Moray & Maras

So little has been studied and so much has been assumed about Moray that we got it very, very wrong.

Moray and Maras are two of the most misunderstood places in Peru.

I’ve gotten it wrong since I first visited in 2013 and was told Moray was the Inca’s greenhouse and agricultural laboratory. After 12 years repeating the same mistakes, I finally visited with a geologist and an archeologist who gave me the facts – keep reading to find out the truth about Moray and how Maras is related.

If anybody tells you that Moray was made by aliens, feel free to roll your eyes with me.

Did aliens build Moray?

Short answer: no. Moray has classic Incan stonework and clearly follows the pattern of a lot of Andean engineering masterpieces: Incan and pre-Incan cultures used some of the Andes’ most impressive geologic features to create fantastical constructions. Two of the most spectacular, built on narrow ridges above beautiful rivers, are Machu Picchu and Waqra Pukará. Another engineering marvel is Tipón, closer to Cusco.

Everything about Moray makes sense if you understand the geology of this part of the Andes Mountains.

Yet, Moray is also truly unique.

It’s the only circular depression that the Inca built down into. Most Andean constructions focus on hilltops and ridges. Incan trails rarely dip down into steep river valleys, preferring to keep to the high passes that make most of us gasp for breath.

If you visit during the rainy season, it seems plausible that they could have planted something at Moray.

What was Moray for?

Anthropologist John Earls didn’t think aliens had made Moray, but he was from Australia and clearly didn’t think like an Andean engineer or farmer would think. He spent a lot of time at Moray in the 1970s and 1980s and came up with the famous theory that it was an agricultural laboratory, used by the Inca to study and hybridize crops and perhaps acclimate crops up temperature gradients.

He found that each terrace in Moray was about one degree Celsius off the next and theorized that plants from warm climates, like the Peruvian rainforest, could be first planted in the lowest terraces, where it’s warmer, and then slowly planted up at higher terraces as they hybridized plants to acclimate to the colder climate of the high Andes.

There are several depressions filled with terraces at Moray and all have been completely or partially restored.

Does the Moray temperature theory stand the test of night?

It doesn’t sound too farfetched, until you measure the temperature of the terraces at night, which Earls apparently never did. The lowest terraces are the coldest at night, as cold air settles in the bottom. Unfortunately, it appears he didn’t ask Andeans who lived in the area if they ever used the terraces. They probably would have told him that in the winter, which is the dry season, cold but sunny, they freeze-dry potatoes by spreading them out on the bottom terraces. The cold freezes them at night and then the sun dries off any moisture during the day.

The theory falls apart if you try to picture how anybody could keep jungle plants alive on the bottom terraces, since Andean farmers didn’t have the technology to keep them warm at night.

The little clump of trees is the only spring in the area, and only one of the terraces was designed with a canal to carry that water.

Does the Moray agriculture theory hold water?

The 1980s theory that Earls coined fell apart further with the 2011 publication of Moray: Inca Engineering Mystery which showed, using a comprehensive hydrological study, that even 500 years ago, there was simply not enough water to plant crops on all the terraces. There is one small spring, which was channeled into one small canal that went to one part of the terraces. Today that water is channeled farther downhill to the bathrooms.

Yet, today most tour guides still repeat the thoroughly disproven 1980s theory.

