both transmissibility and severity. Since then, another study has shown that it’s less easily spread, but just as deadly.

Covid in Cusco: Week 41

The Covid Relief Project goes to Hatun Q’ero and I take the calculated risk of two Christmas parties.

Sunday, 20 December, 2020

Hatun Q’ero is about a six hour drive from Cusco, which is why we asked the mayor of Paucartambo to send transportation that could pick us up at 5am. The night before he had sent a large truck to pick up twenty desks which were generously donated by the school where Henry’s sister teaches. Of course, the school has been closed all year due to the pandemic, so nobody has gotten to use these desks in 2020.

All of the villages of the Q’ero Nation are part of the district of Paucartambo. Last Sunday, Sofia, who works in the Paucartambo’s mayor’s office, organized everything for our visit to Japu. Unfortunately, she was not available this weekend and we didn’t have anybody like her to help everything go according to plan. We were at the Maytaq Wasin, ready to load the food and clothes, at 5am. When Auqui called to check how close the trucks were, we were told that they were just leaving Paucartambo. That meant, the best case scenario would be that they would get to Cusco two hours late.

Henry, Auqui and I have gotten used to long hours on twisty mountain roads, and very long days, but I was a bit worried about our other volunteers. Kara and Katie were visiting from the US and had barely had 24 hours to acclimatize in Cusco. I wished that they had been able to get another two hours of sleep. Wilbert and his daughter Miska, Auqui’s brother and niece, were also joining us for the first time. We wanted them to enjoy the day, which was already going to be long, even without the extra two hours hanging out near the hotel. Henry’s niece Lucero was with us, but she’s already come to both Mayubamba and Marampaqui, so this wasn’t her first impression of how things go with the Covid Relief Project.

Eventually, two extended cab 4 wheel drive pickups arrived. We piled 160 bags of rice, two sacks of 300 oranges each and the two cans of 30 liters of fresh milk in the first pickup. The second pickup got 160 bags of salt, 320 bags of oatmeal and eight sacks of children’s clothes. It was almost 8:00 when we left, which meant that we didn’t get to Hatun Q’ero until almost 2pm. Nothing had been open in Cusco so early on a Sunday morning, so none of us had eaten breakfast. The community hadn’t prepared any boiled potatoes or anything else for us, plus there wasn’t really any time for lunch anyway. I am so thankful for all of our volunteers, who stayed helpful and cheerful during a very, very long day!

We started with the distribution of children’s clothes while the hot chocolate was being made, like we have done with the previous four chocolatadas. As always, many people did not have a cup, but thankfully somebody had a key for the school and they brought out the cups that children used to use during lunchtime. We served the children first, then Lucero went around to collect the cups from the children to be used again by the adults. Somebody in the community brought us a bucket of water with some bleach in it, to rinse out the cups.

There are no cases of Covid in the area, so the worst they could catch from each other would be the sort of cold that people passed around before the pandemic. Coming from Cusco, we are always very aware that we are the greatest danger they have faced since the pandemic began. We keep our masks on and I make sure that anybody handing out panettone is wearing gloves. Considering that we are outside, as long as we keep our masks on, the risk of one of us spreading Covid to them is very low, even if we are infected and asymptomatic.

After everybody had hot chocolate and panettone, the community president called out names from a list of heads of household while we distributed 4 kilos of rice, 2 kilos of sugar, 1 kilo of salt, 2 bags of oatmeal, 2 oranges and an extra panettone to each person. In theory, one adult representative from each family is supposed to receive the donations. In practice, many elderly people who live alone are not able to walk to the village and somebody has to stay out in the mountains, watching the alpaca. Often, children watch alpaca, but since we were giving out children’s clothes, and since hot chocolate is so popular with children, many parents sent the kids to the village and stayed to watch their alpaca. Several men came through the line four or five times and we teased them about how many families they had, although we knew that they were going to be taking the food to families that were unable to send an adult to the village. Also, there were many elderly people who had come to the chocolatada, but who were unable to walk through the line carrying about 8 kilos of food. Young men came through the line, then took the food over to their elders. I assume that they also helped them carry the food home at the end of the day.

We are used to sitting around after we distribute the donations, sharing food or just chatting with the villagers. Unfortunately, it was already past 4:30 and we really had to hit the road. It’s about two hours on very rough dirt roads from Hatun Q’ero to Paucartambo. From Paucartambo to Cusco the road is paved, but it gets dark not long after 6:00 and those mountain roads are much more dangerous after dark. The dirt roads from Hatun Q’ero to Paucartambo do not have any guardrails when there is a big drop off, or where the road is particularly narrow. The drivers honk when we drive around a sharp corner, in case somebody is coming in the opposite direction that we can’t see, but that only warns people. More than once there were alpaca in the road, which are as unaware as a cow would be of what a car honking around the corner would mean. Thankfully, alpaca are quite skittish and afraid of anything loud, so they generally flee at the sound of a car, truck or motorcycle. Few people can afford a truck out in the mountains and cars really can’t handle those roads, but there are always a couple families who have a motorcycle for going to town. It’s very dangerous to drive a motorcycle on those roads after dark, but sometimes you just can’t get home in the daylight, no matter how hard you try.

It was after 10:00 when we got home, tired and hungry, but happy to have been able to help the families of Hatun Q’ero, despite the logistical difficulties. I do hope to be able to go back some day, perhaps spending the night in Paucartambo so there is less of a drive to the village. I would love to hear from the Q’ero how the pandemic is affecting them and how they are experiencing the effects of climate change.

Monday, 21 December, 2020

Solstice is normally an important holiday for me, for my parents and for Peru. Growing up, my parents used to throw a Solstice Party and Mom would post sunrise and sunset times, so we could track the days getting longer. I loved December Solstice, because every day after that was longer, and therefore better. It was hopeful; it can only get better from here to summer.

Peru is too close to the equator for there to be a big difference between solstices, which is why last year I went to spend Solstice in Patagonia. The sun rose before 5am and set after 11pm. I got to see two species of penguins and lots of other wildlife. It was exactly what I was hoping for! Travel is still not really possible for me, so I am spending Solstice in Cusco this year.