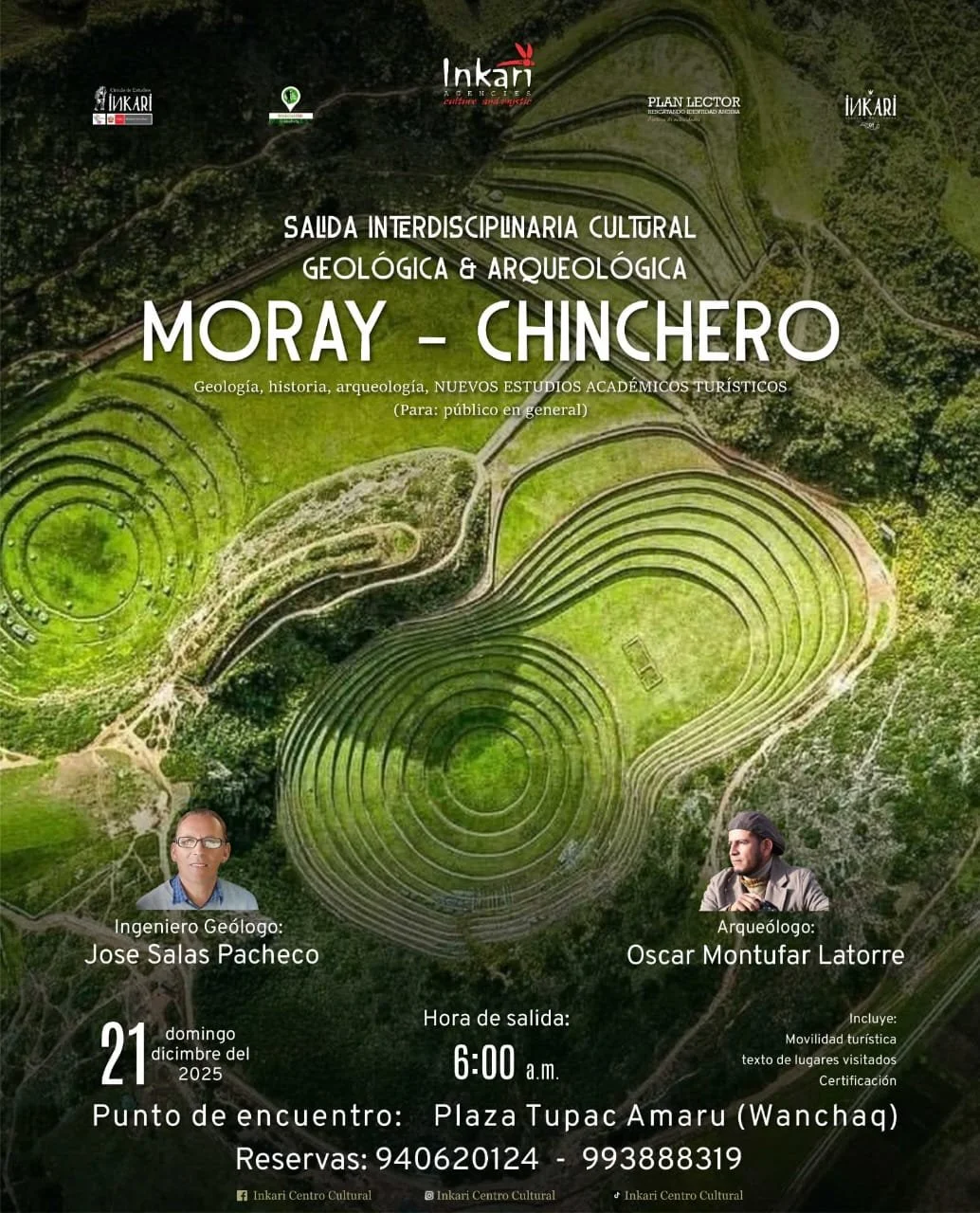

When I visited Moray on summer solstice, December 21, 2025, with a geologist and an archeologist, I overheard most guides telling tourists that Moray was an agricultural laboratory.

Take it from the experts

Professional development for tour guides is available and we have the Inkari Cultural Center to thank for bringing experts together to teach tour guides real facts. See their next events on the Inkari IG.

Why do guides repeat things that are demonstrably untrue? Why do they still use theories that have been thoroughly disproven for more than ten years?

Well, to start, not everybody gets to visit Moray with a geologist and an archeologist. The 2011 book about the engineering of Moray is not readily available in Cusco. Most guides who have learned a lot about archeology, geology, engineering and anthropology have moved on to bigger tours than the short (and cheap) Moray & Maras circuit. There are so many reasons, but none of them are good excuses.

The rectangle on the widest terrace matches residential structures for shamans in isolated places. The zig zags are stairs to get down to the lower terraces.

What was Moray really for?

According to Archeologist Óscar Montúfar (who I have worked with before and quoted in my article about Waqra Pukará), it was purely ceremonial. The rectangular structure resembles the sort of building a shaman would have lived in and there are no other residential structures in the area.

I think the misunderstanding comes from trying to understand Moray in isolation, rather than as part of the fascinating geology of the Andes Mountains.

The agricultural theory already fell apart without water but if the terraces were farmed in any meaningful way, they would have had to be tended every day. Weeds and insects were dealt with by hand, not by crop dusters. Especially if it were a well-tended “laboratory” a lot of people would have had to live close by. There are no nearby signs of any nearby villages from Incan or pre-Incan times. This was an isolated site that likely had one shaman who lived there alone. Of course, it would have taken a lot of people to build but unfortunately archeologists have not been able to access the site enough to do further studies to learn more about the construction process.

If you understand how the Andes were created, and what layers of rock are underneath the Sacred Valley, it all makes sense.

Did the Inca dig the giant holes in the ground at Moray?

Short answer: no. According to Geologist José Salas Pacheco, the sink holes around the Moray archeological site are natural. They were made when water underground was forced up to the surface and took with it minerals that it dissolved from a layer of sediment from the Mesozoic Era, which left caverns, which eventually collapsed, resulting in massive sinkholes on the surface. Water doesn’t collect in the bottom because the layer of rock below them is highly porous. (That is the most simplified, succinct version I can do of his two-hour lecture, which included the geologic layers under all parts of the Sacred Valley going back to the Paleozoic Era).

There are several natural sink holes around Moray that were not lined with terraces or used by the Inca.

Maras is squarely on the tourist trail, though it’s not an archeological site. The salt ponds are owned by the Maras community, which charges an entrance fee separate from the Boleto Turístico that covers archeological sites.

What does any of this have to do with Maras?

Most tours include Moray and Maras together, as a logistical convenience, since they’re relatively close together. What few guides will tell you is that what we see at Moray today is the result of an ancient geologic process which is still happening at Maras.

The Maras Salineras are small terraces, which make up around 4,000 small ponds. (It’s often translated in English as salt “mines” but they’re ponds, not mines). For well over a thousand years, Andeans have channeled a salty spring with water about 11ºC to alternately fill each pond, after which it is left until the sun evaporates off the water, leaving a layer of salt. That salt is scraped up and sold. It’s the most common salt available in Cusco and what I use to cook every day.

According to Geologist José Salas Pacheco, water 11º Celcius comes from around 1,100 meters underground and since it’s so salty, it’s obviously passing through layers of sediment (the ones from the Mesozoic Era) that are high in salt. It’s removing minerals underground and bringing them to the surface, which will eventually leave a massive cavern about a kilometer underground.

When it collapses, another sinkhole will be formed, just like the ones Andeans terraced to make Moray.