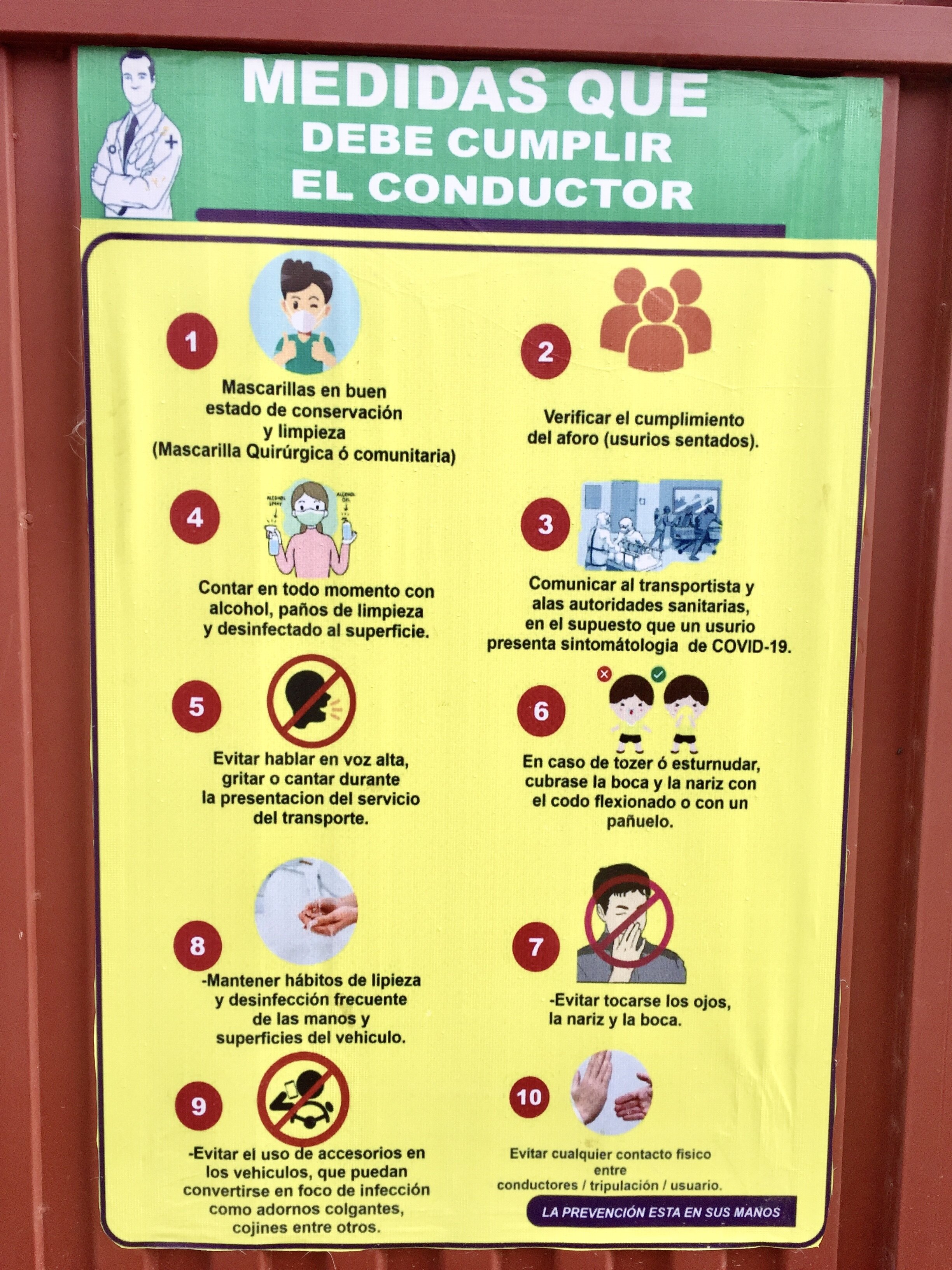

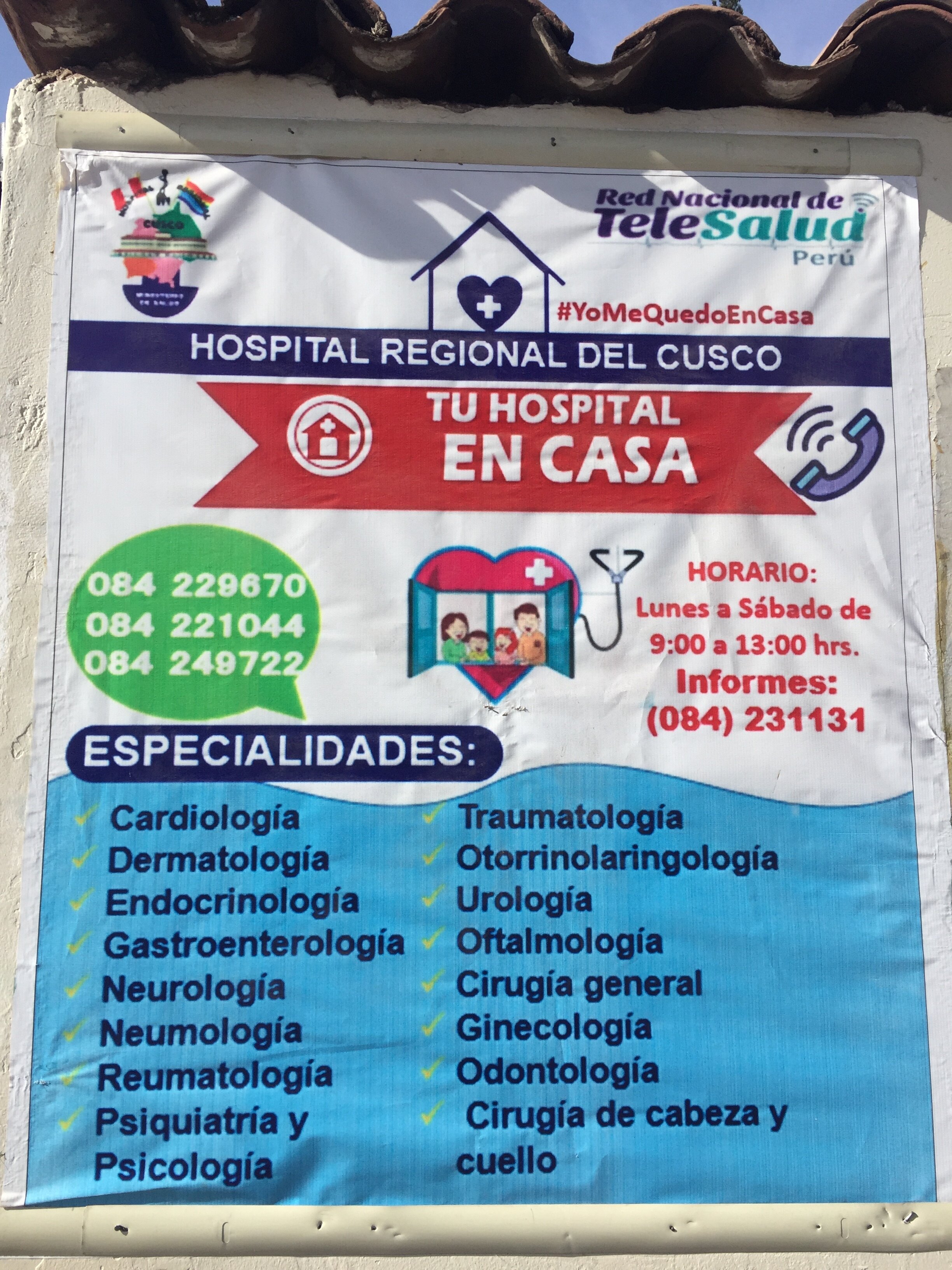

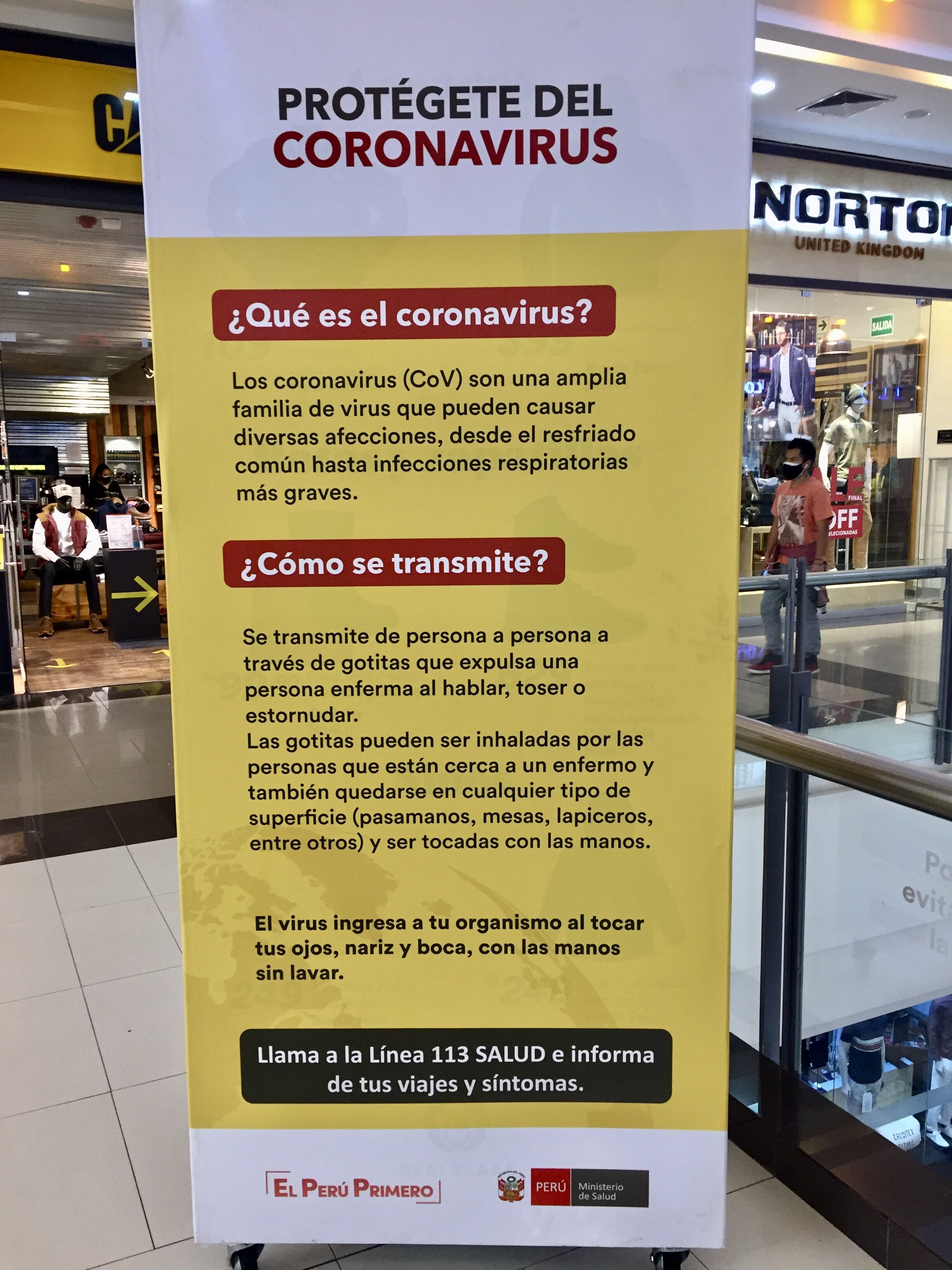

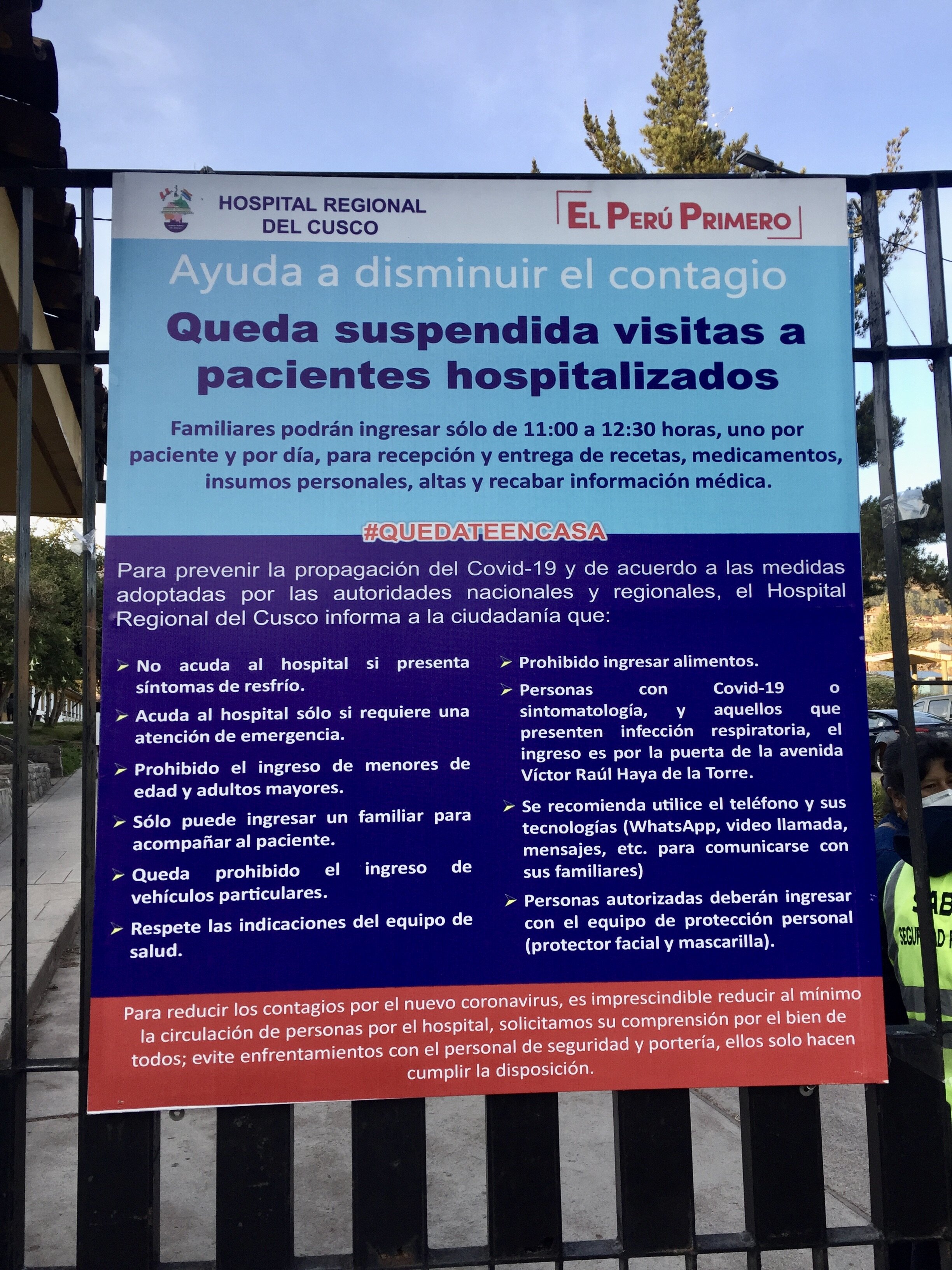

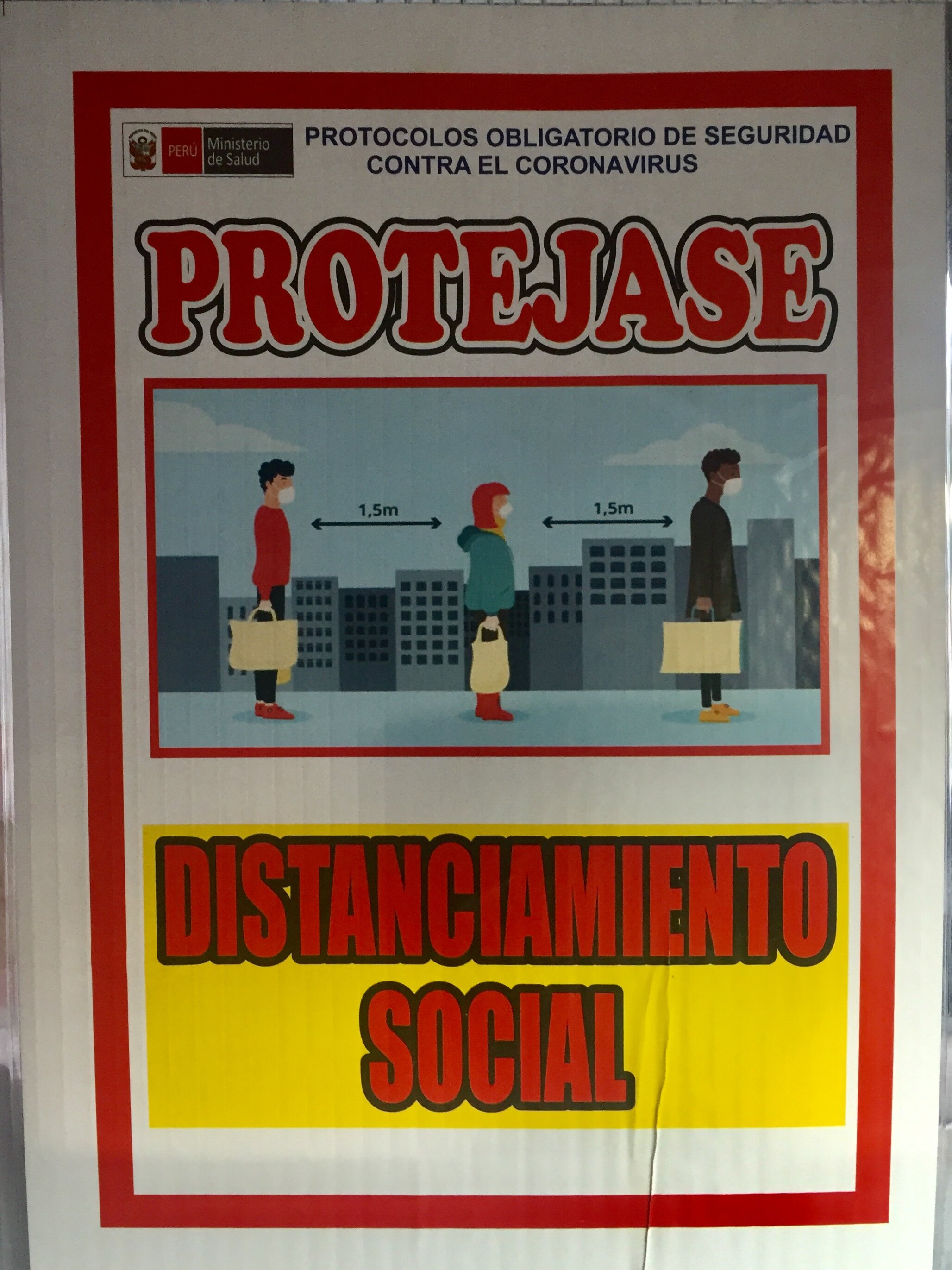

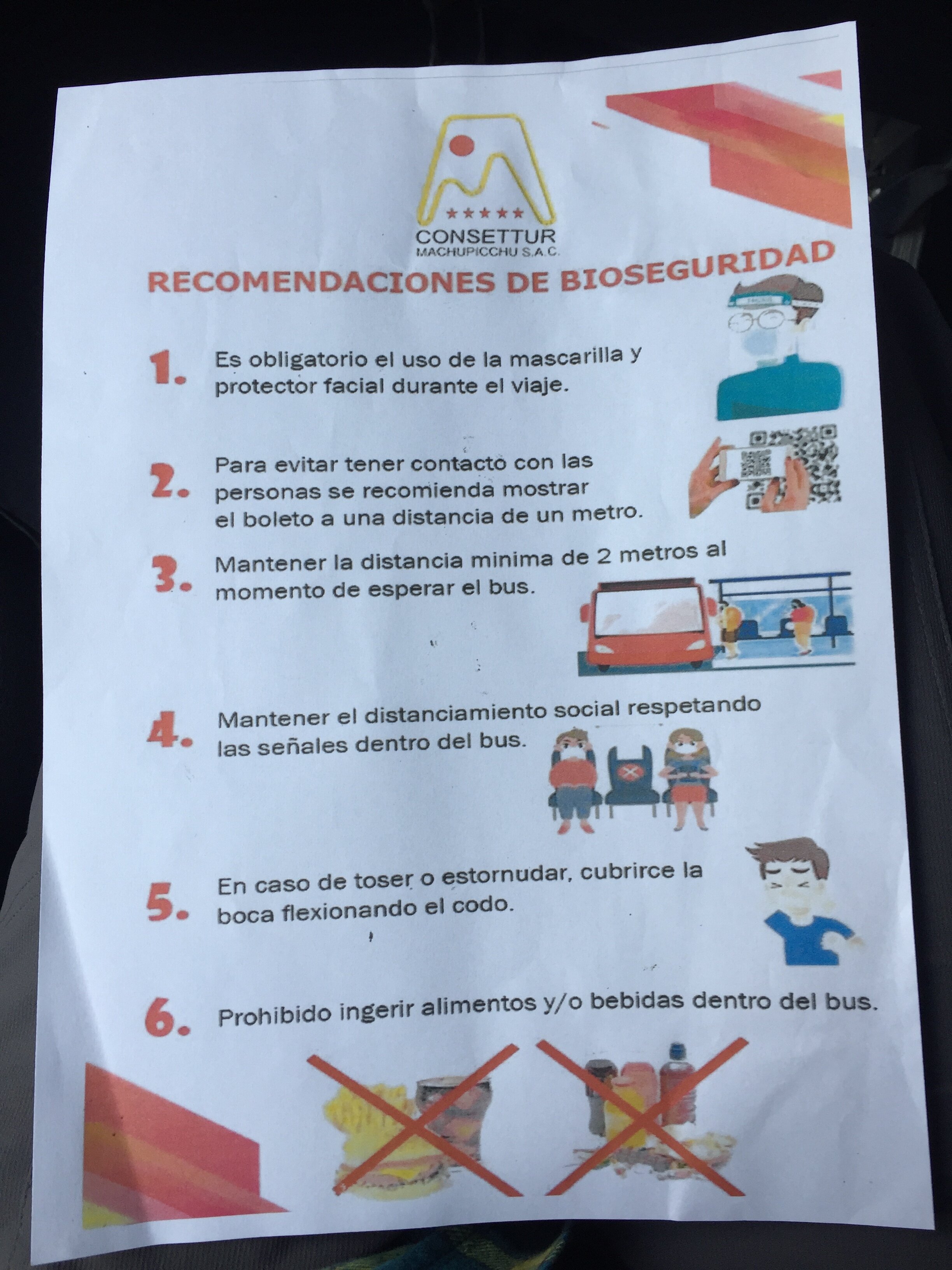

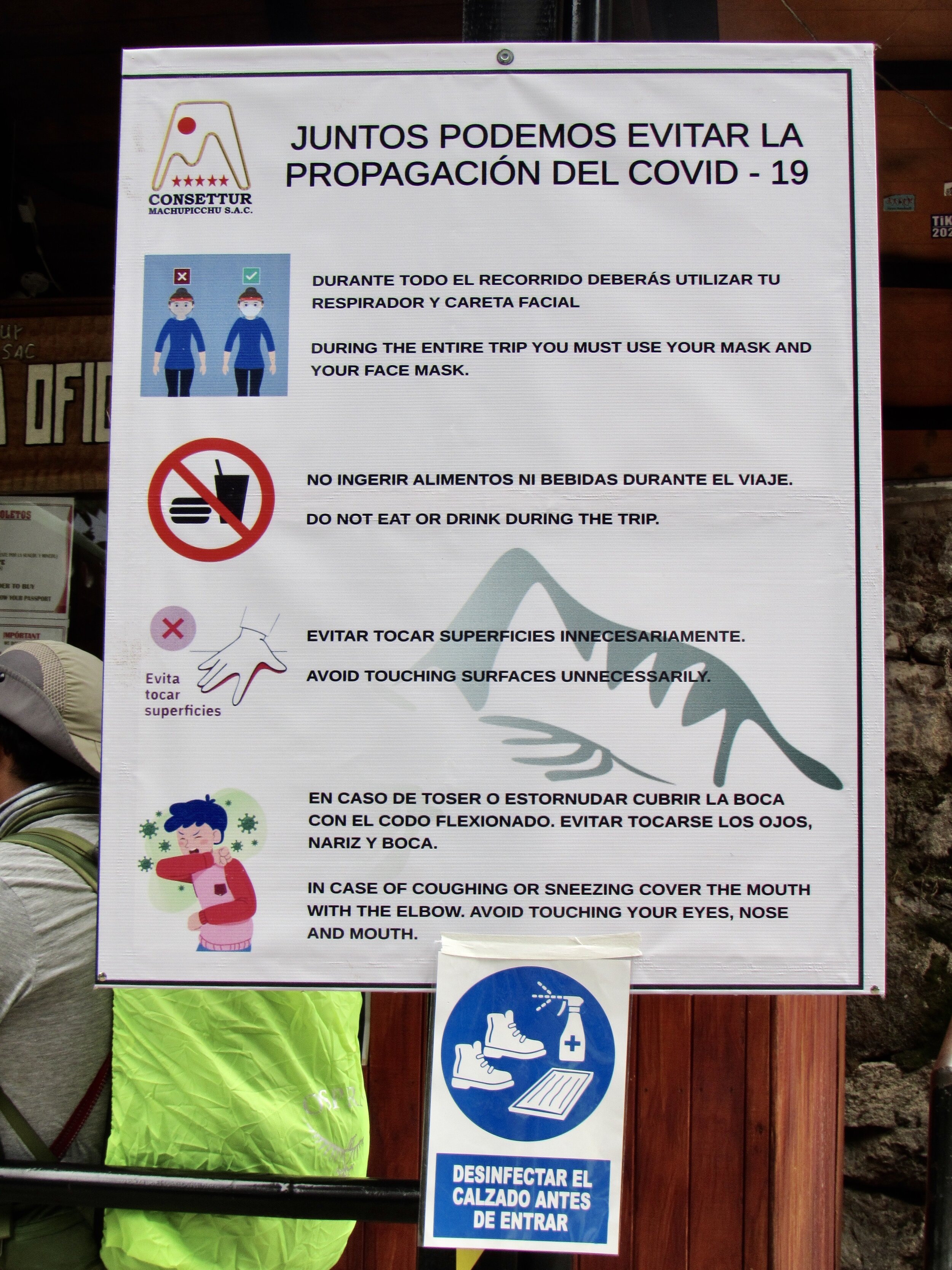

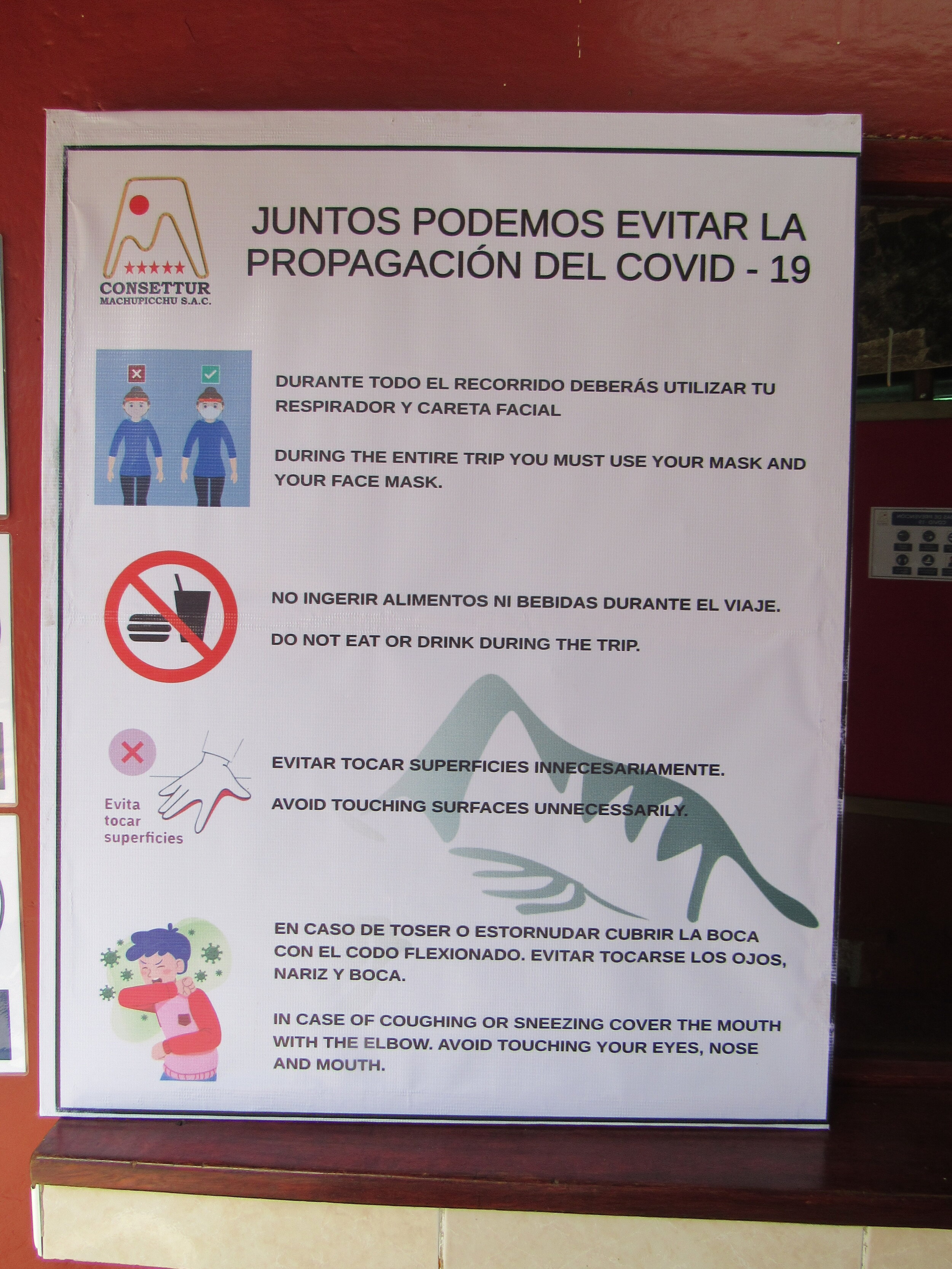

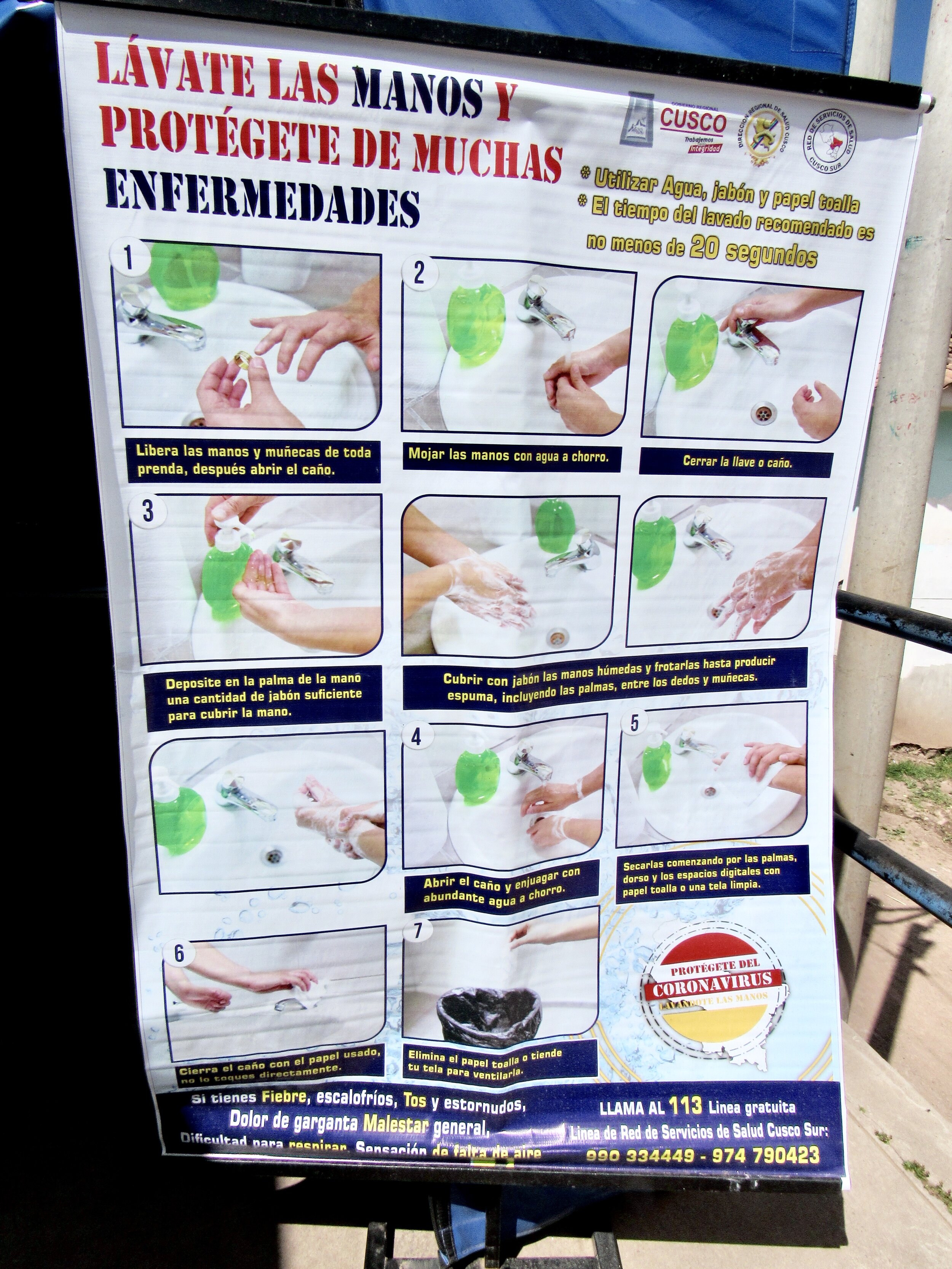

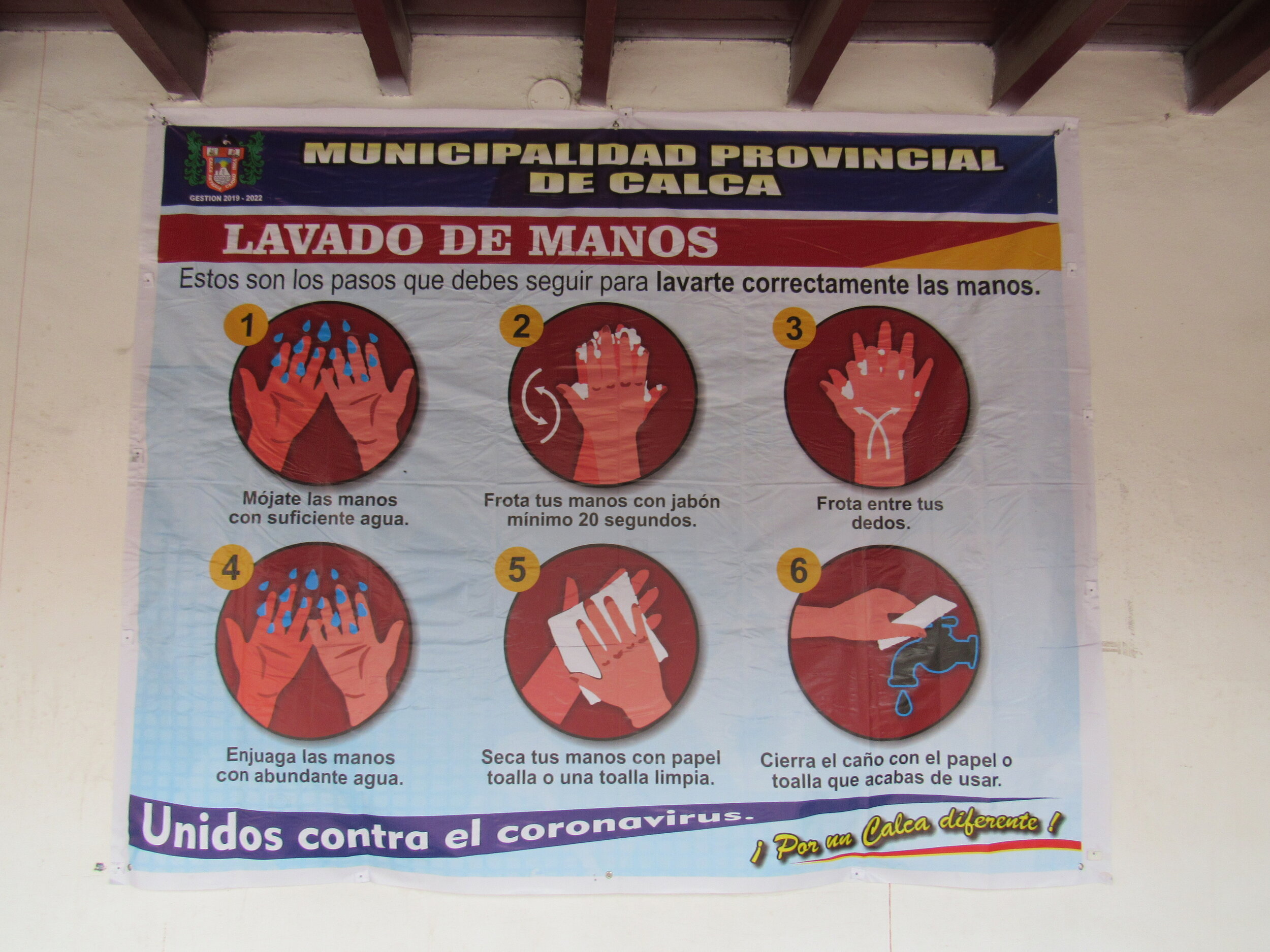

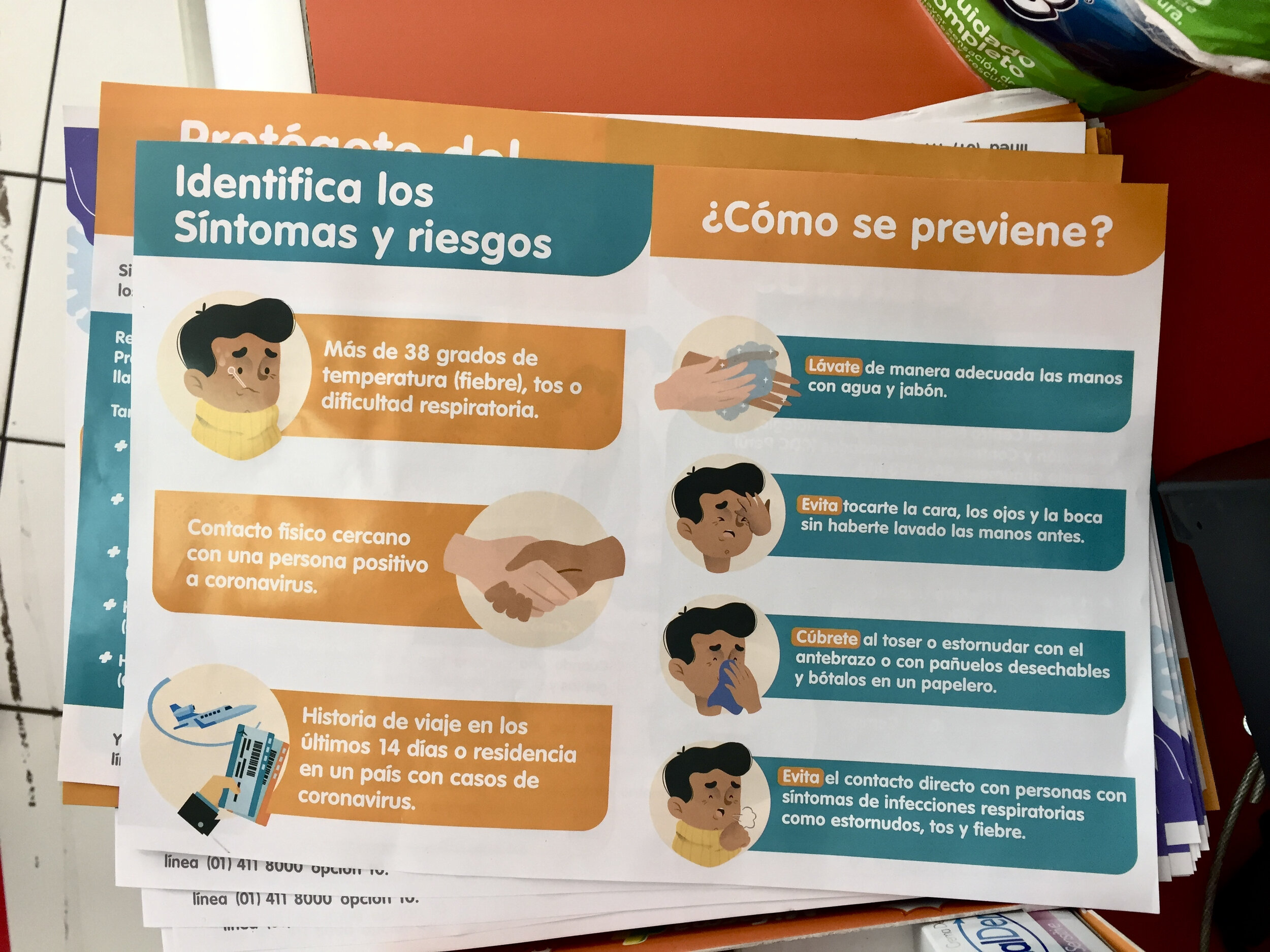

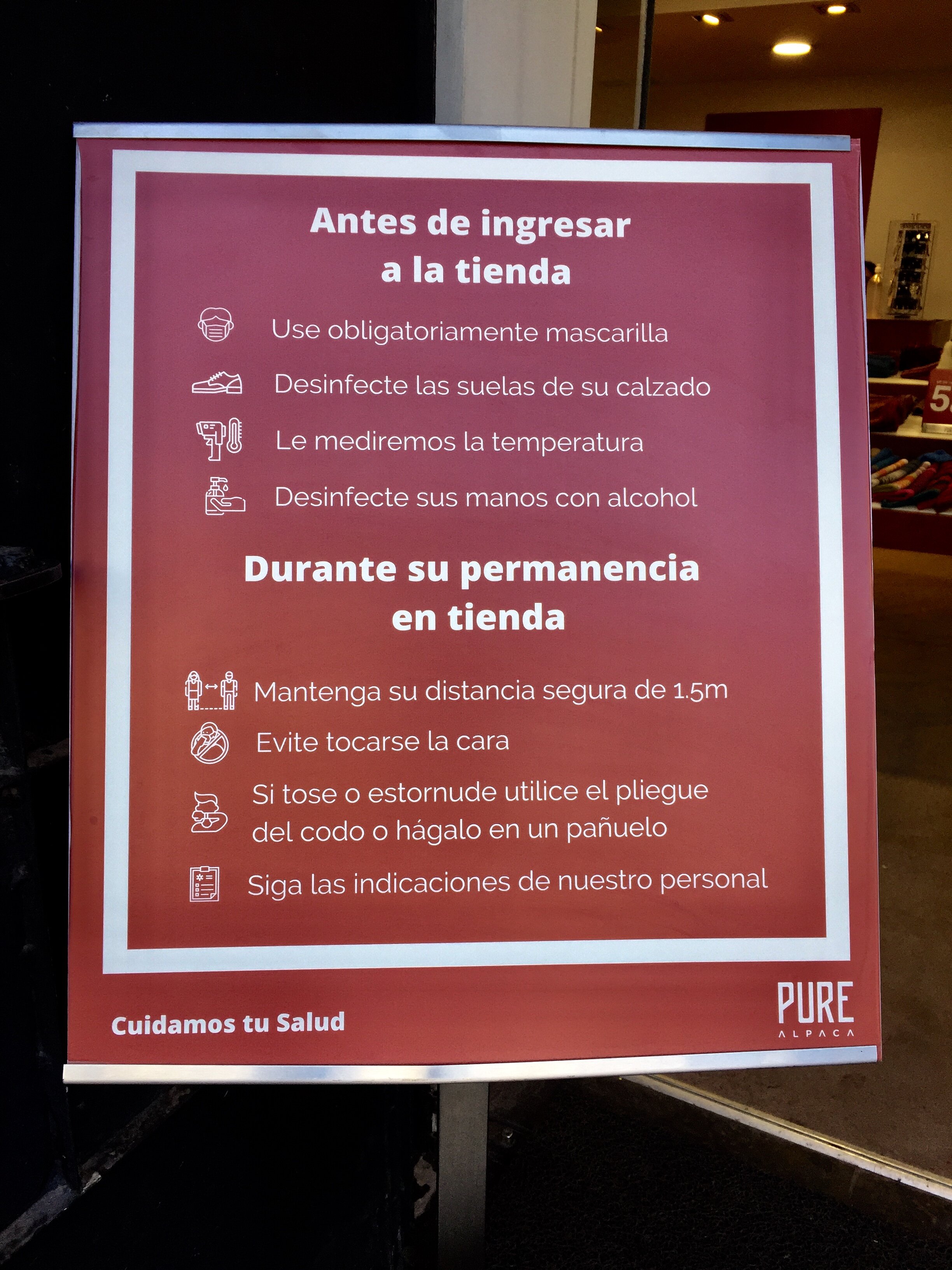

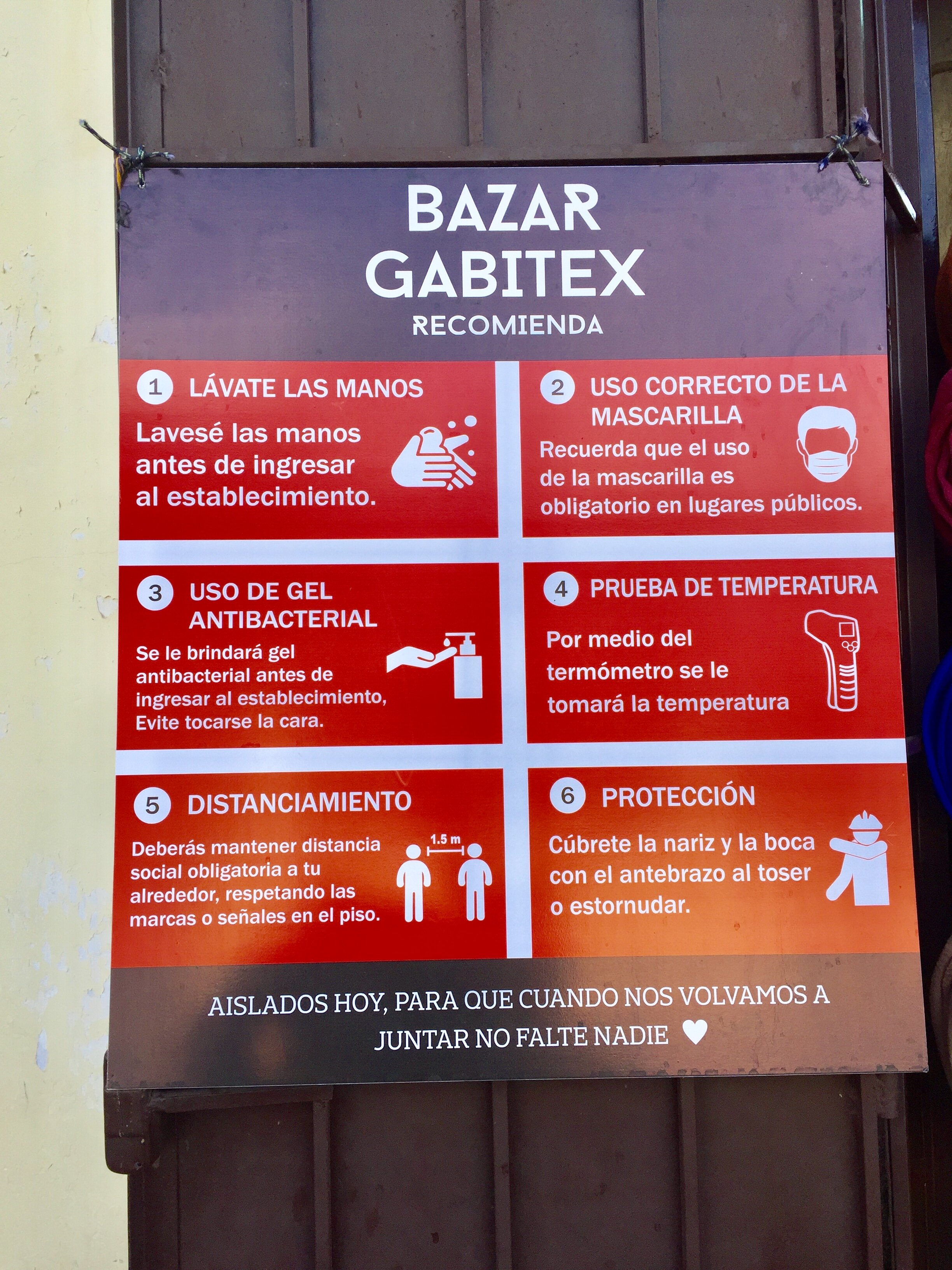

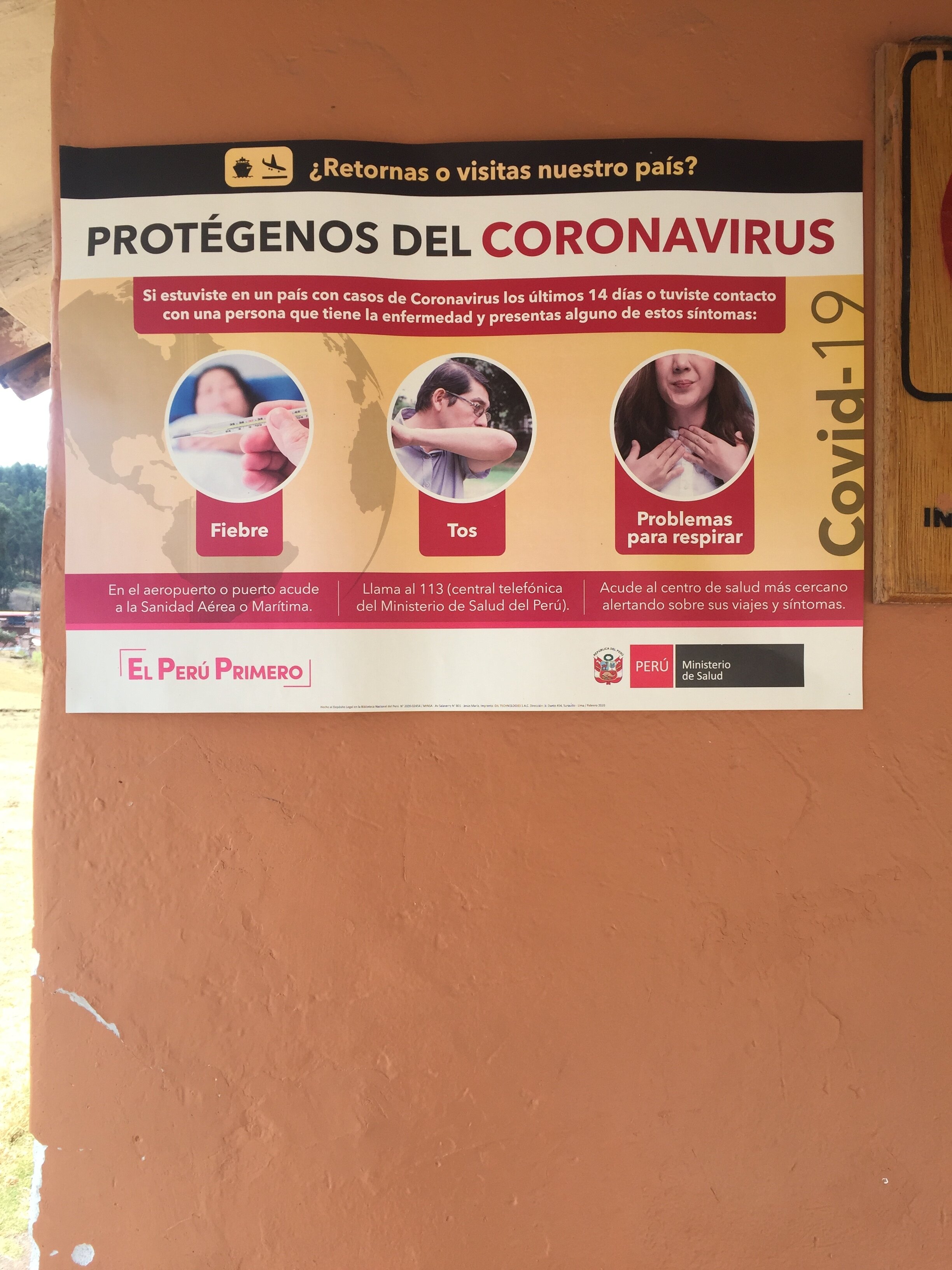

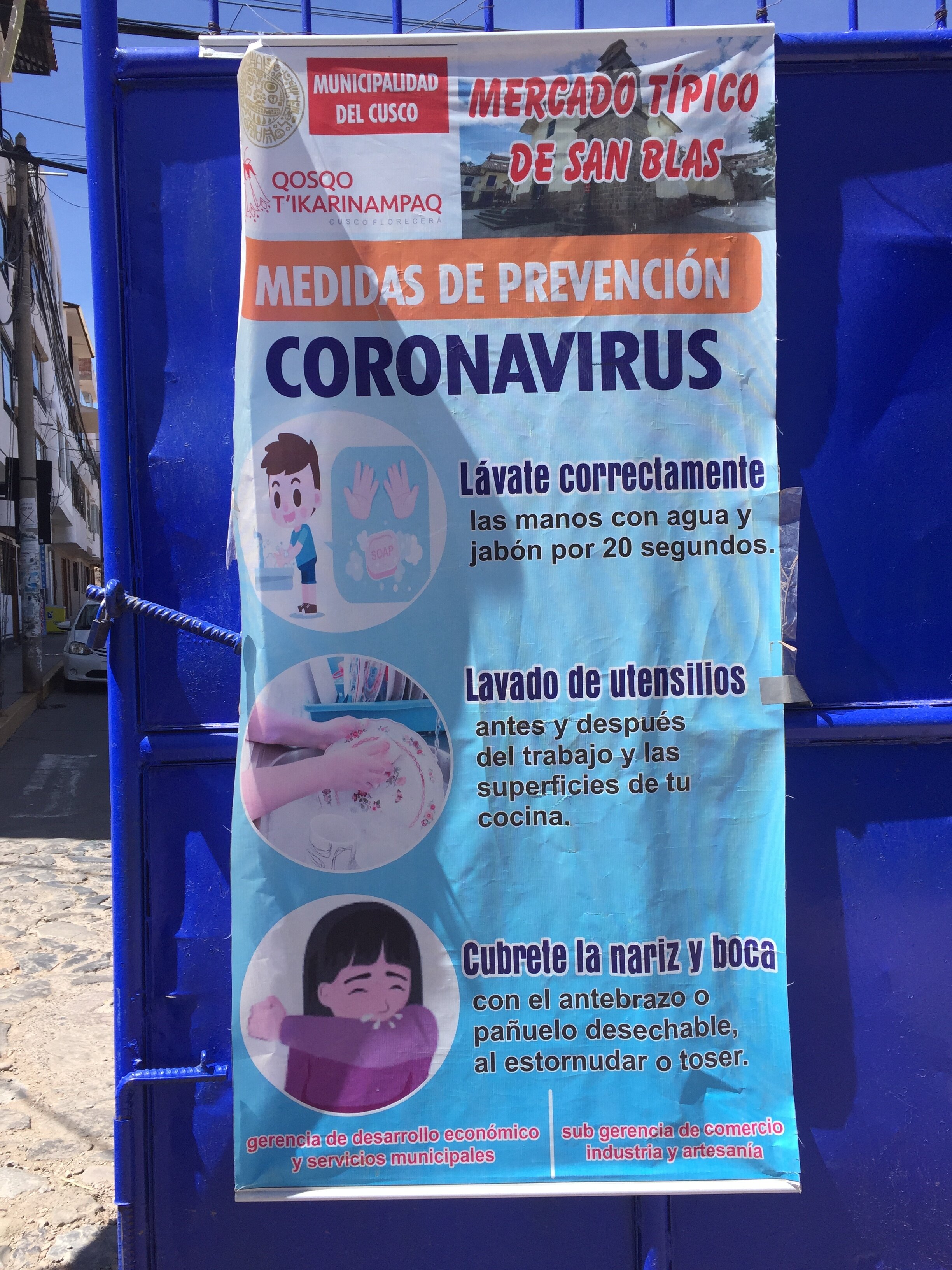

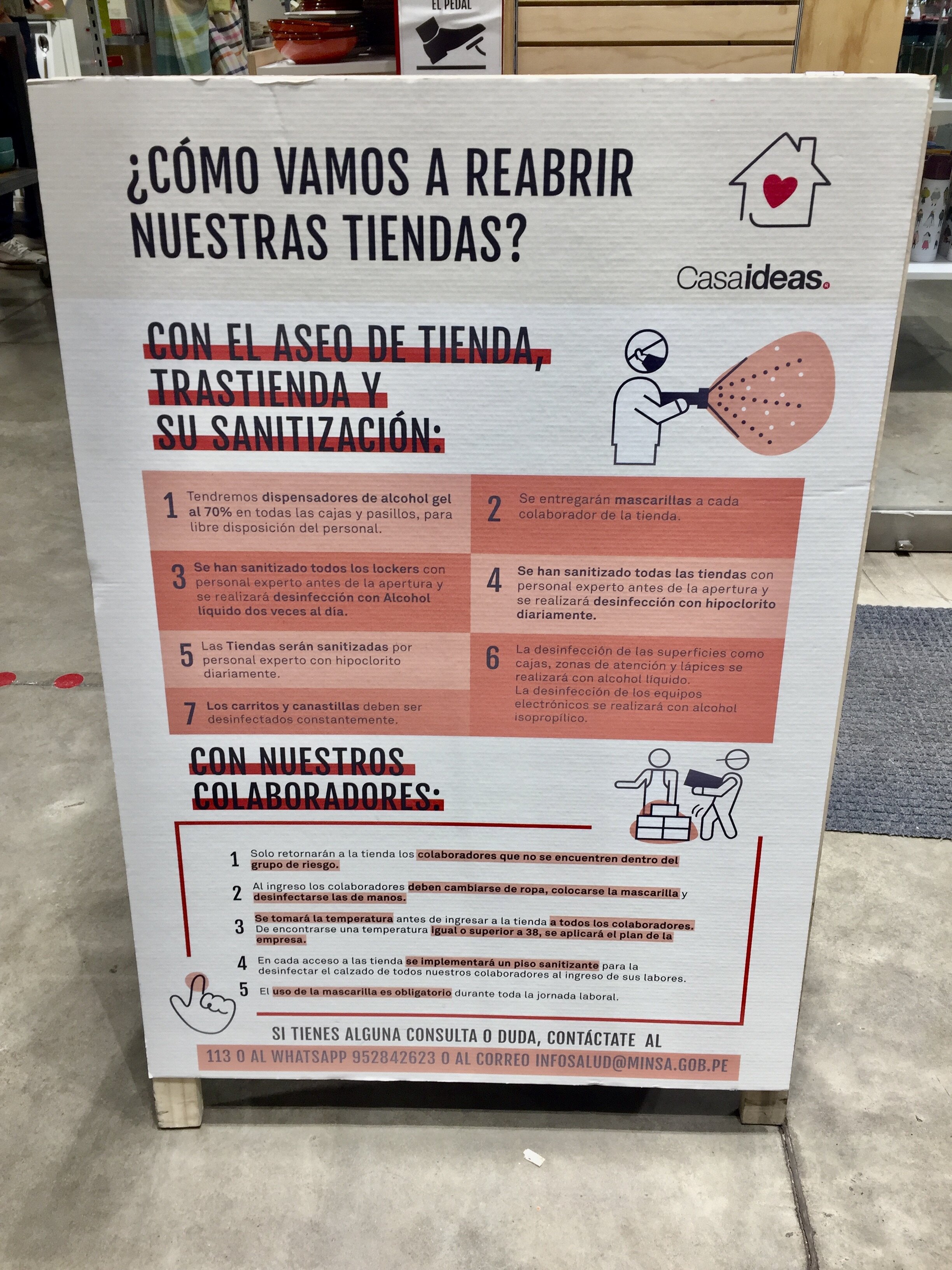

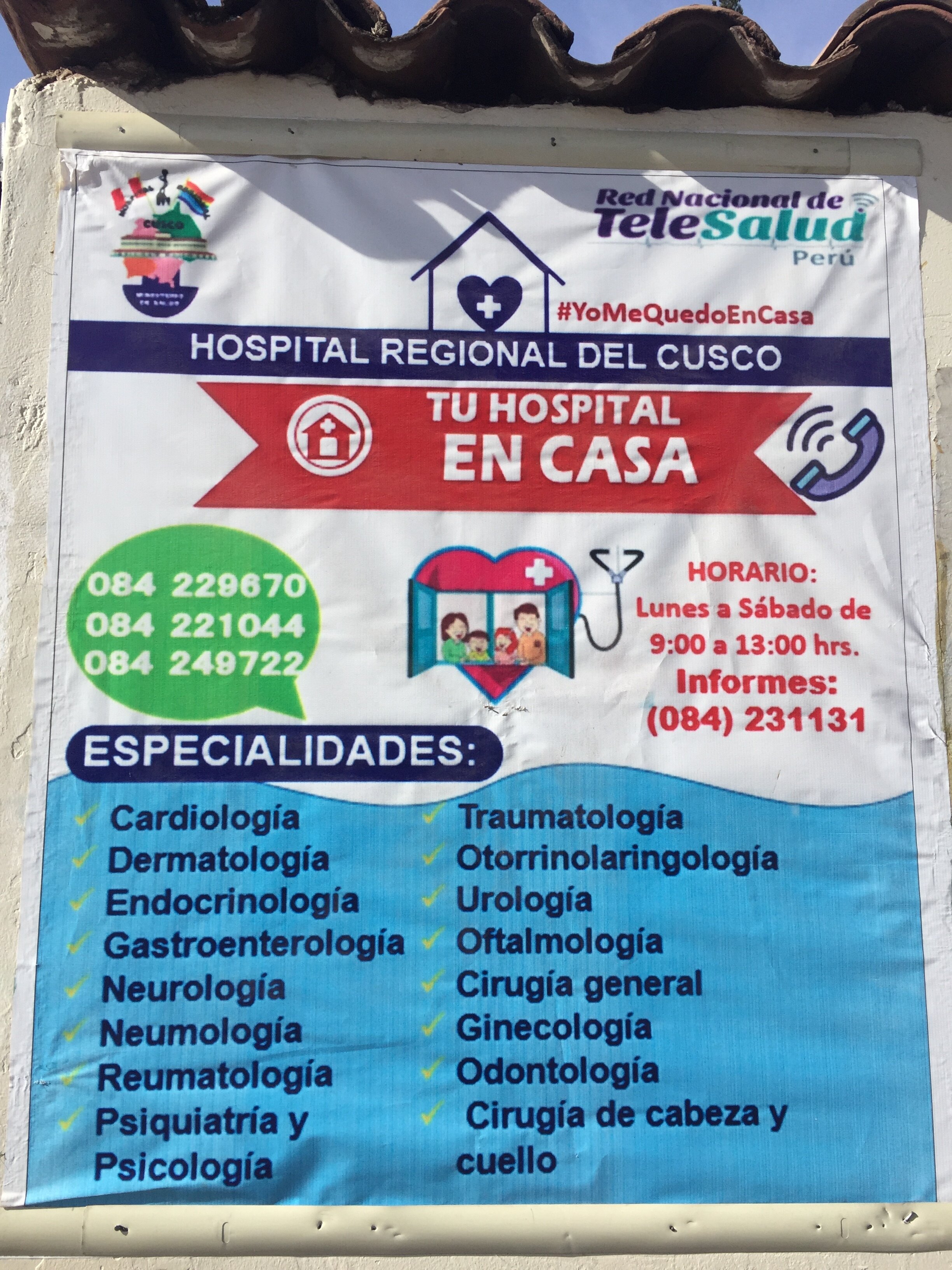

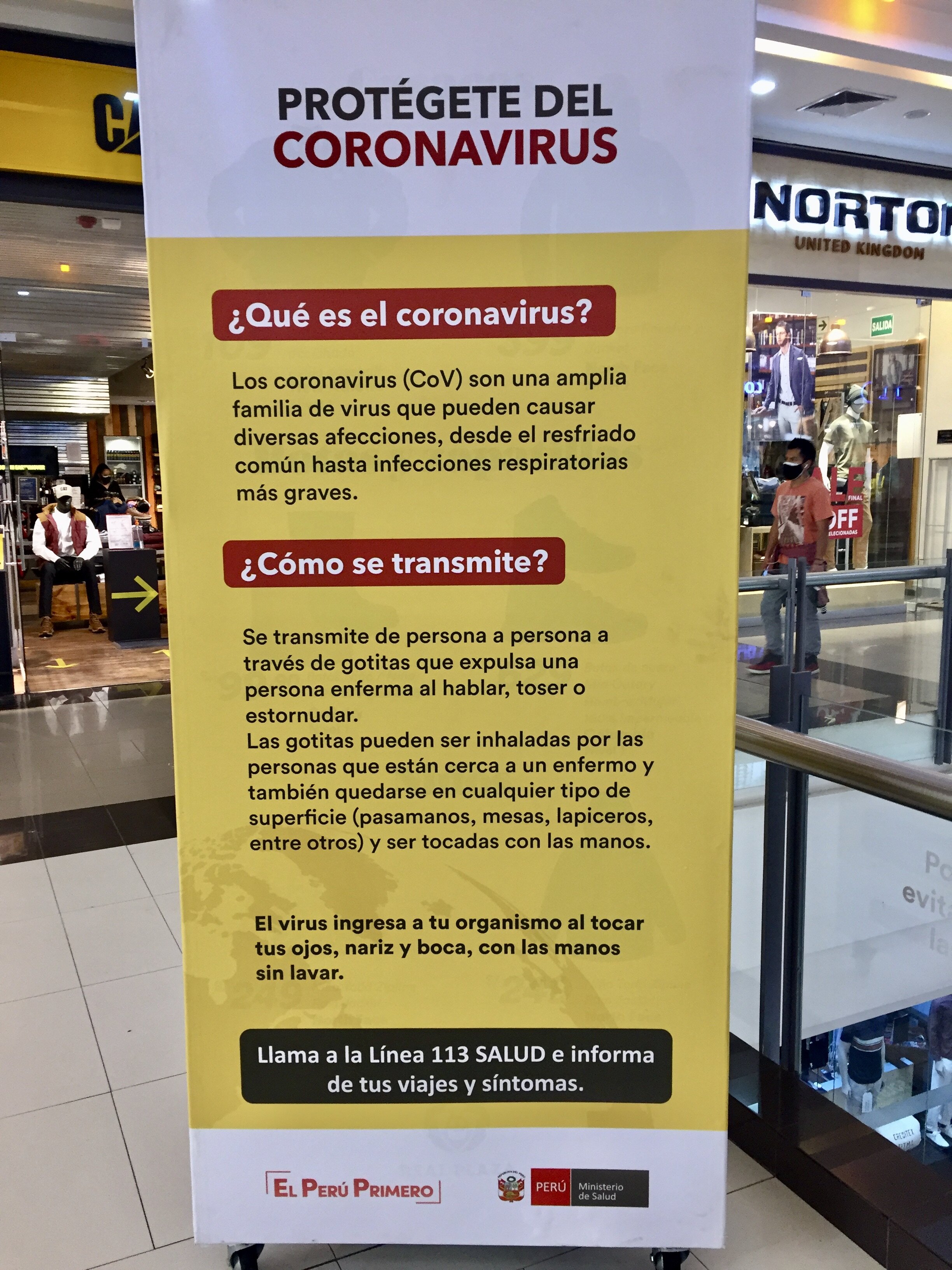

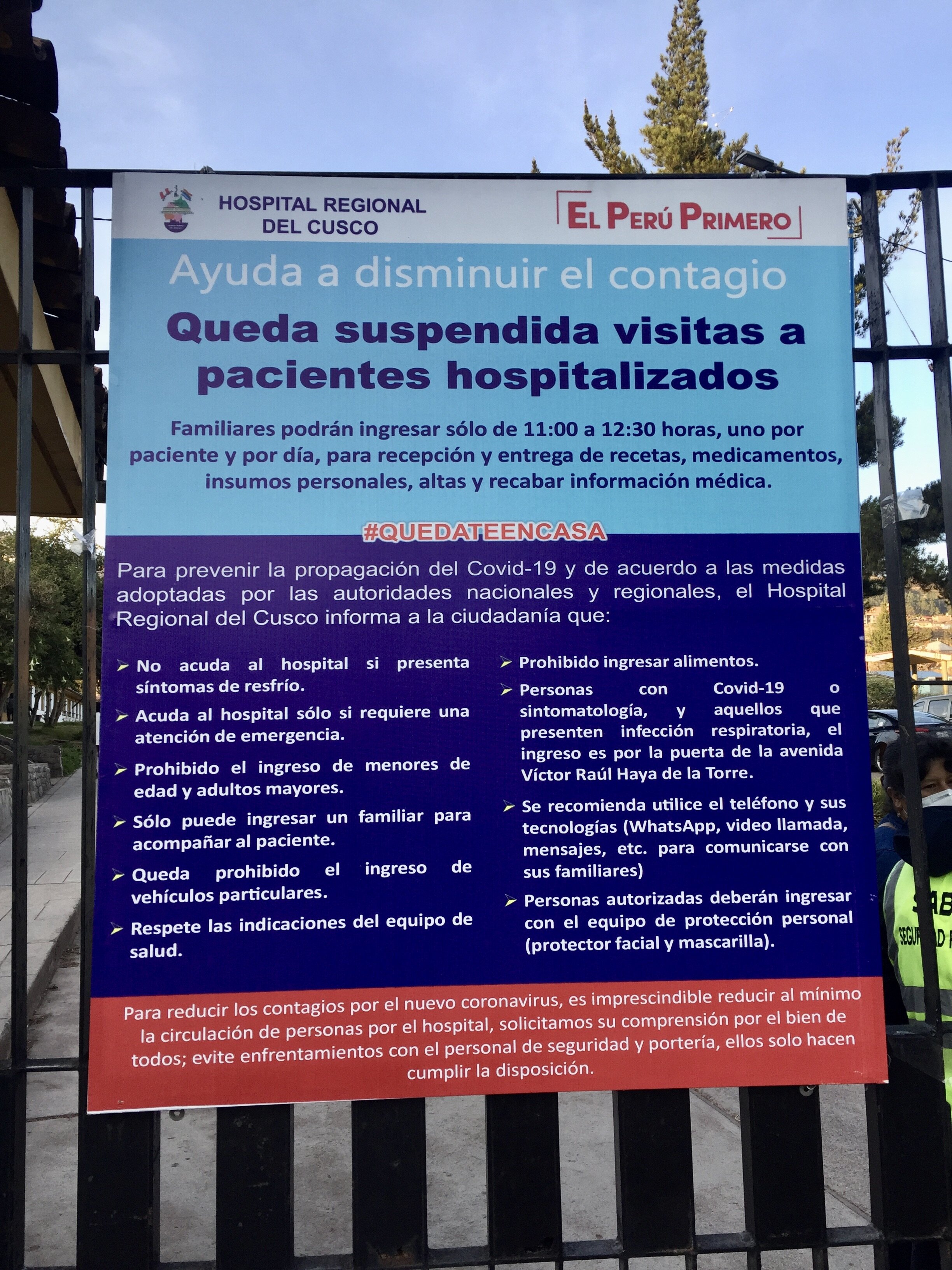

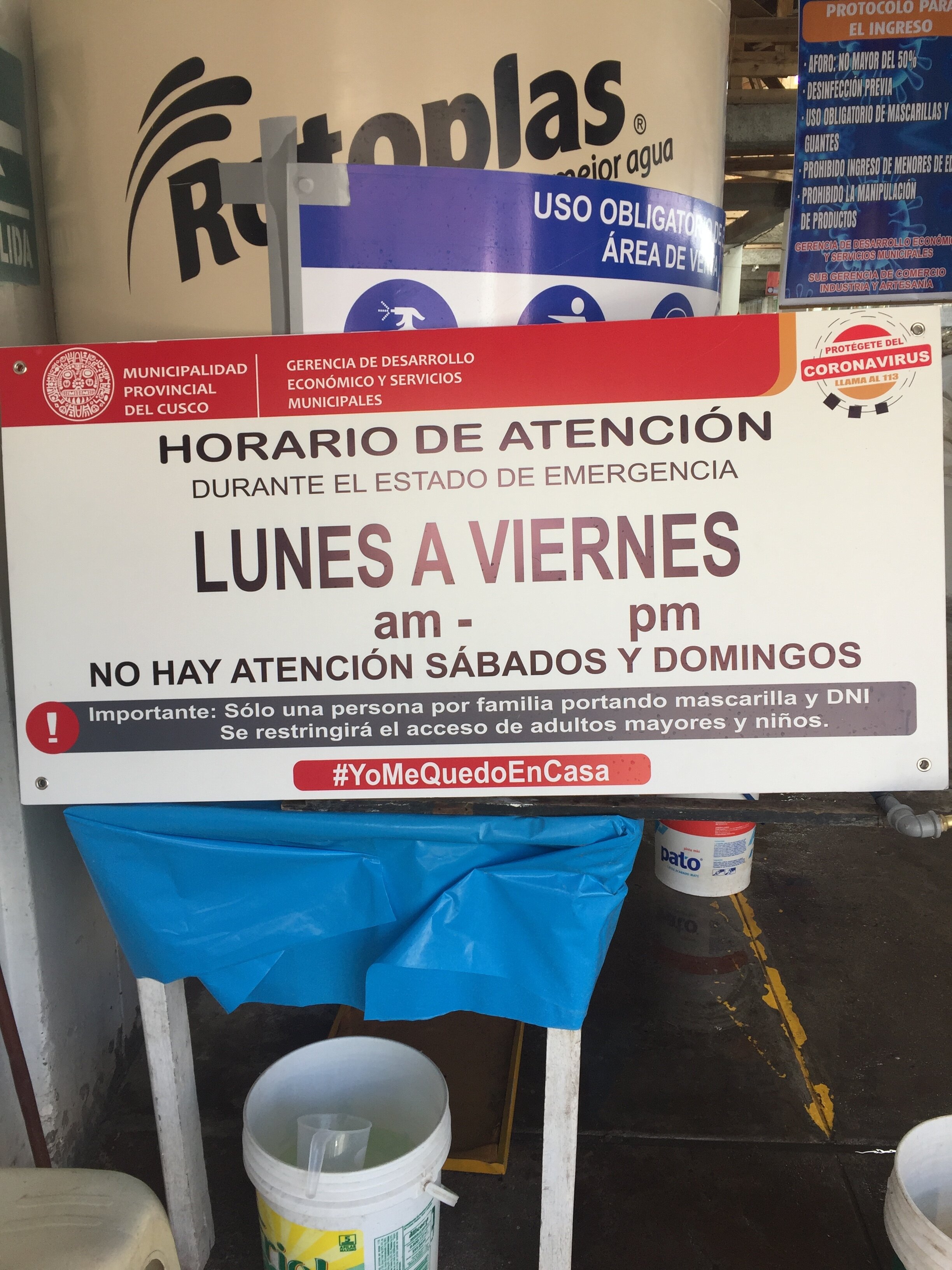

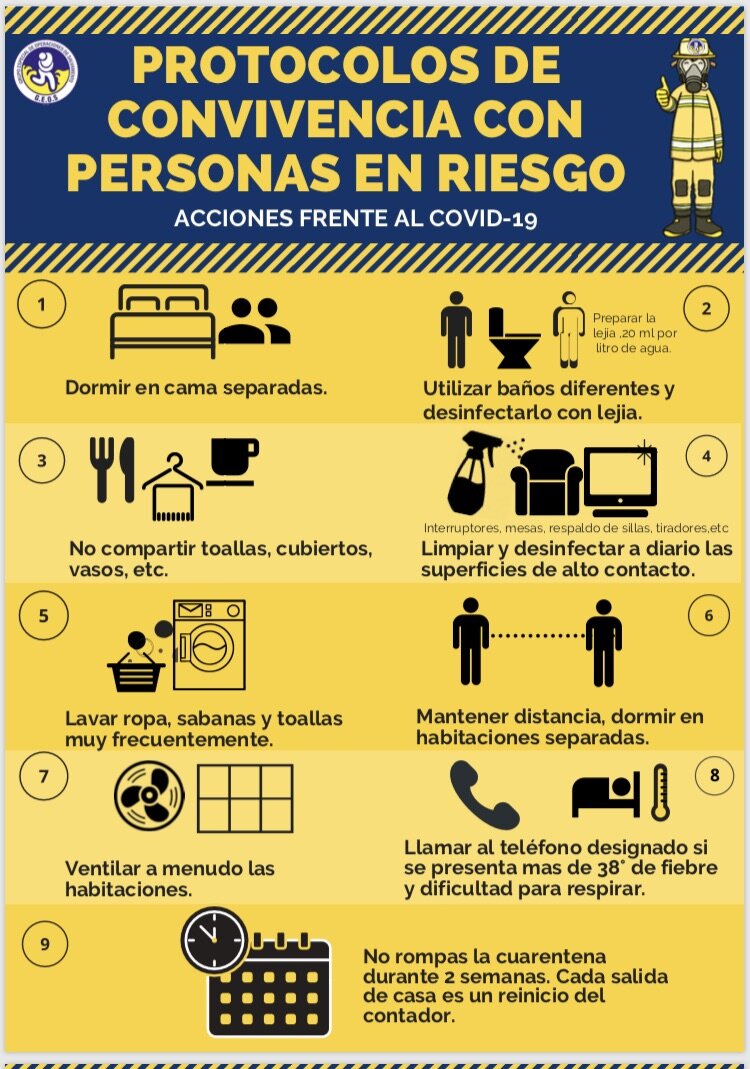

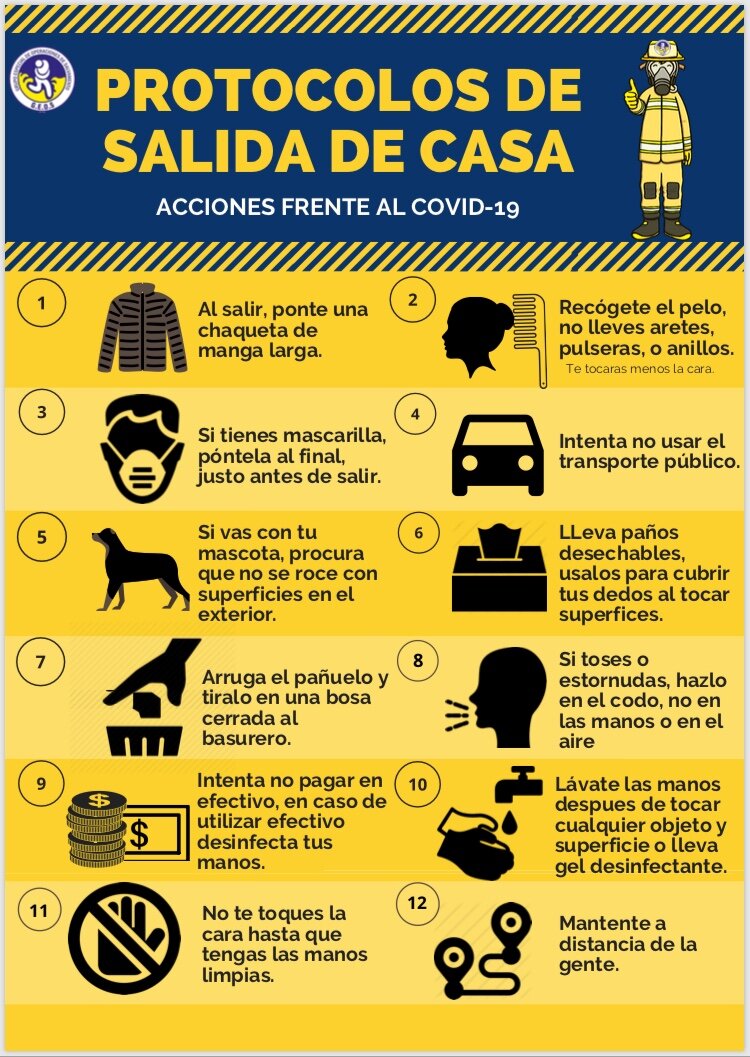

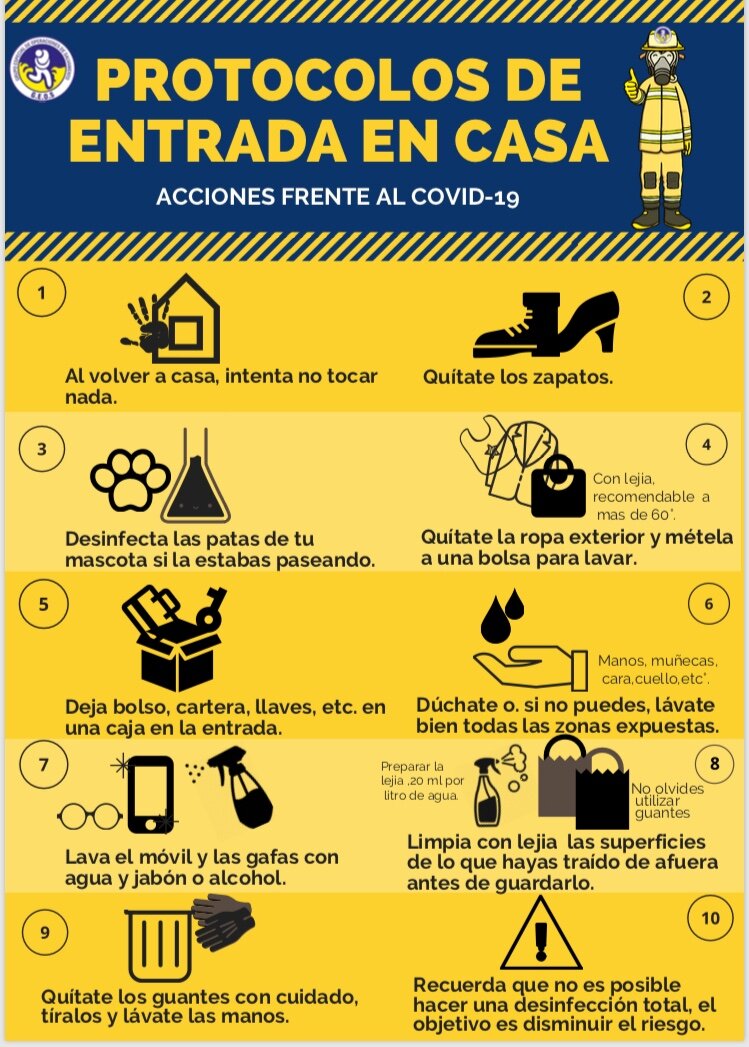

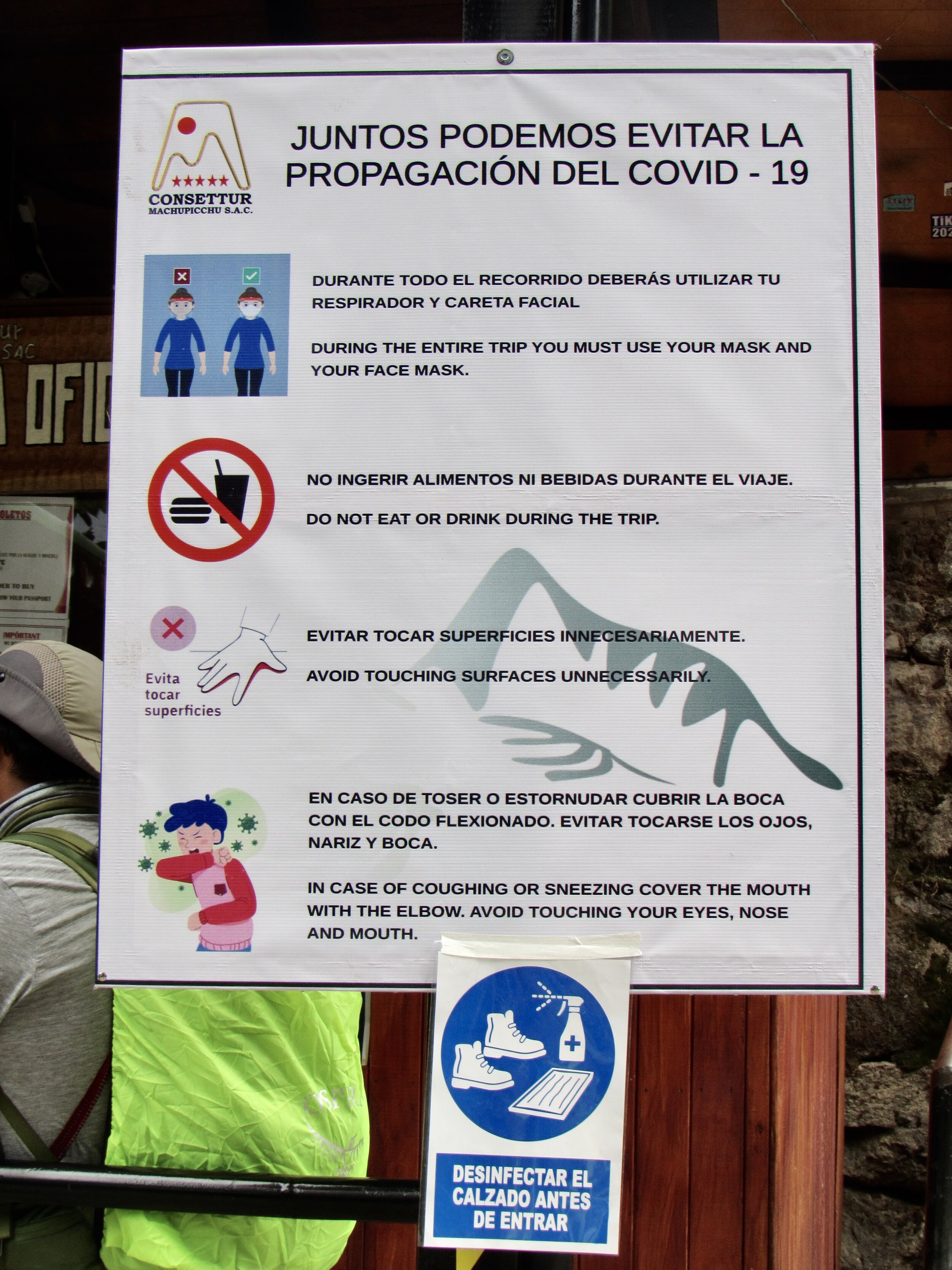

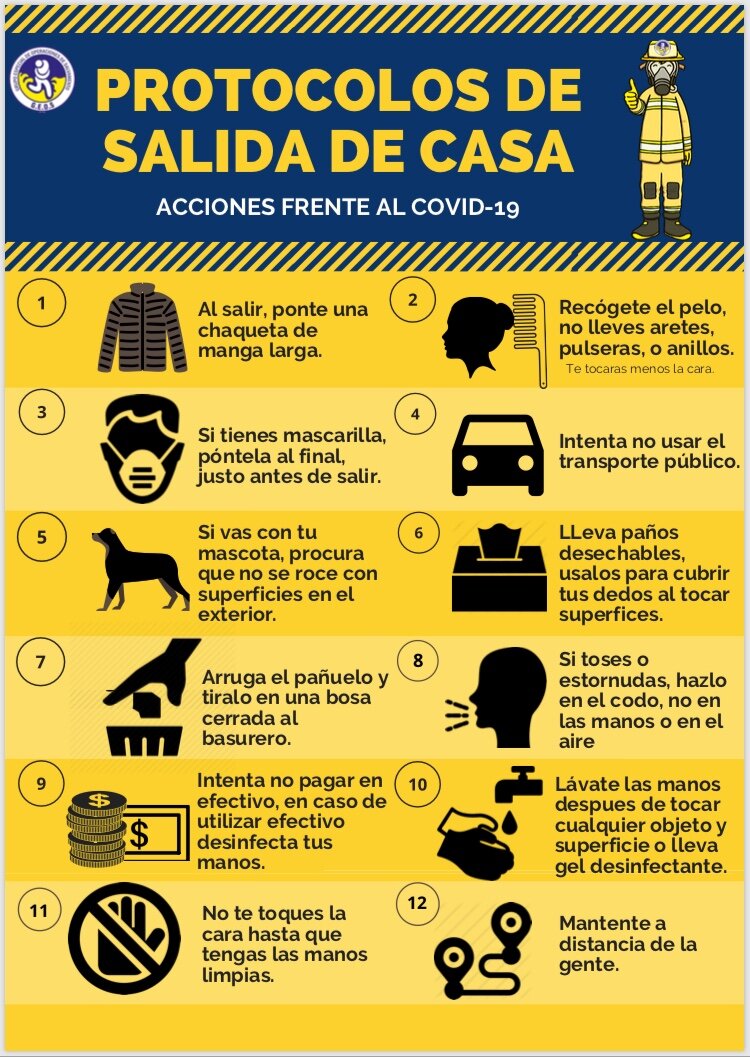

While I’m hearing reports of countries ending lockdowns or starting lockdowns, ending or starting quarantines, Peru has mostly stayed the same. We still have a curfew. Masks are still required outside the home. Masks and face shields are both required on public transportation. Cusco is covered with posters about how to prevent Covid. Every business and all public areas like plazas and parks have handwashing stations. All of that has been the same since June, when we were finally allowed to leave our homes for more than just going to buy food or go to a pharmacy.

Except for the days I leave Cusco with the Covid Relief Project, or my backpacking trip around Mt. Ausangate, I still feel like I’m in an airport waiting room. It’s like the Bill Murray film Groundhog Day; nothing really changes. I can try to do different things, but it’s still the same day, every day.

Tuesday, 22 December, 2020

Today is day 282 of the state of emergency. Every once in a while I look at the Diresa website, to track the numbers in Cusco, but not as often as I was in September. We had a terrible outbreak in August and September, with over 2,000 new cases diagnosed every day. Thankfully, we have brought that number down significantly. Today, there were only 166 new cases and we’ve consistently had it below 200 for weeks now. In August and September we only had one ICU bed available, but now we have five available. There are only 23 ICU beds in the Cusco region, so we only have 18 people in ICU now.

Are those numbers low enough to have Christmas parties again? Probably not. Am I going to a Christmas party anyway? Well, yes. I’m going to risk it. Actually, I’m going to a big family Christmas Eve in Urubamba with Auqui, then to a Christmas day celebration with my expat family in Cusco. On the surface, that looks like a terrible idea. I am very aware that it only takes one person at either of those two events for all of us to get infected. I also realize that going from Urubamba to Cusco could take a Covid infection from one town to another.

I’m taking the risk because the numbers are currently very low and also because nobody in either of those circles has had Covid. I don’t know if that means I’ve gotten complacent or if I’m numb to the risk or if I just don’t care anymore.

Faced with the risk of travel in two months, a small part of me wants to just get Covid and get it over with so that when I’m traveling I won’t have to worry about getting infected. Even if post-infection antibodies decrease after four or five months, right now I’m worried about February, not June. If I just had Covid now, not only would I not have to worry about catching it in the Cusco, Lima, Mexico City, Seattle or Boise airports, I wouldn’t be contagious by the time I got to Boise. I really would have to get infected in the next week or two, so that I would for sure be recovered by February 17th, when I leave Cusco.

The probability that I would have a severe case of Covid is low. However, it’s one of those low risk, high consequence situations. It’s like wearing a seatbelt. Of the thousands of times that I’ve ridden in a car, wearing a seatbelt, I’ve only ever needed it once. That one time, it definitely saved my life. The probability of rolling an Isuzu Trooper is very low, but the consequence of not wearing a seatbelt in a rolled Isuzu Trooper is very high.

I know that it’s not really worth the risk. I need to try to be as safe as I have been the past nine months. In February, I’ll probably want to do a more serious self-isolation kind of quarantine.

For now, I’m going to be careful, but still go to two Christmas parties.

Wednesday, 23 December, 2020

There will be about ten people at Kerry’s Christmas party. She’s actually renting out an AirBnb with five bedrooms, a big rooftop with an incredible view of Cusco, and a big kitchen and dining room. My favorite part of the photos she showed me on AirBnb was the giant dining table with bench seating. It reminds me of the Frenchglen Hotel, in Oregon, which serves a Thanksgiving dinner every day, with family style serving around a giant table with bench seating.

Before the pandemic got bad, my friend Amanda managed to travel to Peru and visit me in February. She brought me a bag of Tollhouse chocolate chips. A giant bag of a whole pound, to be exact. Even though I was stress baking a lot in April and May, I stuck with apple pies. I didn’t want to waste something as special as real Tollhouse chocolate chips on myself. I wanted to make a giant batch of cookies for some occasion when there would be other Americans who would appreciate how amazing it is to have Tollhouse chocolate chip cookies in Peru.

I had hoped that by November the pandemic would be under control enough that I would be able to have a big birthday party. That didn’t happen. Then Thanksgiving was deemed too dangerous and I made an apple pie for my one guest. But Christmas, with Kerry’s party, is too good to pass up.

My oven is small and my cookie sheet is so small that I can only make six cookies at a time. The first six were strangely flat. I tried refrigerating the dough, thinking that maybe that was the problem. A dozen cookies later I called my Mom, who reminded me that I live at 11,000 feet and that even 3,000 feet of altitude is enough to require recipe modifications. I added some flour and turned up the temperature.

It took me about four hours, baking six cookies at a time, to get through all of the cookie dough - and I saved some in the freezer for topping ice cream. I’m going to keep it a surprise for Christmas. There will be three other Americans there and I know that they will appreciate how special it is to have Tollhouse chocolate chips in Peru.

Baking at altitude

The bottom cookie was made by following the recipe on the Tollhouse chocolate chip bag. The top cookie was made with additional flour and baked at a higher temperature to compensate for the altitude.

Thursday, 24 December, 2020

Yesterday was the cookies and today is the apple pie. I promised to bring dessert to Kerry’s Christmas party tomorrow partly because that’s what I’m good at and partly because this afternoon I’m going to Urubamba and I hope to be back in time for her Christmas dinner tomorrow, but transportation might be complicated on Christmas.

All Granny Smith apples in Peru are imported from Chile. There are some apple varieties that grow in Peru, but I really don’t know why Granny Smith don’t grow here. Regardless, I won’t make apple pie with any other variety, if I can help it. Last night I mixed up the pie crust, cut it in half and left the two balls of dough in the fridge overnight.

Lemons are also hard to find here. There is a sweet variety of lemon, that barely looks like lemon and currently isn’t in season. Limes are ubiquitous in Peru, but I prefer lemon juice to keep the sliced apple from turning brown before I get the pie in the oven. Just like the recipe modifications for the cookies, pie has to be cooked longer and at a higher temperature at this altitude.

After I finally got the pie out of the oven, I took a taxi to the bus stop for Urubamba. Taxis are usually s/4 but for Christmas everybody had jacked the price up to s/6. That’s still only about $1.60, so I’m not complaining. Where usually there are several vans trying to get people to go to Urubamba, today there was a line of people waiting for the next van to get back to Cusco. Apparently there are a lot more people traveling on Christmas Eve than there are people willing to drive back and forth from Urubamba.

When I finally got there, it was already getting dark and Urubamba was lit up with Christmas lights. It’s a very cute little town, with a nice green park with statues and fountains in the middle of the main plaza. The town hall had a big nativity scene set up, with baby Jesus wearing a traditional Quechua outfit, similar to the people I met on Sunday in Hatun Q’ero.

Auqui’s family also has a large nativity scene set up in an outside area that has a roof over it. There are lights around the nativity scene and their baby Jesus is much more traditional, wearing a little satin gown with lace.

At about 11:00 we had chicken and potato soup, followed by hot chocolate and panettone. Chocolatadas are not only for charity events like the Covid Relief Project. All Peruvians hold chocolatadas with friends and family, coworkers and neighbors and the hot chocolate is always made with pure cacao. With about twenty people for the chocolatada, Auqui’s sister Griselda used a one kilo brick of cacao, just like the ones we had bought for the Covid Relief Project. Just like every rural village we’ve been to, she boiled water with cloves, cinnamon sticks and the chocolate, then added milk and sugar.

After the chocolatada, we went outside to the nativity scene for some family traditions and the confetti. This is probably my favorite part of holidays in Peru. For birthdays, Christmas and New Year, you get a big handful of confetti and put a little on everybody’s head as you give them a hug and wish them Merry Christmas or Happy Birthday or Happy New Year. By the end of the hugging, everybody has a pile of confetti on top of their head. Except for holding the event outside, there were no other modifications for the pandemic. We weren’t wearing masks while we were hugging everybody in the family, even for Auqui’s father who is 83. Considering that so far nobody in the family knows anybody who has had Covid, they are clearly willing to take some calculated risks.

Peruvian nativity scene

There is no plastic made in China in a traditional Peruvian nativity scene. The decorations are natural mosses and plants gathered in the nearby cloud forest. This presents it’s own environmental challenge, but at least it’s not plastic. The most traditional baby Jesus is actually made from corn flour. Most are ceramic now, but they are still made locally. The monkey hanging upside down to the left of Jesus is a family inside joke and certainly not traditional. Under the white veil is a second baby Jesus that is usually taken out on Christmas Eve and taken to the church for mass. This year, with the pandemic, only one person from the family went to mass.

Friday, 25 December, 2020

This morning I had a traditional Christmas breakfast with Auqui’s family, which included a soup similar to our 11pm meal last night. We walked around town a bit, masked because we were in public. Urubamba currently has between 0 and 5 new cases per day, so people are pretty relaxed, even if they’re all still required to wear masks.

Around noon I left Urubamba to go back to Cusco for Kerry’s party. After a quick stop by my place for the pie and cookies, I walked up to the rented party house. It’s actually a hotel named the Blue House, just above the San Blas viewpoint. The view from the rooftop is amazing and as soon as the sun came out we all went upstairs to enjoy seeing Cusco laid out at our feet.

Sonia organized a gift exchange game, which required each person to bring three gifts. Since a roast dinner takes a very long time, we played the gift game before dinner. After the game, Kerry put my presents from Mom under the tree. Two weeks ago, when a box of presents arrived from my Mom, Kerry wrapped each one for me. It’s easier for customs if nothing in the package is wrapped, but obviously more fun for Christmas if everything is wrapped. I got six books, rose hand lotion and a Mark Twain quote on a little dish: “Forgiveness is the fragrance at the violet sheds on the heel that has crushed it.”

Kerry got up at 6am today to get the turkey in the oven, then she started on the sides: roasted carrots, crispy roast potatoes, mashed potatoes, mashed sweet potatoes, green beans, braised red cabbage in balsamic vinegar, cheesy leeks and pigs in a blanket. She had also bought a smoked ham, which barely fit on the table. It was an impressive spread, which I loved except that we all ate so much that even two hours after dinner nobody was able to eat the apple pie or cookies. They’ll make a great breakfast.

Saturday, 26 December, 2020

Despite our best intentions, there will be no chocolatada today. All week we couldn’t get anybody to answer our calls or messages. Since the Covid Relief Project is dependent on local government to provide transportation, there’s really nothing we can do about people taking vacation for Christmas. New Year will probably also be a challenge for us. I’m hoping that we will be able to get it together to do our last chocolatada on Sunday, January 3rd.

Since I unexpectedly had today off, I decided to apply for new job. Besides Hannah, who sells sweaters, all of my other expat friends in Cusco have turned to teaching English online during the pandemic. Kerry used to teach English in person and Sonia used to teach yoga in person. So, I’ve decided to join the bandwagon. After hearing all of them complain about various aspects of several different companies, I decided to go with Cambly. It’s currently Kerry’s favorite, is based in San Francisco and pays in US dollars. If I decide to work with Cambly, they’ll pay me about twice what I’ve been charging people here for in person lessons. Considering that I plan for the Covid Relief Project two wrap up in the next week or so, I should have some time soon to actually get a job.

Since this is my first Saturday in Cusco since November, I went one last time to the used clothes market Baratillo. With only s/73 ($20) I bought three large sacks of warm coats and sweaters. However many families are at this next village, the clothes we have will just have to be enough. I’m always worried that we won’t have enough clothes, although at the past five villages we have had extras that we ended up taking back to Cusco. As our last chocolatada, I am determined to bring nothing back to Cusco after this next village.

If I continue to receive donations, I’ll organize a school supplies drive and take it to one or more of the villages that I already know. The places we visited on December 5th, along with both communities I’ve seen in the Q’ero Nation will all need school supplies when school starts again in March. The 2020 school year wrapped up just before Christmas for students, although teachers here have a lot of reports and end of year paperwork to get through. We are all waiting for the government to decide if school will be in person next year, or if kids will have some sort of hybrid learn from home with a little time in school. I highly doubt that school in 2021 will look like school in 2019, but there’s still no telling what next year will bring.

Covid in Cusco: Week 40

This week I took the Covid Relief Project to two villages. We visited Japu, of the Q’ero Nation, on Sunday and Marampaqui, near Ocongate, on Saturday.

Sunday, 13 December, 2020

40 weeks is full term! Cusco has carried our Covid baby to full term, but now what? It has been a full nine months since Covid was officially diagnosed in Cusco, on March 13th. So much has happened, sometimes it feels like a full decade, not just one year. I don’t think that we’re yet at a point in the pandemic when we can actually have an idea of what the future will bring. I can really only focus on one day at a time. My biggest priority is surviving the pandemic, hopefully staying healthy until I can get a vaccine, not getting Covid at all. Anything beyond that is gravy.

However, today was so overwhelming that it’s hard for me to call it gravy. I got up at 4am to go back to the Maytaq Wasin Hotel and load the truck for the village of Japu (pronounced Hapu). The mayor of Paucartambo sent two extended cab pickups to carry us and all of the supplies for 80 families. We took supplies to make hot chocolate for 350 people, plus 350 mini-panettones. For each family we had 5 kilos of rice, 1 liter of vegetable oil, 1 kilo of salt and 2 bags of oatmeal. We also took a giant sack of 500 oranges. Considering how far away they are, I doubt they ever get fresh fruit.

Even with Dramamine in my system, I had to ask the driver to pull over a couple times so I could get out of the car and try to catch my breath. I managed not to throw up, but until the road got so rough that we had to be in 4 wheel drive, I felt so carsick. The worse the road got, the happier I was because the slower we had to go. Also, the farther we got out into the mountains, the more we saw vicuña. The four days I backpacked around Ausangate (week 37) I was disappointed to not see a single vicuña. Today I was not disappointed.

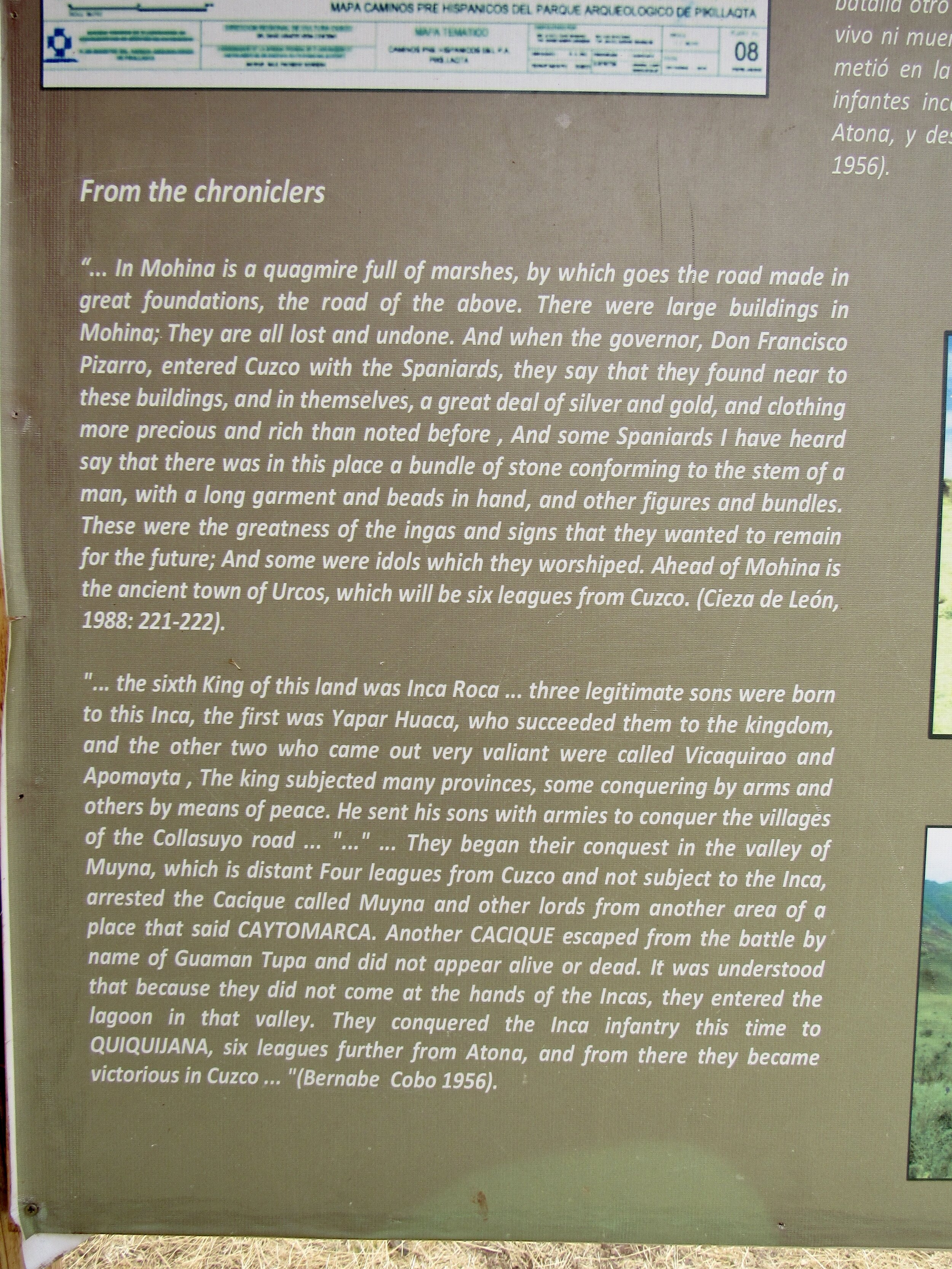

This was a trip to visit the Q’ero, who are almost mythical in Peruvian culture. They are known for their very traditional lifestyle. They did not allow any contact with the outside world until the 1990s, because they believe that they are the last descendents of the Inca and wanted to protect their culture and language from modern influences. They still live a traditional lifestyle, but since their school opened over ten years ago, the younger generation is also learning Spanish.

Of the 80 families that live in the valley of Japu, less than half of them live in the village. There is a school that opened over ten years ago, but it has been closed since the pandemic started. The teachers only came a few times all year, according to one of the fathers I asked. There is no healthcare available in Japu and the nearest government clinic is at least three hours away, in the town of Ocongate. Almost all of that time is on a very rough dirt road. The people of Japu are farmers but at their altitude of over 4,000 meters, the only crop that will grow is potatoes. They also have beautiful streams and eat trout. They shared some boiled potatoes and fried trout with us after the event. Today’s event had four stages: clothes for kids, chocolatada, food distribution and a final frenzy for oranges.

We brought clothes for all of the children, which we distributed while the hot chocolate was still being made. We had separated out a bag for babies under a year, bags for both girls and boys under five years old, bags for kids 6-10 and bags for tweens and teenagers. The clothes distribution went quickly, then we brought out two giant cauldrons of hot chocolate. We had brought with us 3 bars of pure cacao, each one weighing a kilo. We also brought cinnamon sticks, cloves and sugar for the hot chocolate. We brought a metal can straight from a dairy with 30 liters of milk in it. We made sure that they boiled the milk before we served the hot chocolate. We buy fresh milk because it's more nutritious and also it avoids all kinds of packaging waste. We were careful to take our trash out with us, since they obviously don't have any way to dispose of trash other than in their beautiful valley.

After everybody had a panettone and seconds on the hot chocolate, we asked one representative from each family to come receive 5 kilos of rice, a liter of vegetable oil for cooking, 1 kilo of salt with iodine (which is almost impossible to get up in the mountains) and two bags of oatmeal, which is fortified with vitamins and minerals for children. Malnutrition and anemia are serious problems up in the mountains.

Before we left, we gave everybody two oranges each. They were even more excited about the oranges than the hot chocolate and panettone. Several of the smaller children just ate the oranges as if they were apples, peel and all! I have no idea how often fresh fruit gets up to them, since they are at the end of a very long dirt road. The road was built only ten years ago, before which walking was the only way to get to or from Japu. People there own llamas and alpacas, but I didn't see any horses. I don't know if that would be a transportation option for a person who needed to get out for medical help. There is no regular transportation to Japu, so most people only walk. There is no cell service and they don't get any radio signals either.

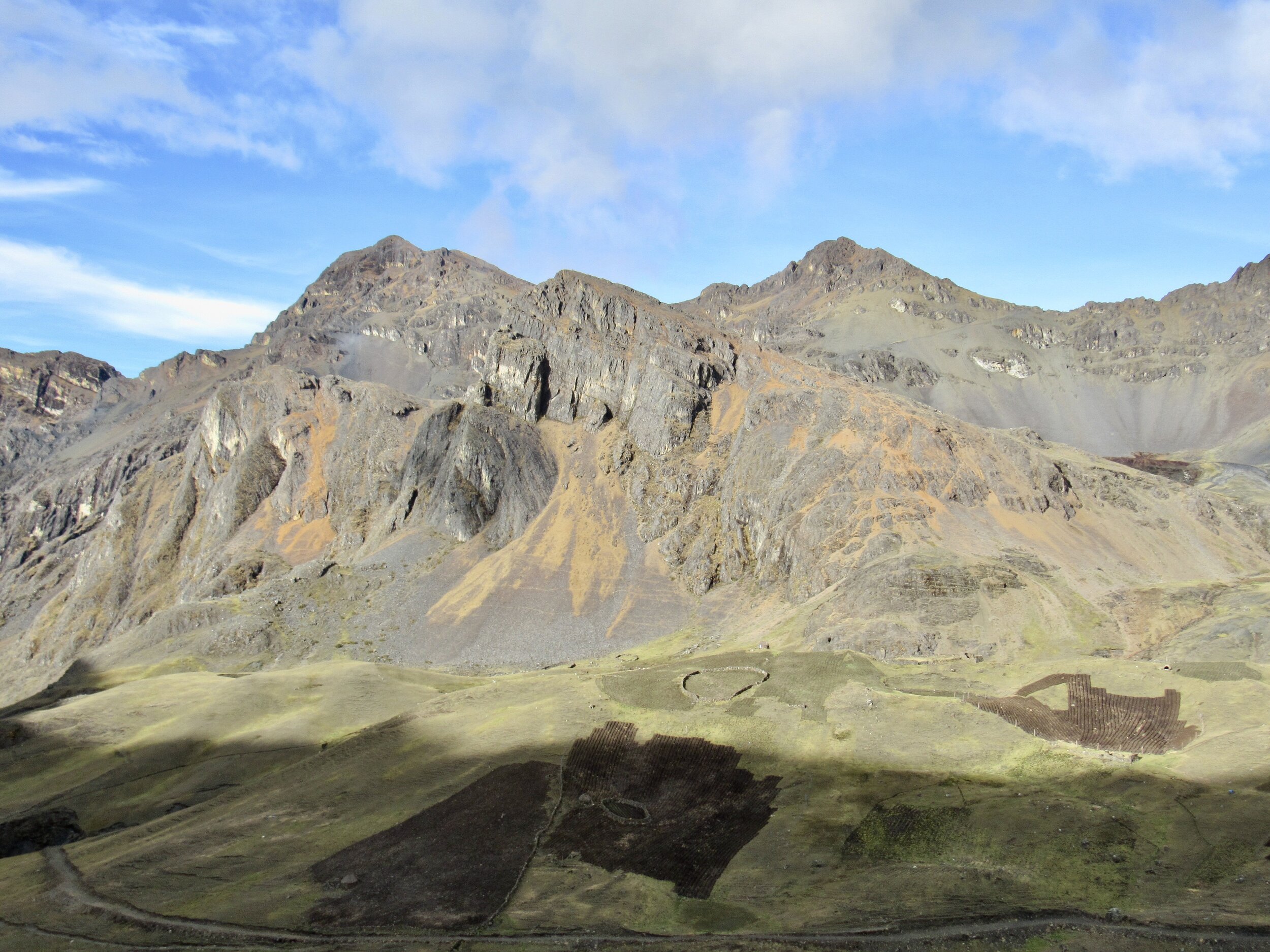

The road to Japu, six hours from Cusco and almost three hours from Ocongate, goes up and over two passes. The highest of these passes is over 5,000 meters, this is where I finally got to see vicuña, which are an endangered, wild cousin of the llama. They are quite rare and normally very skittish. Usually, you only see them off in the far distance and as soon as you stop to take a photo, they take off. They can run very quickly up steep slopes of loose scree. For there to be vicuña in the area shows that the Q’ero are really taking good care of their land. That the vicuña were so close to the road is evidence that not only do cars rarely come this way but also that poaching is not a problem in the area. Illegal hunting is a big problem in Peru because there is practically no enforcement of hunting laws. Only in very protected areas are endangered animals actually safe. Thankfully, the Q’ero still have a deep respect for and close relationship with the Pachamama.

Now, we need the government to provide education in Quechua and healthcare for each village in the Q’ero Nation, so that people can keep their language and culture, but also benefit from the services that other Peruvians are afforded in towns and cities. I hope that living conditions improve so that the children we saw in Japu are able to stay in their community and keep their language and culture alive.

We got home after 8pm and I crashed almost immediately.

Monday, 14 December, 2020

Two days in a row felt like a lot, mostly because of the long hours on roads that make me carsick. I want to sleep or just read a book all day, but we’re setting out for another community on Friday, so I need to spend today organizing for next weekend.

I went to Wagner’s, to see if he could give us 4 kilos of rice and 2 kilos of sugar for the same price that he was giving us 5 kilos of rice. The answer was no, but the difference was small enough that I went for it anyway. Yes, people need food and rice is high calorie and easy to cook in just water. Sugar is not the same kind of necessity, but as I noted back in June, sweets can be very comforting for many people. I was stress-baking a lot during the first few months of quarantine and lockdown. The only thing that stopped my increase in sugar use was that Cusco ran out of butter. I can make banana bread with oil, rather than butter, but pie crust is just so much better with butter.

I spent about two hours negotiating back and forth with Jorge, trying to get him to go down a bit more on oatmeal and sugar. Thankfully, we have had a few extra donations come in, so I actually have more to work with than I had initially planned. If this were May through August, I would be saving it for the next community. However, there are only so many weekends in December and only so many days that we can actually go somewhere. That means I’ll just get to do a better job everywhere we go.

I’m not saving for next time. I’m hoping that there won’t be a next time. I never wanted to run a non-profit and still don’t. I named this the Covid Relief Project because I wanted it to just be a stop-gap while tourism was completely dead. I wouldn’t say that tourism is back to life yet, but it’s starting to wake up a little. We have tourists from Lima, even if we don’t really have any international tourists yet. I hope that the Covid Relief Project will not be needed quite so much after Christmas.

Tuesday, 15 December, 2020

My Christmas presents arrived today! Considering how long my last package took to get here, my Mom sent my Christmas presents a month ago, hoping that they would get here in December. They actually arrived over a week before I had expected them to get here. I’m not opening them yet. I’ll actually wait for Christmas.

Kerry is planning a giant Christmas event, per the usual Kerry party extravaganza. She wants the big family Christmas so badly that she’s renting a giant AirBnb so that we can all sit together at a giant table for Christmas dinner. I’ve committed to making an apple pie and cookies but am trying to stay out of the middle of everything. She’s also planning some gift exchange game that requires everybody to bring three gifts. I suggested a white elephant gift exchange, which only requires one gift per person, but she’s set on three. She was also set on spending a crazy amount of money on a smoked turkey and smoked ham. Sonia talked her into buying a frozen turkey and roasting it ourselves, but she wouldn’t budge on the ham.

Whatever ends up on the table, I am sure that it will be an extravagant Christmas for all of us.

Wednesday, 16 December, 2020

When we backpacked around Mt. Ausangate three weeks ago, Auqui did all of the planning and organizing and guiding. Despite all of the work he put into the trip, and all of the work he did as guide every day, he told everybody that he considered this a friends’ trip and that he didn’t want tips. I think everybody was a little disappointed by that, not knowing how to thank him enough. I suggested that they buy him drinks at the hot springs or take him out for lunch or dinner when we got back to Cusco.

Today Sair, the guy we started calling General on the trip, since he was in the military in Colombia for a couple years, took Auqui and I out for ceviche. This is by far my favorite Peruvian food, and I do consider it Peruvian. Several countries in the Americas claim to be home to ceviche, but since each country does it a little differently, I think they’re all right. Peru is certainly the birthplace of the kind of ceviche that we eat here.

Peruvian ceviche is “cooked” in cold lime juice. They use tiny limes here, which are similar to key limes and have a very distinctive flavor, compared with the limes you would get at most grocery stores in the US or Europe. It’s usually topped with hot peppers, thinly sliced red onion, accompanied with slices of sweet potato and fresh corn cut off the cob.

It’s also served with “leche de tigre” which is the white, milky juice that’s leftover from cooking the fish in lime juice. It’s spicy, has a strong lime flavor and usually comes in a shot glass. That might sound kind of gross, but it’s really good. It’s more of a coastal food, but since just about anything can be flown to Cusco, we can get fresh enough fish here to make the ceviche almost as good as what you can get in Lima. I mean, now that the airports opened again, you can get just about anything in Cusco again. When the airports were closed from March 15th to August 1st, I wouldn't have eaten ceviche in Cusco, even if the restaurants had been open.

Thursday, 17 December, 2020

My Mom sent me a letter to teachers today, written by Theresa Thayer Snyder, who used to be superintendent of public schools in upstate New York. The letter is eloquent and concise, and I highly recommend reading the whole thing. She implores teachers to remember that their students “need to be given as many tools as we can provide to nurture resilience and help them adjust to a post pandemic world.”

I appreciate that she points out that “their brains did not go into hibernation during this year.” Kids have learned so much this year. They know more about what a virus is, how they travel, how contagious diseases work and how to deal with isolation than any other generation, ever. Yes, we’ve had pandemics before, but we didn’t always have the same scientific knowledge. Maybe kids haven’t been able to spend as much time focusing on math, but I bet that the amount of time that they’ve had to focus on science has more than made up for it.

I really hope that somebody doing a doctorate in education studies what it is that kids did learn this year. What did they learn about humans as social animals? What did they learn about the differences between how introverts and extroverts handled isolation? More importantly, what did they learn about themselves during this ordeal?

As much resilience as we have all needed to get through nine months of pandemic, we will need more. Yes, some countries have begun distributing a vaccine, but this pandemic is far from over. We are not really that close to a post pandemic world yet. Not that teachers shouldn’t start preparing for when we do get there. In my twelve years teaching I learned that there is no such thing as over-planning. There are an infinite number of ways that children can act and interact, with each moment requiring the teacher to think on their feet. The more scenarios you have gone through in your head and more importantly the more experience you have working with children, the better you are likely to respond to the situation.

All of us need to start thinking about how we are going to adapt to whatever the post pandemic world will look like, even if we have no idea what it will look like.

Friday, 18 December, 2020

This morning I had to run around town a bit, getting the last few things that we’ll need for the weekend. I first went to the wholesale fruit market, where I negotiated the price of a hundred oranges from s/24 down to s/22. Last week we paid s/28 for a hundred, so I shopped around at a few other vendors. I got two sacks of 400 each for tomorrow and two sacks of 300 each for Hatun Q’ero on Sunday.

I got a station wagon taxi to take everything to the Maytaq Wasin, so that later in the afternoon we could pick up the oranges and the clothes at the same time. The next errand was to the San Pedro market where I got another three kilos of pure cacao. Of the sixteen kilos that Auqi and Henry originally bought, we only had three left for Saturday and one left for Sunday. I now have two for Sunday and two more for the chocolatada that we’re doing after Christmas. There is still plenty of cinnamon and cloves from the kilo of each that the guys bought.

Then I rushed home to get my stuff ready to spend the night in Ocongate and be ready for cold and rain and sun tomorrow. We’re going to be up at the altitude where you can easily get four seasons in one day, so you really have to be ready for anything.

I walked down to Wagner’s around 4:00 to meet the truck that the mayor of Paucartambo sent to take us and all of the food to Ocongate tonight. It was another four hours of twisty mountain roads. We got there well after 9:00, just in time for a very late dinner, then we were taken to a hostel where all of us crashed almost immediately.

Saturday, 19 December, 2020

We got up at 5:30 and first went to the market for coca leaves and sugar. Yesterday in our rush to get out of town I forgot the sugar back at the hotel. At least we got all of the food and clothes and the rest of the hot chocolate supplies. The coca leaves are for the elderly people who come to the chocolatada. We have clothes for the kids and 4 kilos of rice and 2 kilos of sugar for the adults. I’ve felt like we’ve left out the village elders a bit in the past, so this time we made sure to have a little something for them too.

Coca leaves are chewed and give you the same effect as a cup of coffee and an ibuprofen. They’re great for headaches, or any kind of aches for that matter. Hence, their popularity with the elderly. They can also be used to make cocaine, but it takes about 600 kilos of leaves to make one kilo of “cocaine base,” according to Recovery.org. In my experience, the leaves themselves are much less addictive than coffee.

Coca leaves are also very sacred in all Andean traditions, despite the fact that they’re from the Amazon jungle, not the Andes. However, the harsh life in the Andes, especially living at high altitude, often requires medical assistance of some sort. The oldest medicine in South America is coca leaves and they have taken on special cultural significance because of what seems to be magical powers.

Today went pretty similarly to the previous three chocolatadas. We made sure that the women making the hot chocolate got the chocolate, milk, sugar, cloves & cinnamon. Then we handed out clothes to the kids. Then we had the chocolatada, making sure that everybody got a panettone and at least one cup or bowl of hot chocolate. Lots of kids had forgotten to bring a cup and lived too far away to go home. They either borrowed somebody else’s cup or found a water bottle or something that could hold liquid. We did our best to be sure that everybody got hot chocolate and I hope nobody got left out. I’m really bad at estimating how many people were there, but I would guess at least four hundred.

After the chocolatada, we gave out the oranges, rice and sugar, along with some leftover panettone. Unfortunately, Saturday is also market day in Ocongate, so there were quite a few adults missing from Marampaqui. The mayor of Ocongate was a huge help with calling out kids to represent their family and receive the donations. We really rely on local leaders to know who is in which family and keep track of who has already received their donations. By the end of it, there were still 16 families missing, so we entrusted their donations to the community president.

The community served us a big tub of boiled potatoes and little pats of soft, fresh cheese. It’s always interesting to see what a community wants to share, or more like, what they have to share. This is the first time I’ve been given cheese and it was delicious. Cheese here is not cured with rennet. It’s more like fresh cheese curds. They add vinegar or lemon juice to the milk until it curdles, then squeeze out the extra liquid. Depending on how it’s made, it can be a lot like Indian paneer. After our snack/lunch, we all piled into one car and hit the road.

We got back to Cusco by 5:00 and headed straight to the Maytaq Wasin. Wagner’s delivered the food for tomorrow, which is more than we were able to give to Marampaqui because it’s a smaller community. We still have 4 kilos of rice and 2 kilos of sugar, plus a kilo of salt and two bags of oatmeal. I headed home after we had all of that stacked at the hotel, but Auqui, Henry and Sair kept going. The truck from tomorrow’s community, Hatun Q’ero, had already arrived at Henry’s sister’s school because they were donating desks, which they have to load before the food and clothes.

Tomorrow we are leaving at 5am for a 5 hour drive to Hatun Q’ero. It is going to be a very long day.

Read more about Japu on this blog!

Covid in Cusco: Week 39

I recover from the travel to our first chocolatada and get ready for another five more!

Our first chocolatada!

It was so heartwarming to see people enjoy a giant cauldron of hot chocolate and to see their smiles when we gave them the panettone.

Sunday, 6 December, 2020

Yesterday was amazing, but I am so exhausted by all of the travel. The farther out the villages are, the more they need help, so I’m bracing myself for a December full of twisty mountain roads that make me carsick. It’s certainly worth a little discomfort on my part to be able to reach families who need so much.

Not only are the communities farthest from Cusco lacking in basic communication and medical care, they also don’t have any way to get to a town where they could buy basic necessities or try to get medical care. The pandemic is far from over and I am always impressed when we go somewhere that doesn’t have any Covid cases in the area. They really are staying isolated and I really want them to keep staying isolated.

Faced with so much need, I tend to feel overwhelmed. It’s helpful to have my friends with me, and Auqui’s constant reminder that “algo es algo.” My Mom also sent me a quote from RBG that helps: “To make life a little better for people less fortunate than you, that’s what I think a meaningful life is. One lives not just for oneself but for one’s community.” Mom pointed out that RBG had said “a little better,” which I need to remind myself is not “totally fair and equal for everybody.”

I can definitely make life a little better for some of the families that we’re visiting. That seems like a realistic goal for me. As with anytime I’ve got a cause I’m working for, I get frustrated when other people don’t think that it’s as important as I do. Several times, we have run into roadblocks of one form or another from local government hacks who can’t be bothered to call us back or organize transportation for us. I am dependent on local mayor’s offices to pick us and the donations up in Cusco, take us to the village and then get us back home at the end of the day.

Even yesterday’s event didn’t get much support from the Calca mayor’s office. They guy who worked with us, Elio Huaman, didn’t get the help he needed from his bosses, but he made it happen anyway. I am so thankful that among the useless people in every administration there are often people like Elio who have their heart in the right place and will do whatever they can to get help to those most in need.

The children of Airepampa

I just couldn’t get the image of those cold little feet out of my mind.

Monday, 7 December, 2020

After taking yesterday off, today I’m working on the video of last Saturday’s event. I’ve gotten a little better at these over the past few months, but it’s still a laborious process for me. The first step is to listen to the interviews and speeches over and over, transcribing and translating simultaneously. Then, after I get all of the clips edited together how I want them, I put subtitles in English for everything that’s in Spanish and Quechua. I can’t translate Quechua by myself, but that’s where Auqui comes in. I really couldn’t do any of this without him and Henry.

Today, watching the clip where Elio speaks to the people of Airepampa, the kids running around just about break my heart. Sometimes, there are images that just stick with us, that really pull at our heartstrings. What’s really getting to me right now are their cold little feet. The kids I saw on Saturday were wearing one or two pairs of pants or leggings, at least two skirts and three or four little sweaters layered on top of each other - but sandals on their little feet. It was cold and the kids didn’t have any real shoes. Everybody had the same black rubber sandals that offer very little protection and absolutely no warmth. They’re called ojota and cost less than $3.

I think that what was harder about last Saturday, compared to the villages we visited May through August, was that this is much more focused on children. Before, we wanted one adult representative from each family to come to the meeting point and take home the bags of rice, oatmeal, sugar or whatever we had to give. In August we also tried buying school supplies for kids, but the kids were not the main focus of the event.

Now that I’m taking hot chocolate, sweet bread and children’s clothes, the kids are front and center. They are so cute and look so surprised to see people who look like me. I’ve had kids here tell me, after they got to know me and felt more comfortable with me, that they assumed at first that my hair must be a wig. Once they realized that it’s not a wig, they decided I must have it dyed because any color besides black or brown just isn’t natural. And those are kids who live in town. I wonder what these kids, who live so high in the mountains that they don’t even have cell service or radio, think when they see me.

Tuesday, 8 December 2020

The video isn’t done yet, but it’s still time to start planning for this weekend. We’ll be going out both Saturday and Sunday, so I went to buy motion sickness pills today. Saturday it will be about three hours of twisty mountain roads, each way. Sunday will be even farther.

Today I went to see Jorge, the wholesaler that I’ve been working with. I paid off what we had ordered for this weekend: 5 kilos of rice and a liter of vegetable oil for every family, plus bags of oatmeal and a package of crackers for each of the 90 children at the Paruro elementary school. On Saturday, while Auqui, Sonia, David, Andrea (from the Maytaq Wasin Hotel) and I are taking a chocolatada to the village of Mayubamba, Henry is going to take a chocolatada to the Paruro elementary school.

Henry’s uncle teaches there and asked Henry if he could take something to the kids there. I prefer to take what we have to families who live far from towns, families who don’t have any way to buy necessities or find work without leaving their mountaintops. Obviously, these are the families who should stay up in the mountains to avoid catching Covid. Paruro is a real town with government offices that have jobs programs, hiring as many people as they can to do everything from paint crosswalks to pulling weeds in parks. Paruro also has shops where people can actually buy things.

Still, Henry pointed out to me that everybody is in need this year. I can’t argue with that. We do have enough in the budget for him to take a chocolatada and oatmeal to 90 kids, so why not? We do have some donations still coming in, so I don’t think it will take away from what we were going to take to the other villages anyway.

Wrapped up in my do-good world of the Covid Relief Project, I was shocked to hear that in Boise, where my parents live, the Anne Frank memorial was vandalized with swastikas. Why do people want to spread hatred? Why is it so hard for some people to embrace or even just accept, people who are different from them? How could somebody put a swastika on Anne Frank’s statue? She was just a kid! She probably had cold little feet when she was in the concentration camp.

Wednesday, 9 December 2020

I’ve never been much for Christmas movies, Christmas music, much less Christmas shopping. Still, when I was a kid my parents used to take me to a big family gathering at the Belts’ house on Christmas Eve. Every year, the highlight of Christmas Eve was the book The Polar Express. When I was little, I listened to somebody read it to all the kids. The year that I got to read it to the little kids, I felt like I was growing up. It meant a lot more than a quinceañera or a sweet sixteen party.

So, when Kerry invited me to watch the movie Polar Express with her and Sonia tonight, I was really excited. This is the sign that Christmas is coming. It may be too warm here to feel like Christmas, but Sonia pointed out that it’s raining here as much as it usually does in England on Christmas.

It’s a funny thing to be in the southern hemisphere for Christmas. In North America and Europe we’re so used to Christmas being about hot drinks and snow and evergreen trees and snuggling up in front of a fireplace. We do have hot drinks here, but not more than usual. At altitude, you get cold and dehydrated quickly, so drinking endless cups of tea and hot chocolate are normal all year.

I’ve celebrated Christmas in several warm countries: Mexico, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Peru and even on the beach in Cartagena, Colombia. One year, I thought I was going to be in a warm country, only to discover that Hanoi, Vietnam, is really cold in December. I had to buy a fake North Face down jacket, since that was the warmest option available. I had to buy XXL, which makes it obvious that they are not made for export. Those are Vietnamese sizes. I loved that the logo had been modified to read The North FFace.

Thursday, 10 December 2020

The rains have set in for real now. Our first day of real rain was December 1st, which is over two months late. The dry October and November killed most of the crops that people planted in August and September, since so few people here have access to irrigation systems. I am so relieved for the rains to finally be here, knowing that not only will the farmers be happy but that also I won’t see anymore wildfires. Wildfire season is definitely over.

The national news picked up Boise’s tragedy from Tuesday. NPR quoted Boise Mayor Lauren McLean “Bad actors who use racist and violent rhetoric are not welcome in this community.” I hope that Boise manages to turn this around. It is starting to become a more liberal community, with a growing population of refugees. They really can’t let this kind of hatred take hold.

Wholesale fruit market

This is where we got over 500 oranges for less than $40 USD. Where we’re going Sunday is so high up in the mountains that I bet they almost never get fresh fruit.

Friday, 11 December 2020

I am always happy when I can negotiate prices down and convince those who are selling food or children’s clothes to give me extra discounts because what I’m buying is going to be gifted to families in need. We already have everything set for tomorrow, but I still have a little money from the budget for Sunday. Auqui and I took it to a wholesale fruit market and bought a giant sack of over 500 oranges.

The woman selling actually tried to talk me into the cheapest oranges, when we asked her to give us a discount for both buying in bulk and buying to donate to families in need. I tried to politely thank her for her advice, but also told her that just because they’re poor, they shouldn’t have to always get the cheapest option. Already we’re taking them used clothes, which are all in good shape, but still used. This is Christmas. I want to give them the nicest things that we can afford, and we can afford the most expensive Valencia oranges, so that’s what we bought.

We took the sack of oranges to the Maytaq Wasin Hotel, where we met my friend Sarah. She was there to help us sort through the clothes. We dumped out the bags that we had bought two weeks ago and sorted them into baby clothes, little kid clothes and big kid clothes. Peruvian culture is very heteronormative, so we sorted out little girl clothes from little boy clothes. For both Saturday and Sunday, we put together five bags of clothes: baby, girls 3-10, boys 3-10, girls over ten years old and boys over ten years old. It’s a rough estimate on sizes, although some of the clothes helpfully say on the tag what age they’re for.

Wagner was supposed to deliver the rest of the rice, oil and oatmeal at noon, but it didn’t arrive until almost 4pm. I was getting hangry by then and was so glad to leave for lunch, before going home to pack for tomorrow. All of today was taken up with preparing for the weekend chocolatadas. It’s a good thing I’m not trying to juggle a fulltime job with all of this!

Saturday, 12 December 2020

Today was our second chocolatada and we met at the Maytaq Wasin Hotel at 5:30, to try to get the truck loaded and hit the road as early as possible. Today’s drive was only about three hours, but since we’re also going to another village tomorrow, I want to get home early in the afternoon so I have time to catch my breath before it’s back on those mountain roads.

Henry got there right at 6am, with two milk cans that each hold 30 liters, and 350 mini-panettones. We dropped him off with one of the milk cans and 100 of the panettones at the elementary school in Paruro, then kept going to Mayubamba.

Just like last Saturday, they already had a big cauldron of water boiling, ready for the chocolatada. When they saw the 30 liter milkcan, they ran to get a couple more pots, to take out some of the water so there was room to add the milk. It’s fresh milk, so they had to make sure to boil it before it could be served. We added three of the 1 kilo bricks of cacao, a bag of sugar, a handful of cloves and a stick of cinnamon the size of my arm. I don’t know why it seems so cool, but I just love these giant cinnamon sticks.

All of the kids from the village were already there, so we lined them up, smallest to biggest to start giving out the clothes. It was pretty cute to see kids choose their favorite of the options available. It’s not always easy to judge the right size, but if the kid picks it out, I’m sure they’ll make it fit. After clothes was hot chocolate and panettone for everybody. After everybody had seconds on hot chocolate, we asked an adult representative from each household to line up for the rest of the donations.

The rice and oil seem pretty standard to me by now, so I was really happy to see the packs that Andrea had put together. From her hotel Maytaq Wasin, she donated six towels for each family. She has also been collecting donations, so she was also able to buy five bars of soap, four toothbrushes and toothpaste for each family. Hygiene is a real challenge when you live in an adobe home without plumbing and any help is appreciated. Andrea even included toothpaste for kids. Also, toothbrushes and toothpaste are not high on the priority list for families that are really struggling to get by. Few shops carry them and they’re just prohibitively expensive for most of the people of Mayubamba.

After we had handed out the food and packs from the hotel, we gave out some toys that David had collected from his students. Finally, we handed out the last of the panettones to anybody who had stuck around. It was a lot more than the village leaders were expecting and they were so happy. Before we left, the community president invited all of us for lunch, which was served in an empty classroom in the closed school.

Most communities are only able to share boiled corn or potatoes, which I am perfectly happy with! However, the mayor of Paruro had sent supplies to make chicken and potato soup with his assistants. He wasn’t able to be there today, but he certainly sent enough people to support us, including local police. It was cute to see the police helping the littlest kids who were having trouble carrying a mug of hot chocolate and the panettone and a granola bar, donated by the Maytaq Wasin.

The mayor also sent scarves and bags for those of us who came from Cusco. They’re from the Paruro artisans cooperative and are obviously made for the Cusco tourist souvenir market. Sadly, they have been sitting around for almost a year, since no tourists have been here to buy souvenirs. Tourism is starting to come back and I hope that the economy will revive. It’s starting very slowly, mostly with tourists from Lima. It may be several more months before people are able to travel from the US and Europe, where most of our tourists come from.

We got back early enough that I had time to go over the budget for tomorrow again. I had a little money left over, so I went back to Wagner’s and bought two bags of oatmeal and a bag of salt for each family tomorrow. Oatmeal is actually considered a treat here and it’s surprisingly hard for some families to get salt. You can’t cook without salt and in communities that don’t have any shops, it can be a long trek to buy some. Considering how much we had for Mayubamba today, I don’t want to feel like we’re taking less to Q’ero tomorrow.

I’m really excited to see Q’ero, which I have heard so much about. It’s famous here in Cusco as the last holdout of pure Inca culture, who only started to allow outsiders to visit them in the 90s. Before then, they had stayed isolated, refusing all contact with the outside world. According to Auqui, the first people who left Q’ero were not allowed to return. The community was that determined to keep their culture and language from outside influence. I’m excited to meet them and see how much outside influence has changed them in the past 20 or so years. I also wonder what they think about the pandemic. Will they see it as a justification to seal themselves off again?

I’m also interested in their take on climate change. The Q’ero are known for both their ancestral knowledge of stories passed down through the generations, as well as their close connection to nature. I’m very curious what changes they have noticed in the past few decades, compared with what they know of their land over the past several centuries. I expect that they have a unique perspective that will be very insightful.

Old fashioned milk can

I think it’s so cool that we can buy milk directly from the dairy and that they’ll let us borrow the milk cans.

Covid in Cusco: Week 38

I took the Covid Relief Project’s first chocolatada to families who live high in the mountains, about two hours north of the town of Calca. It was a beautiful and very impactful day.

Sunday, 29 November, 2020

I’m still so happy about last week’s trek around Mt. Ausangate! The mountains here are one of the biggest reasons that I wanted to move to Cusco. It’s really amazing to see how different the climate here is, depending on the altitude. When you get down below the altitude of Cusco, you realize that you’re really close to the equator. Even just going to Machu Picchu, which is only about three hours away, takes you into the cloud forest and the very edge of the Amazon rainforest.

When you head up into the mountains higher than Cusco, you are immediately in the high altitude ecosystem, where all plants are tiny and very few trees or crops can grow. I’ve always wondered why, and finally took the time to look it up. Part of the reason is that the air, which has less oxygen for us, also has less carbon dioxide for plants. They struggle to live for the same reason that we struggle to breathe: the air is just too thin.

My aunt sent me an article from yesterday’s Seattle Times about the effect of the pandemic on farmers in Peru. The farmers interviewed are in Pisac, which is only about an hour north of Cusco. The town of Pisac itself has suffered from the death of tourism, although lots of the expats who live in Cusco moved to Pisac to escape the high Covid case numbers in Cusco. Several people I know who moved there also said that the police are less strict in Pisac and that it’s easier for them to go for hikes in the surrounding hills.

The article says that part of what is hurting farmers is that prices for crops have dropped, leaving them with less income and sometimes unable to sell what they farmed. As I’ve learned through working on the Covid Relief Project, part of the reason for this is the disappearance of tourists. Normally, Cusco and the Sacred Valley welcome thousands of tourists every day. We used to have a steady stream of flights landing in Cusco, bringing people to fill the hotels, and more importantly for the farmers, the restaurants.

Restaurants in the Cusco region rely on local produce, which not only makes the food better, it supports thousands of families who farm small plots of land. Most of these plots are fields smaller than a city block. Peru’s Agrarian Reform of 1969 broke up the big landowners, most of whom had inherited their estates as descendents of Spanish families granted the land during colonization. The system had perpetuated a kind of serfdom that bordered on slavery, which I can still hardly believe lasted through the 1960s. One result of the Agrarian Reform is that the families who farmed and lived on the land actually became the landowners.

I met families who rely on farming near Pisac on July 11th, as one of the Covid Relief Project village visits to deliver emergency food assistance. We visited two small communities and at one got to hear from a community member who talked about how forgotten these families feel. He said that they work so hard to provide food for Peruvians, but that they don’t get any attention from the government. They don’t have a health clinic and their school hardly gets any funding. Unfortunately, this is the case of every community that I’ve gone to since we started the project.

Like most countries around the world, the poorest people in Peru are hit the hardest by the economic collapse caused by the pandemic. The World Bank estimates that the pandemic will push 49 million people into extreme poverty in 2020. It’s easy to feel helpless in the face of numbers like that, but I hope that what little I can do for rural families in the Cusco region does make a difference for them.

Monday, 30 November, 2020

After Black Friday, today is another day devoted in part to the celebration of corporate America: Cyber Monday. Of course, since both of these days are related to the Thanksgiving holiday weekend, they’re not really a thing outside of the US. However, I’ve been thinking of visiting my parents for my Dad’s birthday in February, which means that I’ve been shopping for plane tickets online.

Taking advantage of some Cyber Monday deals, I managed to buy flights from Cusco all the way to Boise and back for only about $600. In 2019, that was the price of the cheapest one way tickets. The pandemic’s effect on the airlines, while tragic for many of their employees, is definitely a big help for me.

I haven’t been back to the US since I left to move to Cusco, in August 2019. By the time I make it to Boise for Dad’s birthday, that will have been a year and a half in Peru. I’ve been away longer, when I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Morocco 2005-2007, but since then have gone back every year, even when I was living in Turkey and Bangladesh.

I suspect that seeing Seattle and Boise during the pandemic will be a bit of a shock. Currently, the US is starting to see the effect of people gathering for Thanksgiving last week and the huge spike in Covid cases is predicted to get even worse in the coming weeks. I think that everybody expected there to be a spike in cases as a result of people trying to have a normal Thanksgiving. I bet that the consequences of Christmas and New Year will be similar.